Category Archives: Video

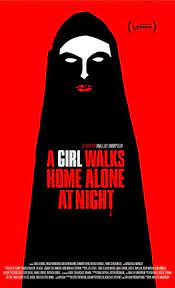

Saturday Matinee: A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night

By Jonathan Romney

Source: Film Comment

A term beloved of French film critics—and one I never tire of borrowing, just because it pinpoints its referent so well—is OVNI, meaning “UFO.” It’s used to refer to a film, usually a first feature, that’s next to impossible to categorize, that seems to have come out of nowhere, to have been made entirely against the odds—a film that appears to originate if not actually from other planets, then from some parallel cinematic dimension where the usual rules don’t apply.

Little could qualify more for OVNI-dom than an “Iranian vampire Western,” as Ana Lily Amirpour’s first feature has been dubbed. In fact, the skewed quality of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is accentuated by the fact that it both is and isn’t “really” Iranian. That is, the film is in Farsi, and stars a cast of Iranian or Iranian-American actors, but was shot in California, not far from Bakersfield, where writer-director Ana Lily Amirpour grew up. Taft stands in for Bad City, as the subtitles call it—or “Shahr Bad,” which may possibly be a Farsi play on words—a run-down, isolated burg where weird things happen by night, and nothing too ordinary takes place by day.

The Girl of the title (Sheila Vand) is a gamine-ish music fan who likes to dance alone in her poster-decorated den. But when she steps out onto the streets, she’s not the imperiled victim that the title—misleadingly, cleverly—would have you expect. She’s a figure of menace: a marauder who wears a chador over a very Gallic stripy matelot top, adding a curious dash of indie-kid chic to her image as a ghost figure who glides rather than walk. In fact, her gliding gait comes from the fact that she’s commandeered a terrified child’s skateboard. Spreading her robe like black wings, the Girl haunts the night like an Islamic descendant of Musidora’s Irma Vep, lawless masked heroine of Louis Feuillade’s silent serial Les Vampires.

The Girl is indeed a vampire, and more than a match for supposedly the scariest presence on this city’s mean streets—thuggish drug dealer Saeed (Dominic Rains), who has “SEX” tattooed across his neck, a sleazy drooping moustache on his chops, and a pad filled with big-bad-hunter tat (deer’s heads, tiger-print throws…). The predatory Saeed practically licks his chops at the thought of feral sex when the Girl’s canines pop out to full length with an almost comical sound effect; he doesn’t look so happy once she snaps his finger off.

The Girl can be downright terrifying: the young boy who loses his skateboard probably hasn’t done anything to merit being chilled to the bone by her, when she leans in to ask him if he’s been good, then warns him (in one of the most authentically ghoulish horror-movie rasps since Mercedes McCambridge did voice duty for Linda Blair), “I can take your eyes out of your skull and give them to the dogs to eat.” We don’t, by the way, see the dogs of Bad City, but the local cat is unsettling enough: a naturally charismatic starer which looks like it’s taking a break from sitting in a Bond villain’s lap, and which gets the best close-up in the film.

Meanwhile in Bad City, a devilishly handsome young man named Arash (Arash Marandi) is coping with the depressed excesses of his overweight junkie dad Hossein (Marshall Manesh), and working as gardener and handyman to a rich family whose spoiled daughter, the recent recipient of a nose job, sees him as her latest toy.

Things take an overtly comic turn when Arash—something of a sweet-natured dork despite his quiffed rebel demeanor—attends a Halloween party as Dracula. Walking home the worse for wear in a too-baggy cape and really ill-fitting fangs, he meets the Girl, who “lures” him to her den—or rather, wheels her decidedly floppy prospective beau back to her place on the skateboard. Things turn romantic, at once chastely and very sensually, in a beautiful extended take, as Arash approaches her and she closes in—not, as you’d expect, on his neck, but on his chest. It all happens in swoony slow motion, but with a mirror ball spinning round and filling the room with sparkles at crazy speed: a magnificent, and inexplicably romantic, paradox of pacing that adds to the eerie romance of the scene.

The couple later tryst at dead of night at the local power plant, itself lit up like a jeweled city. Why at the power plant? For the chiaroscuro, of course—that seems to be what motivates Amirpour most. This is one of those films that are shot in black and white because a director is genuinely in love with the affective and expressive possibilities of that visual choice, and especially with its ability to draw magic out of night scenes: I’m reminded of another piece of black-and-white small-town dream romance, Eric Mendelsohn’s Judy Berlin (99), which used an eclipse as the narrative excuse for its midsummer night’s encounters. In her own nightscapes, Amirpour doesn’t mess around with half-measures: DP Lyle Vincent saturates his shadows with the inkiest of blackness (as does the graphic novel that Amirpour has created to accompany the film).

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is a wayward, genuinely oneiric creation—look at its sudden arresting focus-pull on some oil derricks, and its graceful, gratuitous interlude of a transgender cowgirl figure dancing with a helium balloon. It manages to be tender, chilly, comic, and willfully bizarre all at once, but never has you wishing it would choose one register and stick to it. In his very enthusiastic recent review, David Thomson invokes not only David Lynch, but Vigo, Cocteau, and Buñuel, no less. Perhaps more modestly, A Girl Walks reminded me most of early Jarmusch, and of the general spirit of late-Seventies/early-Eighties punk-influenced U.S. cinema (names like Scott B and Beth B, Amos Poe, Slava Tsukerman of Liquid Sky), because of Amirpour’s brisk disregard for genre norms, for the sense that she’s up for telling whatever story she wants to tell, any way she wants to tell it. While manifestly very polished and composed, the film nevertheless gives the impression that it’s making itself up—or dreaming itself into being—as it goes along.

There’s an oddly innocent blazing-youth romanticism about it, especially when the Girl and Arash bond over music. That feeling comes across all the more strongly because non-Farsi speakers will depend on the subtitles: it adds a tender but absurd irony to the revelation that the last song the Girl listened to was, of all things, Lionel Richie’s “Hello.” Fortunately, there’s cooler stuff on the soundtrack: the Tom-Waits-in-Tehran opening number by Iranian band Kiosk, and some Morricone-ish fanfare by Federale, a group from Portland.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is bound to cause a stir in academic circles for the way that it blurs its Eastern and Western codes so thoroughly: making manifestly American settings stand in for an imaginary Iran, playing provocatively on the chador as Islamic garment and as vampire-cape substitute, having its heroine at once tender lover and murderous monster in a way that neither Anne Rice nor Stephenie Meyer would quite recognize. Overall, Amirpour’s film feels like an elaborately punkish code-scrambling gesture rather than a fully formed organic statement, but that doesn’t matter—it has style, grace, and imagination, and as artistic gestures go, could hardly be more devil-may-care. By the time it takes a final Aldrich-esque drive into the shadows, A Girl Walks Home has more than earned your attention—and got you wondering where that shadow-steeped road leads, either for its romantic duo or for Amirpour as audacious writer-director.

Watch A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/product/girl-walks-home-alone-night

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: 1984

A scary reminder of how easily totalitarian ideas and ideals crop up in societies and take fierce hold.

Film Review by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

Source: Spirituality & Practice

Winston Smith lives on Airstrip One, a part of Oceania. He resides in a shabby one-room apartment where his movements are monitored by a two-way telescreen. Winston works for the Ministry of Truth, where he rewrites history according to the party line.

Big Brother dominates the lives of Oceania citizens through psychological manipulation via the media. The totalitarian state seems to be in a constant state of war with either Eurasia or Eastasia. Hate rallies are designed to encourage allegiance to Big Brother; dissenters are publicly executed; and natural sexual behavior is forbidden.

Winston defies the authorities when he begins keeping a diary of his feelings. He goes a step further by beginning a love affair with Julia, another rebellious individual. O’Brien, a member of the privileged Inner Party, befriends Winston but later betrays him. The maverick is taken by the Thought Police to the Ministry of Love. Then in the notorious Room 101, O’Brien proceeds to torture and brainwash Winston. His ultimate goal is to replace the man’s love for Julia with love for Big Brother.

This screen version of 1984 is unrelentingly grim and ominous. Airstrip One seems more like a dank and dreary prison than a city. John Hurt is just right as Winston Smith, a stubborn individualist who refuses to reduce his life to a series of reductive slogans. Despite the haggard look, this British actor vividly conveys his character’s inner fire. Suzanna Hamilton plays Julia as flinty outsider who savors sex and sees it as a sacrament. In his final screen performance, Richard Burton plays O’Brien with convincing clout; he is an efficient bureaucrat whose cool demeanor masks an ugly love of raw power.

Although screenplay writer and director Michael Radford (Another Time, Another Place) gives the drama’s ending a twist that goes against the grain of George Orwell’s 1984, this intense film version of the book succeeds very well in depicting the totalitarian tendencies which tend to crop up in societies all over the world. The human spirit is violated when war is made into a vehicle for peace, when truth is twisted into disinformation and language is turned upside down; when loyalty to the state is built upon paranoia and neighbor begins betraying neighbor; and when surveillance takes away personal privacy and makes all dissent a crime. While many refuse to acknowledge the present reality of this Orwellian nightmare, others know that creeping totalitarianism thrives best when it moves quietly in the shadows.

Watch 1984 on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/11080278

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Vermilion Pleasure Night

“Vermilion Pleasure Night” (2000) was a Japanese late night variety show incorporating live-action and animated skits that run the gamut from surreal, sexy, profane, disturbing and satirical. Director Yoshimasa Ishibashi is an acclaimed artist whose installations have been featured at New York’s MOMA and London’s Tate Modern.

This premiere episode provides a sample of the recurring vignettes featured throughout the series including the Fuccon family (a dysfunctional family of smiling mannequins), Starship Residence (chronicling the misadventures of an alien bachelor and his neighbors), One Point English Lessons (a satire of English language learning programs), Midnight Cooking (a macabre musical cooking show), Cathy’s House (a live action skit evoking the setting and aesthetics typical of Barbie dolls), and random short scenes directed in the style of David Lynch films.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Cold Case Hammarskjöld

Review: COLD CASE HAMMARSKJÖLD, Pretzels of Truth and Performance Art

By Kurt Halfyard

Source: Film Anarchy

“This could either be the world’s biggest murder mystery, or the world’s most idiotic conspiracy theory.”

Two years before the JFK assassination, on the 18th of September 1961, the world was shocked by the suspicious death of the second serving Secretary-General of the United Nations. In a plane crash in Ndola, Rhodesia, Dag Hammarskjöld was the only person on board not horribly scorched in the ‘accident.’ Instead he was bloodied, and a playing card was tucked in his shirt collar.

Nearly six decades later, the UN is still (nominally) investigating the details of what was thought first thought to be an accident, then a targeted assassination, of a man who had designs on the political and financial independence of the African continent. In fact, U.S. President John F. Kennedy himself described the Secretary General as “the greatest statesman of our century.” The assassination theory holds several motive possibilities – various industrial interests active in the region (both then and now) or various clandestine military or mercenary operations taking orders from the US, the UK and Europe who had designs at odd with the ‘activist’ Secretary General.

There are crimes, and then there are crimes. Outside of the small circles of Denmark Television or offbeat cinephiliia, Mads Brügger is criminally unknown. The journalist, comedian, satirist, filmmaker, but above all, provocateur, has been twisting the documentary form into pretzels of truth and performance art for more than a decade.

In 2006, he toured an autistic theatre troupe though North Korea, cascading through a collection of political handlers and bureaucrats, to make a point about propaganda and totalitarian fear imposed on the so-called Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea. As if that stunt, The Red Chapel, was not fraught with enough risk, he then purchased illegal diplomatic credentials from the Central African Republic (CAR) to set up his own personal blood diamond operation (under the front of a match factory whose product would be manufactured by the local Pygmy population). By the time The Ambassador wowed Sundance attendees (and yours truly) in 2011, several of the ‘characters’ in the film, political figures in the CAR, had disappeared or been killed.

The Danish filmmaker takes large risks, some might say indefensible ones. Along with his countryman Lars Von Trier (whose outfit Zentropa produced The Ambassador), Brügger keeps plenty of his own skin in the game of his cinematic endeavours — for the sake of your education, and entertainment. He is a hell of a talented filmmaker.

With Cold Case Hammarskjöld, things go the full Errol Morris (Wormwood, A Wilderness of Error) investigation route. With the help of Göran Björkdahl, a Swedish activist/investigator who is in possession of the only part of Hammarskjöld’s plane that was not buried under the soil of the Ndola airport, Brügger uses every trick in the documentary playbook: re-creations, animations, historical footage, official and redacted document scavenging, and a lot of interviews with people who where sidelined, ignored, or simply unknown at the time.

Above all, Brügger recreates, in glossy cinematic terms, himself making the documentary itself. Form as function, as with any good conspiracy theory, things start to fold back on themselves in increasingly avant garde ways.

But there is purpose in this narrative trickery. By filming himself, twice, it offers Brügger the storyteller the opportunity to rope a Zodiac-level ‘filing cabinet ‘of names, facts, dates, and political organizations, together into a ‘lean in’ yarn of far reaching proportions. Two hundred old Secret Marine Societies, megalomaniac villains dressed in white, biological guerrilla warfare, the fallout of Apartheid, World War II fighter aces, assassins leaving Playing Cards in their victims’ collar, and of course, the fate of both a continent, and a fledgling World Government Body are all tethered together.

To say that the film’s 128 minutes is dense, is an understatement. Via this experimental technique (which of course the filmmaker acknowledges, in somewhat of a mea culpa, at one point) along with some pretty detailed, rational, detective work, makes the whole thing as seductive and addicting as Serial or The Staircase.

At one point, Michael Moore-style, Brügger and Björkdahl arm themselves with a high powered metal detectors, shovels, and a cigar (in the off chance they are successful), and go scouring the back-fields of the Ndola airport looking for the 50+ year old burial site of the plane. The authorities arrive. They are polite, but firm, regarding this activity. You are simply not welcome to do this kind of digging.

Cold Case Hammarskjöld has caused a stir in ‘papers of record’ such as The New York Times and The Guardian, reacting to the film compelling presentation and investigation of SAIMR, the South African Institute for Maritime Research, and its quack doctor, Lord Nelson cosplaying Commodore, Keith Maxwell, the “man in white”, who is said here of not only co-ordinating the murder of Dag Hammarskjöld, but also weaponizing AIDS virus for genocidal purposes, and ostensibly participating in bad amateur theatre.

The former may have been at the behest of the CIA and MI6, the latter was on his own personal time. Maxwell was a surreal combination of L. Ron Hubbard, and Colonel Kurtz, and Brügger condemns, mythologizes, exposes, at several points even mimics, him in the way only larger than life cinema can.

If there is a signature image across several of the films of Mads Brügger, it is that of an impeccably dressed man, wildly out of place, sitting on a skinny boat drifting on the current of a wide, and fast moving body of water. Here it is Göran Björkdahl, no closer to the truth of the matter, but still floating on the river of possibilites. We have learned things, both true and untrue, along the way.

Cold Case Hammarskjöld is the most engaging (and entertaining) documentary of the year.

Watch Cold Case Hammarskjöld on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/product/cold-case-hammarskjold