Category Archives: Video

Saturday Matinee: Final Cut

REVIEW: “Final Cut” (2022)

By Keith Garlington

Source: Keith and the Movies

It’s hard to believe that it has been twelve years since French filmmaker Michel Hazanavicius won his Best Director Academy Award for the Best Picture winning “The Artist”. While it has become somewhat fashionable in some circles to dismiss that brilliant 2011 film as unworthy, I still hold it in incredibly high regard as a delightful ode to a bygone cinematic era.

Hazanavicius’ latest film couldn’t be more different. “Final Cut” is a meta zombie comedy that is an open-armed tribute to cinema, a love letter to genre filmmaking, a celebration of creative collaboration, and just an all-around wacky piece of work. It’s a faithful remake of Shin’ichirô Ueda’s 2017 cult hit “One Cut of the Dead” but with its own French twist. It’s a consistently clever and routinely funny concoction that sees Hazanavicius and his all-in cast having the time of their lives.

Describing “Final Cut” to those who haven’t seen “One Cut of the Dead” is a bit of a challenge because the less you know going in the better. The film’s unorthodox structure plays a big part in making it such a fun experience. It’s a case of a filmmaker showing you one thing and then adding an entirely different perspective later on. I know that’s vague, but suffice it to say Hazanavicius has a field day playing with his audience’s expectations.

The spoiler-free gist of the story goes something like this. Romain Duris plays Rémi Bouillon, a frustrated filmmaker who signs on to direct a low-budget zombie short film for an upstart streaming platform that specializes in B-movies. But there’s a catch. The 30-minute single-take film is to be shot and streamed LIVE! It’s an unheard of undertaking but one the platform’s ownership has already pulled off in their home country of Japan. Now they want to do it in France.

Rémi is hesitant to take the job at first, seeing it as a doomed-to-fail project. But with the encouragement of his wife Nadia (Bérénice Bejo) and with hopes it will rekindle his relationship with his aspiring filmmaker daughter Romy (Simone Hazanavicius) he agrees.

Soon he’s on location dealing with a smug high-maintenance lead actor (Finnegan Oldfield), his inexperienced lead actress Ava (Matilda Lutz), a supporting actor who can’t stay off the bottle (Grégory Gadebois), and the demands of domineering producers who don’t prescribe to the notion of a director’s creative freedom.

As “Final Cut” shifts to the show’s production phase things get crazy and we gain an entirely new perspective on everything we’ve seen up to that point. Hazanavicius drenches his audience in blood, gore, and countless zombie horror tropes which is a big part of the fun. That said, it’s never the slightest bit tense or scary but neither does it try to be. It’s much more of a comedy, full of running gags, fun characters, an infectious B-movie charm, and a surprising level of warmth that I never expected.

Watch Final Cut on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/13547325

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Labyrinth of Cinema

By Simon Abrams

Source: RogerEbert.com

Japanese filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2016, about three years before he completed “Labyrinth of Cinema,” a trippy anti-war drama about Japanese war movies, of which Obayashi re-creates, parodies, and criticizes in one long movie within his movie. Or really, it’s one long movie marathon within Obayashi’s movie since “Labyrinth of Cinema” takes place at an evening-long war film festival hosted by Setouchi Kinema, a small Hiroshima movie theater that’s putting on one last show before permanently closing.

The plot is simple enough to be irrelevant: three bright young things— teeth-picking film historian Hosuke (Takahito Hosoyamada), enthusiastic film buff Mario (Takuro Atsuki), and aspiring gangster Shigeru (Yoshihiko Hosoda)—chase after chaste 13-year-old Noriko (Rei Yoshida) after she tumbles into the Setouchi Kinema’s movie screen, and becomes part of Obayashi’s unstable meta-narrative. By the way: Obayashi died of lung cancer a year and a half ago. You can tell that his death weighed on him just by watching “Labyrinth of Cinema,” his last movie, a three-hour living will, and a dazzling curtain call.

The movie’s Hiroshima setting gives away its personal nature since Onomichi, Hiroshima is director/co-writer/co-editor Obayashi’s hometown and also the main location for some of his movies, including the 1983 bubblegum-psych fantasy “The Girl Who Leapt Through Time.” Obayashi is best known to American cinephiles as the director of the 1977 day-glo nightmare “House,” a fizzy horror-fantasy that only became an international cause célèbre in 2009 after it screened at the New York Asian Film Festival and a few other noteworthy events. In “Labyrinth of Cinema,” Obayashi (along with co-writers Kazuya Konaka and Tadashi Naito) tries to sum up what he’s learned and tried to convey through filmmaking in a volatile auto-critique of movies as both seductive propaganda and palliative empathy machines.

Obayashi uses green-screen technology and cheap (but effective) computer graphics to dramatize folksy anecdotes about filmmakers like John Ford and Yasujiro Ozu, which he sandwiches between brutal and/or sentimental episodes about local war crimes and counter-cultural resistance. Sometimes Obayashi quotes poetry, particularly by Chuya “Japan’s Rimbaud” Nakahara. Sometimes, a cartoon character or samurai folk hero (Musashi Miyamoto?!) steals a scene or two. A few characters, like the time-traveling authorial stand-in Fanta G (drummer Yukihiro Takahashi), talk about movies as a beautiful, essential lie that’s first used as a balm and a distraction, and then also considered as a runway to a brighter and still unimaginable future. You give Obayashi three hours of your time, and he’ll give you a brilliant headache.

You might watch “Labyrinth of Cinema” and wonder where the hell this all came from. Like Obayashi’s recent war trilogy (2011-2017), and many of his earlier features—and short movies and TV commercials—“Labyrinth of Cinema” constantly reminds you that it’s “A Movie.” Before Obayashi’s movies begin, the words “A Movie” are usually presented on-screen in a frame within the image’s frame. So in “Labyrinth of Cinema,” Obayashi’s characters are often re-framed by small circular frames within the camera’s frame. Sometimes these images flip around on-screen, so that a character who was on the left side of the screen is now upside, or on the right, as if they were in conversation with themselves, the viewer, and anyone else who’s watching. There are also a surprising number of fart jokes and some callbacks to older Japanese movies like “I Am a Cat,” “The Rickshaw Man,” and “Wife! Be Like a Rose.” “Labyrinth of Cinema” is a lot of movie.

Obayashi’s various projects are instantly recognizable, given his usual combination of mistrust and fascination with movies as an expression of wish fulfillment and nostalgia. So it’s not surprising that his view of the past—and the cinematic image—is never really seductive in “Labyrinth of Cinema.” Cheerfully naïve characters get lost in their companions’ comforting, half-remembered memories, and never stop to wonder why one thing inevitably leads to another, and another, and another. They float around on-screen, unmoved by the laws of gravity or physics and unable to hide in whatever photo-booth-quality backdrop surrounds them. Obayashi’s characters all half-know and half-hope that they’ll live to see the next scene, so they take their time learning how to ride the ever-breaking tidal wave of Japanese history according to Nobuhiko Obayashi.

“Labyrinth of Cinema” is tremendously affecting, frequently beguiling, usually exhausting, and on, and on, and on. An indulgent ramble from an innovative surrealist who was always sensitive and even suspicious of his own work’s impact—as a tool for advertising, political whitewashing, and pure sentimental indoctrination. On his out way the door, Nobuhiko Obayashi left us wondering how he got all the way from “House” to here without losing faith in humanity and his art; I don’t know, but “Labyrinth of Cinema” is still there anyway.

Two for Tuesday

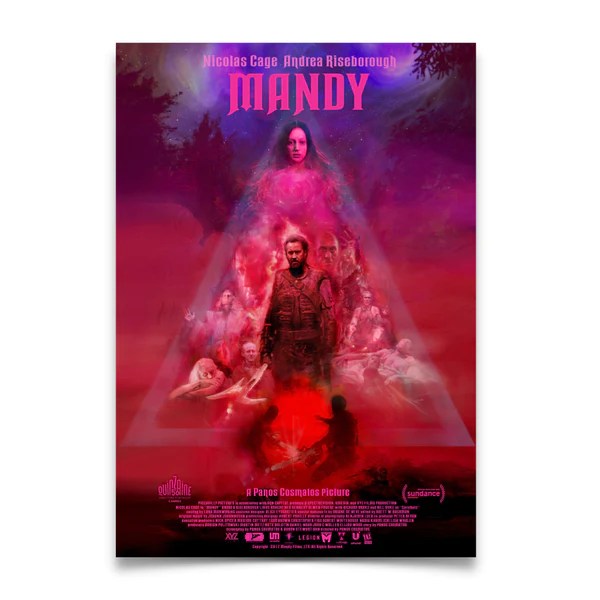

Saturday Matinee: Mandy

By Brian Tallerico

Source: RogerEbert.com

More than most movies, it’s hard to know where to begin with an appreciation or critique of Panos Cosmatos’ “Mandy.” It’s a really difficult film to capture tonally and even narratively in a review, largely because it is such a stylish, visceral experience that it demands you give yourself over to it actively instead of passively analyzing it. On the one hand, it’s a thriller, of sorts, a vengeance piece about a man killing those who destroyed his life. But, man, does that not really capture the experience of this movie. Some have compared it to an ‘80s heavy metal album cover sprung to life, but that’s only part of “Mandy,” and doesn’t convey the emotional depth that saturates every frame. And then there’s the fact that “Mandy” is kind of two movies in one, a slow-burn journey into hell in the first hour and a blood-soaked climb out of it in the second. Did I mention the chainsaw fight yet?

Nicolas Cage stars in “Mandy” as Red Miller, a lumberjack who lives a quiet life in the woods with his girlfriend Mandy, played by Andrea Riseborough. One day, Mandy catches the eye of a cult leader named Jeremiah Sand (Linus Roache), who proceeds to conjure motorcycle-riding demons to steal the girl and make her one of their own. In the process, Red is tortured and nearly killed. The first half of “Mandy” is filled with long, color-saturated takes of impending doom. Even casual behavior like quiet scenes between Mandy and Red have a foreboding nature, and then the film peaks in the middle with a waking nightmare as Red sees something no one should ever see happen to the love of his life. Deeply traumatized, Red is destroyed, and there’s a sequence in which Cage drinks an entire bottle of booze (well he ingests the stuff that isn’t poured on his wounds) while in his underwear, howling like an injured animal. It’s going to be GIF-ed and mocked, but it’s actually a great bit of acting, conveying a man not just mourning or in grief but literally destroyed.

Like a character in a Queensrÿche concept album, Red emerges from this destruction with his plans for vengeance. With a title card that divides the film in half, “Mandy” then becomes the movie that most people will remember in that it’s about Red working his way through both the demons that Jeremiah conjured and, inevitably, the gang itself. The heavy metal comparison is apt not just because the genre often included figures like the nightmarish creations that Jeremiah brought to life but in the very structure of “Mandy,” which unfolds in a very untraditional manner in both halves. Scenes play out like songs on an album, episodically cast in extreme color palettes that amplify the trippy, surreal natures of the entire experience. “Mandy” is a fascinating genre exercise in that it is as untraditional a horror movie as you’ll see this year but also relies on so many classics of the form. It is, at its core, a downright biblical tale of evil and vengeance.

It’s also pretty bad-ass when it comes to stand-out moments, particularly an already-acclaimed fight with two men wielding chainsaws like they’re swords. It’s a perfect blend of the old and new in “Mandy” and a distillation of what the film does well in how it takes a familiar good vs. evil sequence and twists it to fit Cosmatos’ vision.

Having said that, there are times when I felt the length of said vision. “Mandy” runs over two hours, and a little of its style goes a long way. I think there’s a masterful version of this movie that runs notably shorter, but that doesn’t mean there’s not an unforgettable one the way it is right now.

One more thing before you go on this journey with Nicolas Cage: the incredible Johann Johannsson (“Sicario,” “Arrival“) does the best of his career in this, his final film composition. The score here is another character, a series of screeching, violent noises that add to the tone of the film in ways that can’t be overstated. The film simply doesn’t work without it. And, as much as I like other parts of the movie, Johannson’s work alone justifies a viewing. It reminds us how much we lost by his early passing.

Watch Mandy on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/12253438

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Shadow

By Matt Zoller Seitz

Source: RogerEbert.com

In retrospect, it seems hard to believe that director Zhang Yimou didn’t make his first wuxia-influenced historical action film until two decades into his career, after a string of intimate yet visually striking dramas. But the double-hit of “Hero” and “House of Flying Daggers” (both released in 2004 in North America) reinvented him as one of cinema’s foremost directors of intricate mayhem, designed, lit, and edited with such care as to make the cliche comparison between action pictures and musicals feel not just fresh, but deep. Zhang never quite climbed to that peak of global crossover again. His family drama “Coming Home” and his remake of the Coen brothers’ “Blood Simple,” titled “A Woman, a Gun, and a Noodle Shop” were more intriguing than compelling, and his recent big-budget international coproductions (“The Flowers of War” and “The Great Wall“) felt more like ambitious financial undertakings than artistic ones.

“Shadow,” a tale of court intrigue sprinkled with giddy duels and scenes of armored soldiers clashing, isn’t quite a return to form; Zhang’s first two action pictures were so nearly miraculous that it’s hard to imagine them being equalled. But it’s filled with so many remarkable images, particularly in its middle section, that fans of palace intrigue and metaphorically ripe violence will find plenty to like.

Be warned going in that the first half-hour of “Shadow” is a pretty laborious setup: mostly characters walking in and out of rooms and announcing how they are related to each other, in terms of both bloodline and power dynamics. King of Pei (Zhang Kai), a snippy little despot, is still angry that a neighboring city that used to belong to his kingdom is now in the control of a general named Yang (Hu Jun), who won it in a duel. The king wants to get the city back somehow, or at least gain a foothold in it, so he offers his sister Princess Qingping (Guan Xiaotong) as a wife for Yang’s son, only to be insulted by a counteroffer of making her a concubine and presenting a ceremonial dagger as a gift. To further complicate things, the king’s Commander (Chinese star Deng Chao) just returned from challenging the general to a duel without authorization from higher up.

And wouldn’t you know it: the Commander isn’t even really the commander. He’s a double named Jing (also played by Chao) who’s been trained from childhood to take over for the Commander if circumstances demand it. And they do: the Commander is hiding in a secret chamber beneath the royal city, recovering from a grievous wound he sustained in the aforementioned duel with the general that resulted in the other city being lost. The only person who knows about the subterfuge is the Commander’s wife Madam (Sun Li), who quite naturally starts to develop feelings for her husband’s double.

The expository stuff at the front of the film isn’t inherently awful—it’s necessary to understand the large-scale violence that dominates the rest of the story, and the cast does a fine job of balancing simplicity and stylization with psychology. But aesthetically, it doesn’t begin to hint at the splendors that await, and it promises a richness of characterization (particularly among the secondary players) that the movie, which is often pitched at the level of a brilliantly designed video game, doesn’t quite deliver. (Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa—a major influence on Zhang whose works include “Kagemusha,” another historical action/military movie with a secret double at its heart—was better at making the talky bits exciting, too.)

Once the action kicks in, though, “Shadow” is on rails. Zhang, co-screenwriter Li Wei, cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding, production designer Horace Ma, and costumer Chen Minzheng work in seemingly perfect harmony to create a visual scheme that the director has said is based on the brush techniques of Chinese painting and calligraphy. The world they present would read as black and white (and grey) were it not for the flesh tones of the actors’ faces and bodies, and the voluptuous dark blood that splatters the screen whenever swords, knives, arrows, and crossbow bolts start to fly.

It’s impossible to understate how thrilling “Shadow” is during its middle section, when Zhang is crosscutting between the increasingly knotty intrigue in two cities, a second duel that we’ve been building toward for 45 minutes, the romantic tension between the Commander and his wife and his double, and a large-scale military action that’s intended to retake a city.

Confidently showy in a manner that evokes the most dazzling sequences in Zhang’s action classics, the movie takes symbolism that might seem simplistic and overdone (such as the prominent display of the yin and yang symbol in both dialogue and sets) and makes them feel organic to the tale, not in the manner of a novel or play, but an opera or art installation or graphic novel. The true yin and yang of the film is its expressive balance of masculine and feminine elements of design and choreography, especially as they’re expressed in combat.

The bluntly macho shapes of swords and halberds (as swung and thrust by confident, scowling men) are contrasted against razor-edged umbrella weapons deployed with deliberately feminine motions (by men as well as women; when combatants get in touch with their feminine side, the movie suggests, they’re able to achieve their goals in different, often surprising ways). The bearers of these killer umbrellas practically waltz into combat with them, hips swaying demurely, then use them as toboggans to carry them down steep, muddy hills. A sequence where an umbrella battalion tries to retake an occupied thoroughfare during a rainstorm attains a peak of controlled madness reminiscent of some of the wildest scenes in “Kung Fu Hustle,” a classic that wasn’t afraid to go full Looney Tunes. When Zhang crosscuts between a duel on a rainy mountaintop and a zither battle happening in a subterranean chamber, with the zither music providing the sequence’s melody and the clanging blades percussion, the essence of action cinema is distilled.

When the movie decelerates in its third act, the better to resolve all the plot particulars laid out in the first section, it’s hard not to feel let down. It’s like that feeling where you disembark a roller coaster and can still feel vertigo in your belly. But “Shadow” is so masterful during its wilder sections that a bit of tedium eventually seems a rather small price to pay. Zhang’s action is so magnificently imagined—not just in the bigger, more brazen touches, but in grace notes, like the way a weapon’s gory blade grinds as it’s dragged over rainy cobblestones, trailing plumes of muck and blood—that it shames the current industry norm as expressed in Marvel and DC films and most action thrillers post-Jason Bourne, which consist mainly of swinging the camera around and cutting as fast as possible, often (it seems) to disguise the fact that the performers aren’t all that graceful, and the director doesn’t really have a style, just money.

Zhang’s best work here is old-school craft, practiced with the latest filmmaking equipment and processes. The movie knows not just what do to technically, but how to make it resonate with the story and themes, and how to make images sing and dance. In a time of diminished expectations for big screen spectacle, and “content” replacing cinema, it takes a master to remind us of what’s been lost.

____________________

Watch Shadow on Tubi here: https://tubitv.com/movies/649980/shadow