Category Archives: Video

Saturday Matinee: Alphaville

GODARD’S SCI-FI/NOIR ALPHAVILLE’ IS WITTY AND SUBVERSIVE

Alphaville‘s pulpy sci-fi plot acts as a warm coat of familiarity as Godard slyly subverts one genre trope after another.

By Brian Holcomb

Source: PopMatters

In Oliver Stone’s The Doors (1992) Ray Manzarek (Kyle MacLachlan) tells Jim Morrison (Val Kilmer) a story about his experiences working in the Hollywood of the late 1960s. He says he told a studio executive that he did not need a script to make a film. “Godard doesn’t use one,” Manzarek claimed. The executive replied, “That’s great… Who’s Godard?”

By the late ’60s, Jean-Luc Godard was a legend among young cinephiles. Beginning with Breathless in 1960 and ending with Weekend just eight years later, the caustic former Cahiers Du Cinema film critic made 15 films which can only be described as revolutionary. Both in terms of cinematic form as well as political and personal content, these films broke the old rules while inventing new ones. The use of handheld cameras, jump-cuts, natural light, and improvisation were both old and new things he popularized. Many of these ideas were used during the freewheeling days of silent cinema before filmmaking was industrialized and, in the mind of Godard and his “New Wave” colleagues, fossilized.

Godard wanted to provoke. But unlike some of his more didactic later work, these initial films are playfully provocative. Most of them are defined by their adversarial relationship to popular movie genres. Breathless is Godard’s deconstructed take on the crime film. A Woman is a Woman (1961) is his musical comedy.

Alphaville (une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution) (1965) is two genres for the price of one: science fiction and noir. Maybe it’s even a third genre as well. It can be argued that the film is just another Eddie Constantine “Lemmy Caution” flick. “Lemmy Caution” flicks were big business in France since the ’50s, and Constantine played the role in over a dozen of them. Created by British pulp novelist Peter Cheyney, Caution is either an FBI agent or a private detective, depending on which novel you read, but it doesn’t really matter. He’s less a character than a genre archetype and it’s the archetype that Godard wanted. Especially one that was already lost in translation: British novels about an American detective adapted into French films starring an American actor speaking French.

Constantine was synonymous with the role, so Godard simply dropped him like a found object into his dystopian science fiction plot. The old fashioned tough guy Lemmy Caution does not belong here. His simple macho values and violent responses are hilarious when placed into this new context. In one scene, he shoots and kills a man then attempts to question him. Caution appears to have no idea what question to ask anyway, as his bizarre mission pits him against a fascist sentient computer called Alpha-60, which rules Alphaville and forbids any expression of emotion. Caution is deadpan but filled with primitive emotions both violent and romantic. It’s no surprise that Godard considered calling the film “Tarzan Versus IBM”.

By the end of the film, Caution gives up trying to understand the computer’s semantic games and resorts to his base instincts to bring Alphaville down. Along with using his fists and a .45 automatic, Caution expresses love for Natacha Von Braun (Anna Karina), the daughter of Professor Von Braun aka Leonard Nosferatu (Howard Vernon) — the man who built Alpha-60. Natacha grew up in Alphaville and does not know the meaning of words like “Love”. Caution challenges her to understand the meaning and challenges Alpha-60 by telling it a riddle that it cannot possibly comprehend.

From this description, the film may seem like a cold intellectual exercise. A film made by Alpha-60 itself. But this isn’t the case. I find Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which is obviously inspired by this movie, to be a much colder experience. Alphaville is one of Godard’s wittiest and most emotionally moving. The pulpy sci-fi plot acts as a warm coat of familiarity as Godard slyly subverts one genre trope after another. Godard never really stopped being a film critic. His films were as much essays on how films worked as they were films themselves.

So Godard reveals the artificiality of B-movie fight scenes by presenting them as a series of posed comic book stills and gives Caution melodramatic theme music, which turns abruptly on and off at the most dramatically incorrect and hilarious moments. The excellent score by Paul Misraki shifts from this intentionally clichéd thriller music to beautiful and haunting pieces full of romantic longing.

This romantic theme is used most effectively at the end of the film, a scene which is a perfect example of what fellow French New Wave director Francois Truffaut called a “privileged moment”; brief moments in cinema when the film captures something intangible in a way no other art form could. As Misraki’s score builds, Godard holds on a lengthy closeup of Anna Karina, whose eyes are as hypnotic as any performer in film history. Karina’s expression slowly and subtly shifts from cold to warm and she ends the film by speaking the words she could not comprehend earlier: “Je vous aime…”

____________________

Watch Alphaville on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/15675583

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Belladonna of Sadness

Reconsidering Belladonna of Sadness: Still powerful after almost 50 years

By Carmen Antreasian

Source: Anime Feminist

A cult film originally released in 1973, Belladonna of Sadness can be read as a second-wave feminist work. However, in order to understand the film as feminist, it is important to emphasize that the film’s plot is based on Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière (translated as Satanism and Witchcraft or The Witch of the Middle Ages in English), originally published in 1862. In his book Michelet discusses his conception of the Witch’s way of life and the persecution the Witch faced by feudal Christian societies in the Middle Ages. Michelet defends the Witch in his book as a champion of love and healing and defends witchcraft as a prelude to science: “…we shall mark the beginning of the professional man as juggler, astrologer, or prophet, necromancer, priest, physician. But at first the woman is everything”. Belladonna of Sadness follows Michelet’s same view, combining this 19th century vision of the liberated witch with second-wave feminist ideology to create a flawed but fascinating work that invites revisiting even all these years later.

To those unfamiliar with the film, Belladonna of Sadness is the story of Jeanne and the persecution she faces as a woman in a feudal society. The story begins when newlywed Jeanne is gang-raped by the local baron and his attendants under the justification of “prima nocta”. When her husband falls ill, Jeanne becomes desperate and a clitoral/phallic demon appears to her and gives Jeanne wealth and influence as the village money-lender. She holds this role and this power until she is stripped of it–literally–and chased out of town. She ultimately “sells her soul to the devil”, which is the grown version of the initial phallic creature, and becomes a witch who lives apart from the village. Plague breaks out in the feudal society, and the villagers eventually join Jeanne, who builds a society that celebrates herbal medication and sexuality. Having lost power over the villagers, the baron offers her power as a means to control her knowledge; when she refuses to tell him, she is burnt at the stake.

This is a film written and directed by men (Yamamoto Eiichi and Fukuda Yoshiyuki) and is considered a Japanese “pink film”’ as it is includes graphic depictions of sex and nudity. Belladonna of Sadness uses its “pink film” attributes in order to demonstrate the plight of the main character Jeanne as an example of Michelet’s Witch. Jeanne’s sexuality is the focal point of her journey and the catalyst for the social changes that occur throughout the story.

Created during the Japanese feminist movement of the early 1970s, Belladonna of Sadness is a second-wave feminist film, and it’s impossible to talk about Japan’s women’s liberation without discussing the ideas of Tanaka Mitsu, arguably its most prominent leader. Tanaka fought against the popular notion of the woman as either a housewife or an object for male sexual pleasure. Instead, she advocated for the woman to be seen as an individual with agency over her own sexuality and shared her own life experiences with sexual assault, including rape and harassment, to inspire other women to support women’s liberation, a.k.a. uuman libu.

This seems to pair nicely with Jeanne: she’s initially (and presumably) destined to fulfill a wifely role in marrying her lover Jean but instead is forced into the role of sex object when brutally raped by the baron and his cronies, and gains agency as an individual through the awakening of her own sexuality. After this awakening she does not fall into the housewife/male-sex-object binary but gains power and instead assumes a leadership role in the village. However, the phallic nature of Jeanne’s sexual awakening complicates this viewpoint. To explore this, it’s crucial to look at Jeanne’s initial encounter with the little creature who awakens her sexuality before “it” becomes “him”– the devil/phallus character.

When she first meets the devil/phallus character, Jeanne is in a desperate position. Not only is she emotionally scarred from being raped, but she lives in poverty with her ill husband who, despite telling her they would move on from her assault, later attempted to strangle her. One night while her husband is asleep, a small clitoral-esque creature appears.

The clitoral creature states that it is her. It does not deny being “the devil”, but it is born of her desire. Her sexual awakening has begun. The clitoral creature then tickles her all over her body, making her laugh, and she questions how this small thing could give her power. Then it “teaches” her how to make it grow by rubbing itself in her hand, which turns “it” into a phallic creature that gives her sexual pleasure as she lays next to her sleeping husband. This is Jeanne’s first experience with masturbation, initiated by a clitoral-to-phallic creature, a personification of her individual sexuality—“I am you”—and summoned by her “screaming soul”. The agency of the “soul” is another important aspect of 1970s Japanese feminism, as Tanaka stated, “I want to have a stronger soul with which I can burn myself out either in heartlessness or in tenderness. Yes, I want a stronger soul.” Tanaka’s soul calls out for strength as Jeanne’s does for power, both qualities that were specifically reserved for men.

Jeanne’s individual sexual agency is exactly the kind of liberation Japanese feminists of the early 1970s envisioned, and in the film, it sets in motion Jeanne’s success within feudal society. Her sexual awakening was triggered not by the horrific rape she experienced beforehand but by her own, albeit guided, exploration of sexual pleasure without another person. However, it must be noted that this devil creature is gendered with a distinct male voice and phallic appearance.To discuss this, it’s helpful to bring in another element of the 1970s: the psychoanalytic female subject. This idea comes from Jacques Lacan’s theory of sexuation, conceived in 1972-1973. While Belladonna was in production as this theory was being published, it’s a useful way to boil down 1970s psychoanalysis to one analytical lens for the purpose of this essay.

Why use psychoanalysis and, of all psychoanalytic theorists, why Lacan, a man who once said that his brand of psychoanalysis wasn’t applicable to the Japanese? Both psychoanalysis and second-wave feminism were popular ways of thinking in the early 1970s that sometimes overlapped and often-times butted heads. Jeanne may be a feminist character, but she is also one created by men. Jeanne may be a character in a Japanese film, but she is also one based on a French man’s story of a witch in the European Middle Ages within a European social structure. And while Lacan might be thoroughly outdated in real life, his influential work still makes for a compelling tool of literary analysis.

Sexuation, to be dangerously brief, is Lacan’s theory of how a subject becomes a desiring subject through his/her sexuality. This theory relies on a binary, and there are different roles for male and female subjects. The female subject in sexuation fits one of three roles, two of which are to cater to the male subject and one that seeks what the male subject seeks: the “phallus”, otherwise known as power. Jeanne is the latter of the three. The phallus manifests when her sexuality is awakened; the phallus gives her power; when she is destitute and chased from the village, she seeks the phallus; again, the phallus gives her power. Jeanne fits the mold almost too perfectly… but does she?

If Jeanne were to truly fit Lacan’s mold as female-subject-who-seeks-the-phallus/power, then she would not be able to dismantle the patriarchal social structure once she becomes the leader of the village. Why? Because she would then be playing into a patriarchal structure herself, adhering to an identity constructed by men for a woman in power. When she first gains power and wealth in the feudal system, she continues to lead in accordance with it. She still pays and collects taxes—in fact, her husband becomes the tax collector—and she still meets with her superiors in the feudal system. Nothing systemic really changes except that she becomes the leader of the villagers and brings them wealth.

Jeanne is exposed to the violence and greed of those men for which the system was created once they deem her a threat to their power, and so she is eventually chased out of the village and away from the system completely. This is the moment when she “sells her soul to the devil”. It is a desperate moment, as was the very first time the clitoral-phallic creature appeared to her. This time, though, the creature is entirely phallic, monstrously large and referred to as the devil, but there is one very important detail to remember: “I am you.”

This phallic character, once a small creature on a spool of thread, is a manifestation of her sexuality. Yes, it is exceedingly heterosexual, and a product of male writers and animators, but Joanne still has agency to engage with the manifestation of sexual desire and independence she herself has cultivated. Albeit clearly depicted as masculine, the devil phallus does not adhere to the feudal social structure but rather an invitation to the possibility of something new, born of embodiment rather than socially constructed.

Bodily knowledge, although depicted heteronormatively, is what creates Jeanne’s new society. The beautifully animated scene of Jeanne’s sexual experience with the devil is also full of Yonic imagery. When the devil appears to her, he parts the clouds by flying down in a circular motion, revealing a clear sky without a sun. Just before the devil lands, however, he shoots out of a shape in this clear blue sky: vaginally-shaped pink, red and purple oval. This vaginal space appears to stand in for the sun and allows the devil to manifest on the earth. This phallus originates from the vaginal.

Once Jeanne and the devil’s intercourse climaxes, images of modern—okay, 1973-modern—entertainment, technology and everyday life flash before the viewer’s eyes, signifying that she made it happen. This is in accordance with Michelet’s message that it is the woman who was first to create and resonates with 1970s Japanese feminist Raicho Hiratsuka’s sentiment that “in the beginning woman was the sun”, evidence of the importance of the aforementioned Yonic imagery in the film. Jeanne’s embodied sexuality sparks the possibility for all that will be created, even that which is phallic.

Jeanne gets another chance at dismantling the feudal patriarchal social structure when the black death, better known as the Plague, destroys the village. One of the not-dead-yet villagers finds himself near her, and she cures him with what he refers to as “poison,” telling him “poison is medicine.” He goes back to tell the others, who spread rumors that she is a witch but run to join her because of her healing powers, sympathy toward others, and rejection of social hierarchies and sexual norms. On these foundations she builds her own society, one that is inclusive, even to those who have wronged her and come to her for help. She builds a society based on liberation, kindness, and open-mindedness.

She provides antidotes specifically related to female reproduction such as labor pain medication and birth control, access to which was a large part of the Japanese women’s liberation movement in the 1970s (and remains an issue there as it does abroad). People are free to have sex as often as they wish without worrying about the potential financial burden of having children. People are free to experiment sexually, shown in the orgy scene in Jeanne’s hair. Her new society is not a patriarchal one, but she also did not have to dismantle the previous patriarchal society to create her own. The Plague provides the conditions to build her feminist society separate from the existing feudal structure. Her society is not a rebellion or antithesis of the feudal structure but a revolutionary system of its own making.

Jeanne and her sexuality—from “selling her soul” to the devil/phallus, who is also a part of herself—demonstrate that a feminist society is possible, though its conception of what that might encompass is limited due in part to the restrictions of Michelet’s source material. The sexual symbolism in the villager’s activities are heterosexually binary, and the villagers all form man/woman pairs when they first engage with Jeanne’s society. The bodies of the villagers continue to be drawn as either clearly heteronormatively male or female as well.

The major exception is the non-heteronormative sexuality depicted in Jeanne’s alternative society during the long orgy scene in Jeanne’s hair, where the villagers are all connected in sexual positions and occasionally break out to showcase various other non-hetero sexual scenarios.There are moments of bisexuality seen in the orgy and one flash of two men together, but anytime a person strays from being either cis male or female, they are merged with an animal and meant to be comical. This lack of tender, intimate queerness even under liberation becomes the biggest failing of the film’s vision.

Ultimately, however, Jeanne and the villagers are forced to go back to feudal society. Jeanne’s husband comes to her, telling her she will be forgiven by the lord if she returns. She isn’t fooled by the lord’s blatant lie, but she knows that if she doesn’t go back, the lord will send troops to capture and kill her. She is in a lose-lose situation. The patriarchal structure proves its all-powerful authority, and that her separatism is impossible without dismantling the oppressive structures she fled. When she goes back, the lord does, in fact, offer her land in exchange for her knowledge.

He not only wants her power—the lord wants to indoctrinate her power into a patriarchal system, taking the feminine healer’s “witchcraft” and rebranding it as “science”. The lord desperately tries to get her to reveal her healing power by offering her more and more power in the feudal system, but Jeanne is not interested in being a part of his patriarchal hierarchy. She’s experienced the possibility of a feminist society and desires revolution over anything she could obtain in the existing structure.

During the film’s final moments, when Jeanne is burned at the stake, the faces of the women villagers watching her begin to change one by one to resemble her face, symbolizing the perpetuation of Jeanne’s influence. These villagers’ faces reflecting Jeanne’s face is a sign of Jeanne’s legacy. It is revolutionary in its admission that it’s possible to envision a society outside of the existing oppressive structure.

Watching the film in 2022 through an intersectional lens informed by evolving feminist and queer theories, Belladonna of Sadness may no longer seem progressive. The “girl power” message its male writers were trying to get across may be lost in its overwhelmingly graphic heterosexuality, and Michelet’s vision of The Witch may not resonate or hold the same power for contemporary viewers.

The homogeneity of the womens’ faces at the end of the film demonstrate that the “girl power” Jeanne had put in motion is homogenous. It suggests that there is only one type of woman that can grasp and perpetuate Jeanne’s vision. Through a lens of queer and critical race theory, the womens’ faces merely play into existing power structures, as the faces are all the same and, most importantly, all white with feminine traits such as big eyes, dark eyelashes, full pink lips. A truly radical depiction of Jeanne’s society in these face changes to push against patriarchal power structures would include a wide array of faces.

Through hindsight it may not hold up today in some regards, but I firmly believe that it is still revolutionary in that it depicts the possibility of a society based in the power of sexual freedom, healing, and care, rather than one that merely reconfigures existing patriarchal structures. The society Jeanne creates outside the feudal land is radical. Her society is necessarily birthed of the female body; even the phallus cannot come into being without her sexuality. Belladonna of Sadness is a historically important film that deserves to be revisited and reconsidered. It helps us better understand current feminist thought by knowing where we’ve come from and, in analyzing its flaws as well as its more deeply embedded subversions, allows us to push current critical theory even further.

____________________

Watch Belladonna of Sadness on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/584431

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: The Swordsman

By Fumiko

Source: Geek Culture

Finally, a Korean period drama that is all action, and more importantly, devoid of mindless zombies. If you’re looking for a gritty action film filled with spectacular sword-wielding stunt work, Joseon era drama and good ol’ warriors’ code, The Swordsman will definitely deliver enough to whet the appetite of any action fan.

Directed and written by Choi Jae-Hoon, the film is designed with meticulous care to costume and makeup while incorporating a whole trove of weaponry for satisfying fight sequences, showcasing a winning formula of mixing a period drama with martial arts. If the “Die Hard on a…” trope defined action cinema in the 90s, audiences are now in the realm of hyper-violent action films as defined by the likes of The Raid and John Wick franchises.

While the nature of The Swordsman leans it more towards a martial arts film with action taking precedence over an admittedly predictable plot, we can’t deny that the story moves along at a well-timed pace packed with amazing action sequences. It wastes no time on unnecessary romances or over-glorified gratuitous fight scenes, and we are thrown right into the heart of an intense chase scene right off the bat.

The prologue sees the protagonist, Tae-Yul (Jang Hyuk) desperately protecting the emperor against a coup led by Tae-Yul’s mentor Seung-Ho (Jeong Man-Sik). After the doomed battle and fall of Gwanghaegun of Joseon, Tae-Yul retires his sword and leaves for a peaceful life in the mountains. We find out that he does so for his daughter, Tae-Ok (Kim Hyun-Soo).

The movie takes place during the tumultuous transition times of the Ming-Qing dynasty, so peace for the retired swordsman is unfortunately broken. Like how most Hero’s journeys are written, Tae-Yul receives a call to adventure when he first encounters the thugs from Qing and led by Gurutai (Joe Taslim) in the market. However, like any hero’s journey goes, he refuses the call in favour of maintaining his hermit days to protect Tae-Ok.

However, we see that Tae-Yul now suffers from deteriorating eyesight and this spurs Tae-Ok to venture down the mountain alone. Tae-Yul’s world is soon shattered when his daughter is taken from him and he is forced to cross the threshold and return to the world of the swordsmen.

Despite its gentle start, featuring sunny days in the mountains for the father-daughter duo, violence and swordplay soon permeate the plot. The swelling score that rolls through the film propels the momentum of the action as Tae-Yul slashes down enemy after enemy.

The wall-to-wall action hits its climax when Tae-Yul makes his way to Lee Mok-Yo’s (a minor unscrupulous noble played by Choi Jin-Ho) residence to face endless waves of Gurutai’s men. The scene is made all the more climatic by Tae-Yul’s quiet entry as compared to the carnage onscreen seconds before when the men, armed with guns, shot down Lee’s entire platoon of guards.

Cue wild barrage of gunfire and some Matrix-like slow-mo bullet-dodging action, Tae-Yul’s onslaught against the men is relentless. With only a sword, he is able to slice through the first wave of gunmen and power through a group of ninja-like masked assassins. Coupled with smooth continuous shots of the action, the entire scene was bloody with a capital B. But, the blood at some points did tend to look obviously digital and could have worked better with more realistic spurts.

Amidst all the action in The Swordsman, we see a build-up to the final boss fight with Gurutai via the menacing hold he has over both the Joseon officials and the three barbaric thugs. Being the cream of the crop in terms of sword skills, the final fight is an escalating intensive sword slashing sequence. The only issue we had with the scene was that it felt as though the final fight ended too soon and we’d love to have seen more of the two characters pitted directly against each other.

So yes, this leads to the few gripes we have with the film. Seung-ho’s first battle against Tae-Yul implies that he is a much better swordsman than our protagonist, but in the film, he ends up doing very little swordwork. Maybe, it could have been related to the aged warrior’s philosophical outlook on swordsmanship changing due to the regressive state the nation was in after he led the coup. Most of his action is only ever mentioned in passing or through small fights that seem ornamental compared to his opening battle in the prologue.

Similarly for Gurutai, who is played by martial-arts expert Joe Taslim (of The Raid fame). As a fierce swordsman with his own albeit twisted code of honour, he struts around with an air of superiority as the Joseon warriors are unable to touch him in fear of retaliation from the powerful Qing kingdom. Gurutai is first introduced in a scene with a suaveness in contrast with the flittering Joseon nobles and doesn’t hesitate to expose his menacing aura. One would expect more action from the character throughout the movie, considering that the actor playing him is known for his spectacular long take fight sequences, though we can understand that they may have curbed this due to the want for a more intense foreshadowing and build-up of mystery surrounding the “final boss” of this action film.

Yet, aside from these small action woes, the film hits the nail on the head characterisation wise.

Jang Hyuk was able to express so much with so little said as Tae-Yul is a man of few words but with a strong code of honour. He spends the first half taking down enemies with a cane, thwarting villains without unsheathing his sword and just glaring them down, attesting to his skills as a warrior and morals (and ramping up his coolness points). He would rather avoid fights when possible, even lowering himself on his knees at one point for his daughter’s safety.

However, despite being a silent warrior with a puppy-dog face portrayed by Jang Hyuk, the swordsman doesn’t hesitate to switch back to killing with actual weapons when he realises that submission is no longer a way to maintain his peace.

K-pop fans will also be pleasantly surprised to see BTOB’s Minhyuk transform into a rugged swordsman as he portrays the younger version of Tae-Yul. The Swordsman marks his big-screen debut, and here, the singer shows off his acting chops with strong facial expressions, swift movements and intense gazes.

Tae-Yul shares a close bond with his bubbly daughter who adds a breath of fresh air to his quiet life. We appreciate how the film doesn’t go with the overused trope of a warrior retiring his blade due to a painful past and instead see that Tae-Yul did so in order to protect Tae-Ok with a peaceful sheltered life away from the brewing chaos. When Tae-Yul drops the line, “My daughter my nation,” it can be taken figuratively. But, there is another explanation behind that line which viewers will have to watch to find out.

Kim Hyun-Soo plays the daughter who is bold, yes; and acts with a will well ahead of her time but not in a brash manner. She cares deeply for her father and respects him, only showing defiance out of concern for his ailing eyesight which he refuses to tend to. How the film was trying to portray Tae-Yul’s onset of blindness could discombobulate audiences though, as the weird ringing and wooziness made it seem that he had some bad head trauma and was not simply going blind. The film itself doesn’t elaborate on the illness either so everything is based on speculation.

Through Tae-Ok, the film takes a break from the action at times and opens up towards the period drama aspect with her adventure down the mountain and frolicking through the colourful market streets. It’s too bad that she didn’t get more screen time to show off her character and demonstrate more of her spunk. But perhaps, it wouldn’t have fit into the narrative or may have taken up too much time.

Unlike Tae-Yul, Gurutai is a man of many words and has a lot to say about the Joseon people and their nobles. It is pretty impressive with how well Taslim, an actor from Indonesia, is able to pronounce and delivers each line without faltering and even manages to infuse the right amount of menace in each syllable. He even executes the older historical accent that some Korean period dramas will use, with a natural lilt which is a huge achievement even for native Korean speakers. What’s more, this is also his first time doing action with a sword, yet he executed the moves flawlessly, showing his true martial art prowess.

Leading a trio of ruthless thugs and a band of bandits they terrorise the Joseon villages with slave debts which the Joseon guards have no choice but to close both eyes too. And for all his code of honour dictates, it becomes his weakness as he is quickly blindsided by it when Tae-Yul makes an unexpected move in the final confrontation.

The trio of thugs burst into the scene in a flurry of hoofbeats and over-the-top hairdos. Their brutality is established with their merciless beatings of a defenceless villager and savage choice of weaponry. Yet, despite all their bullying, they are easily overwhelmed by our protagonist. Though the fact that they could sense that Tae-Yul was skilled with a sword, without being fooled by his meek demeanour as others were, could attest to their experience in fighting and swordplay.

And as with how most period dramas are fashioned to match the ways of that time period, the women are treated more as mere decorative figures or transactional goods. Thankfully, the film does not have drawn out gratuitous scenes with regards to their low treatment. Moreover, we do have some girls inside who attempt to subvert the norms such as the trading port lady and Tae-Ok herself.

Furthermore, aside from the epic choreographed fight scenes, the film pays diligent attention to detail too. The costume designs for the main characters are simple but effective in portraying their personalities and statuses. Even the makeup is top-notch and consistent throughout, paying special care to the cuts and old injuries that the characters bear.

The sound design is nothing to ignore too and if anything has to be lauded for its ability to feed to the action. Every draw and swing of the sword is accompanied by an answering ring and the thuds and thumps help every blow feel more weighted and real. Even the simple sounds such as the clicks and clacks of the nobles’ accessories and the crunching of gravel beneath the guard’s boots helped to develop the look of the character beyond what can be seen visually (ASMR anyone?). These small sound effects help build the intensity of blood-pumping scenes due to its contrast with the escalation of noises brought about by the chaos.

The Swordsman is a wonderful blend of meticulously choreographed swordplay and enough drama to make us invested in the characters despite its simple plot. The film’s ruminative tone is interspersed with well-paced action and gentle moments and even ends on a bittersweet heartwarming note. It truly is up to scratch with what a good action film should look like and is a huge accomplishment as a directorial debut for Choi.

Summary

The Swordsman is an impressive Korean period action film filled with meticulously choreographed swordplay and complex characters which will satisfy any die-hard fans of this genre.

Two for Tuesday

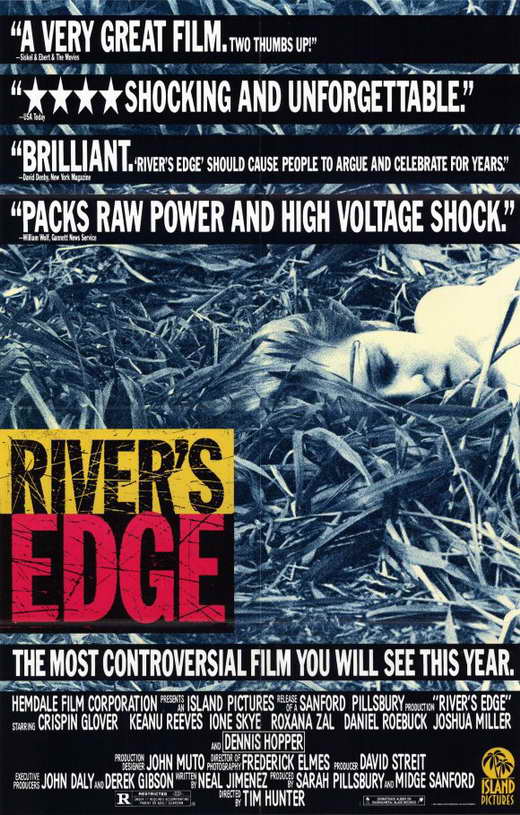

Saturday Matinee: River’s Edge

By Roger Ebert

Source: RogerEbert.com

I remember reading about the case at the time. A high school kid killed his girlfriend and left her body lying on the ground. Over the next few days, he brought some of his friends out to look at her body, and gradually word of the crime spread through his circle of friends. But for a long time, nobody called the cops.

A lot of op-ed articles were written to analyze this event, which was seen as symptomatic of a wider moral breakdown in our society. “River’s Edge,” which is a horrifying fiction inspired by the case, offers no explanation and no message; it regards the crime in much the same way the kid’s friends stood around looking at the body. The difference is that the film feels a horror that the teenagers apparently did not.

This is the best analytical film about a crime since “The Onion Field” and “In Cold Blood.” Like those films, it poses these questions: Why do we need to be told this story? How is it useful to see limited and brutish people doing cruel and stupid things? I suppose there are two answers. One, because such things exist in the world and some of us are curious about them as we are curious in general about human nature. Two, because an artist is never merely a reporter and by seeing the tragedy through his eyes, he helps us to see it through ours.

“River’s Edge” was directed by Tim Hunter, who made “Tex,” about ordinary teenagers who found themselves faced with the choice of dealing drugs. In “River’s Edge,” that choice has long since been made. These teenagers are alcoholics and drug abusers, including one whose mother is afraid he is stealing her marijuana and a 12-year-old who blackmails the older kids for six-packs.

The central figure in the film is not the murderer, Sampson (Daniel Roebuck), a large, stolid youth who seems perpetually puzzled about why he does anything. It is Layne (Crispin Glover), a strung-out, mercurial rebel who always seems to be on speed and who takes it upon himself to help conceal the crime. When his girlfriend asks him, like, well, gee, she was our friend and all, so shouldn’t we feel bad, or something, his answer is that the murderer “had his reasons.” What were they? The victim was talking back.

Glover’s performance is electric. He’s like a young Eric Roberts, and he carries around a constant sense of danger. Eventually, we realize the danger is born of paranoia; he is reflecting it at us with his fear.

These kids form a clique that exists outside the mainstream in their high school. They hang around outside, smoking and sneering. In town, they have a friend named Feck (Dennis Hopper), a drug dealer who lives inside a locked house and once killed a woman himself, so he has something in common with the kid, you see? It is another of Hopper’s possessed performances, done with sweat and the whites of his eyes.

“River’s Edge” is not a film I will forget very soon. Its portrait of these adolescents is an exercise in despair. Not even old enough to legally order a beer, they already are destroyed by alcohol and drugs, abandoned by parents who also have lost hope. When the story of the dead girl first appeared in the papers, it seemed like a freak show, an aberration. “River’s Edge” sets it in an ordinary town and makes it seem like just what the op-ed philosophers said: an emblem of breakdown. The girl’s body eventually was discovered and buried. If you seek her monument, look around you.

____________________

Watch River’s Edge on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/12027310