By Peter Sobczynski

Source: RogerEbert.com

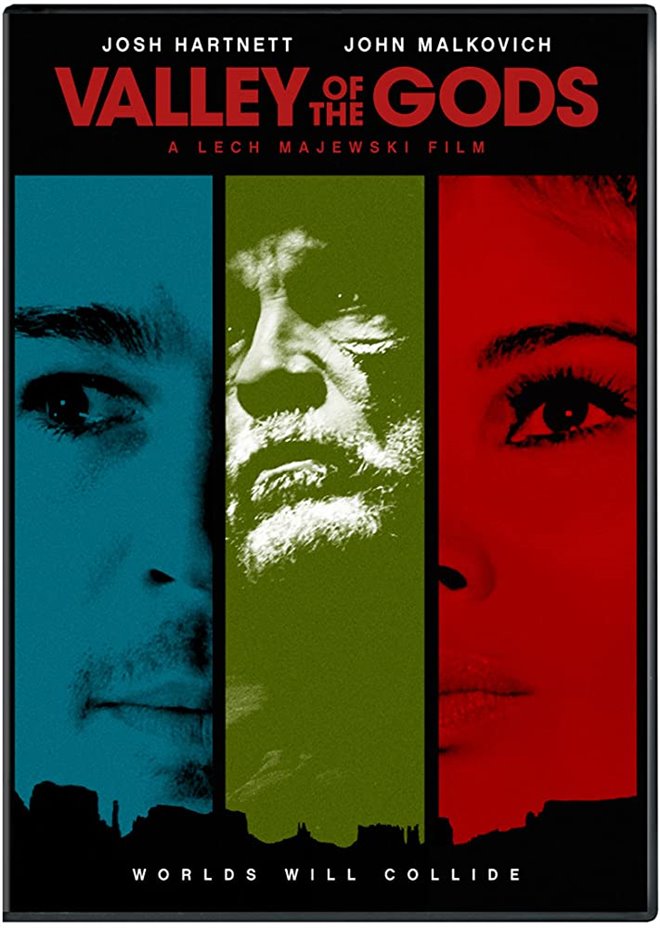

Of all the films this year that have been forced by circumstances to make their debuts via home video and streaming services, I can’t think of one that I would’ve rather seen in a theater than “Valley of the Gods.” This is partly because it is indeed a large-scale drama with a grand visual sweep that presumably needs a big screen to be properly appreciated. However, the real reason I wish that I could have seen it in a theater is to be able to see the faces of the other audience members once the end credits started rolling. My guess is that their facial expressions would greatly resemble those of the first night crowd for “Springtime for Hitler” at the end of the opening number. This is a movie so strange, bizarre and so unclassifiable that as soon as I was done watching it, I contacted my editor to see if deploying the phrase “batshit crazy” would be acceptable. It was approved but I have decided not to employ it on the basis that even that description undersells the experience.

As the film opens, a man (Josh Hartnett) arrives at the Valley of the Gods, an area of southeastern Utah near Monument Valley where the spirits of Navajo Indian deities are said to reside within the enormous stones on display. The man pulls a desk out of the back of his car and begins writing, in longhand, of course. In due time, we learn that he is John Ecas, an advertising copywriter whose life has collapsed since his wife (Jaime Ray Newman) left him, evidently for her hang gliding instructor. His therapist (John Rhys-Davies) suggests that the best way for John to cut through all the absurdity that he sees in the world is to beat it at its own game by doing things that are even crazier—climbing up a mountain face while dragging all of his pots and pans with him or walking the streets both backwards and blindfolded. Having accomplished those feats, John has now decided to write the novel that he has always dreamed of penning and while I cannot be 100% sure, it is implied that most of the rest of the film is a visualization of what he is creating.

This eventually introduces us to Wes Tauros, the richest man in the world, and rumored to have gone mute following a personal tragedy. He is played by John Malkovich, who is not exactly the first person one might think of to play a mute. Anyway, he’s in the midst of closing a deal to acquire the mineral rights to the Valley of the Gods in order to mine for uranium, a move that divides the Navajos still living there between those who want the money that they will receive as part of the deal and those upset that the development of the land will desecrate what they consider to be holy ground. Eventually, John turns up at Tauros’ super-lavish estate in order to write the man’s biography but discovers things that are peculiar, even by the standards of a character played by John Malkovich.

By most critical standards, “Valley of the Gods” is a film that starts off as being fairly berserk and quickly becomes frothing mad. It feels as though writer/director Lech Majewski had a marathon of the films of Terrence Malick and the recent works of Wim Wenders and decided to try to make something that would combine the two, minus the lucid plotting. The narrative, which unfolds via a prologue and ten separate chapter headings, is, to put it charitably, a mess. The various plot threads involving the rich man, the tormented writer, and the Navajos are largely inscrutable and they do not so much weave together towards the end as much as they clumsily crash into each other. Too often, Majewski abandons them entirely to go off onto strange tangents that range from Tauros catapulting a luxury car over a cliff vis some dubious effects work, to the scenes in which Keir Dullea turns up as the rich man’s spectral butler. (This may indeed be the most bewildering film that Dullea has ever appeared in and you know what his most famous credit is.) Then there is Bérénice Marlohe, who turns up in the world’s stretchiest limousine but otherwise does nothing but get a makeover and appear in what is only the film’s third most ridiculous sex scene. (The winner, FYI, is the bewildering sequence where one of the Navajos climbs up a giant rock formation and, uh, has sex with it.)

So yeah, the movie doesn’t “work,” as they say. And yet, even though it pretty much goes off the rails right from the start, never to return, I never quite minded. The film may be nuts but it certainly isn’t boring and there is never a moment where you feel the plot gears grinding away—this is definitely a movie that moves to the beat of a different drummer, even when it seems as if the drummer in question is Keith Moon. Additionally, it has a formal beauty to it that can’t be denied and which is frequently ravishing to behold—there are times when you just want to sit back and let the whole thing just wash one you. I also admired the willingness of actors like Hartnett and Malkovich to go way out on an artistic limb by taking part in it.

“Valley of the Gods” is a film that most people may find to be, at best, wildly uneven and frequently ridiculous and I cannot disagree with those assertions. However, I am still kind of happy that I saw it and I know that there are things in it that I will remember long after most of the more conventional movies of late have faded away. If you are someone who has in the past embraced such wonderfully unrestrained and seemingly foolhardy cinematic visions as Emir Kusturica’s “Arizona Dream” (1994), Richard Kelly’s “Southland Tales” (2006) or the Werner Herzog title of your choice, you might want to check this one out for yourself. If you do, be sure to stick it out for the jaw-dropping finale in which … well, you wouldn’t believe me even if I told you.

____________________

Watch Valley of the Gods on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/13724818