From CollectiveUnconsciousFilm.com:

A man and his grandmother hide out from an ominous broadcast. A suicidal Grim Reaper hosts a children’s TV show. The formerly incarcerated remember and reinterpret their first days of freedom. A suburban mom’s life is upturned by the beast growing inside of her. And a high school gym teacher runs drills from inside a dormant volcano.

Welcome to collective:unconscious, a new collaborative feature in which five of independent film’s most adventurous and acclaimed filmmakers join forces to adapt each other’s dreams for the screen.

Featuring new work by Lily Baldwin (Sleepover LA), Frances Bodomo (Afronauts), Daniel Patrick Carbone (Hide Your Smiling Faces), Josephine Decker (Thou Wast Mild and Lovely), and Lauren Wolkstein (The Strange Ones), collective:unconscious pushes at the boundaries of narrative and surrealism, inviting viewers to immerse themselves inside a literal dream state. It’s “like nothing you’ve ever seen with your eyes open.” (Rolling Stone).

By Steve Johnson

Source: Bright Lights

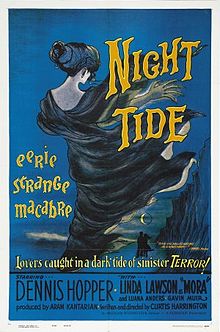

The first shot proper in Curtis Harrington’s 1961 feature film debut, Night Tide, situates main character Johnny Drake leaning over a pier in his sailor gear, slightly off-angle, so we understand that there’s something unresolved in his character, something at un-rest. The setting is Venice, California, a long way off from the Poe-like submerged city it’s named for, as are many of the film’s characters from their similar sources. A clairvoyant later calls Johnny innocent and searching, and everything about the moody composition reinforces this notion as he gazes into the reflective waters. There at the brink between land and sea, consciousness and dream, he’s Narcissus regarding himself in the pool, much like the protagonist of Harrington’s attention-getting 1946 short Fragment of Seeking.

In that earlier, experimental film, Harrington’s character — played by the director himself — pursues a robed figure after the fashion of Maya Deren’s “Meshes of the Afternoon,” only to discover that what he had taken to be a woman is instead himself, in drag. (The scenario is a gloss on such Poe tales as “William Wilson” and “The Assignation”; Harrington’s first short was an adaptation of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” a new version of which was also his final film work.) This motif of inquiring into gender and the self is revisited in film after film of Harrington’s no matter how personal or indifferent, from the exploration of the twin-gendered Venus and Mars of his next feature, Queen of Blood, through the various pursuits of his ’70s TV movies The Dead Don’t Die and How Awful About Allan, the latter climaxing in the reverse-unmasking of the lead’s veiled malefactor — whom he had assumed was a male boarder — as in fact his own sister.

This lunar pull toward some split-off aspect of the self is part allegorical, part autobiographical. In Night Tide, the division in Johnny’s object of fascination, the sideshow mermaid named Mora who believes she’s the real thing, represents our peculiarly human nature, being not entirely animal yet not entirely separate, either. In both evolutionary and individually developmental terms, she recalls the amniotic origins Johnny contemplates from his privileged perspective at the start of the picture, which viewpoint the film reiterates at other key points and in other key locations. That tension between our innocent beginnings and present “fallen” state reflects the director’s own attitude toward his ambitions and the course his career would take in the baroque and carnivalesque Hollywood where he found himself working for the next 25 years after this self-written and -financed calling card of a film.

Though Harrington’s character, and indeed the tone of his feature, is naïve, Harrington himself was not. True to the Hollywood Babylon of friend and early co-conspirator Kenneth Anger’s series of infamous industry exposés, the portrait of that town in such later Harringtons as What’s the Matter with Helen? maintains the grime on the city’s underbelly. For the novice filmmaker, Tinseltown was the Mora-like Lorelei whose song lured many a hapless romantic to his ruin. As his career lost its way from the wide-eyed optimism on display here, it bent itself to an increasing sordidness, the decadence that underlay his scenarios become less and less berobed with the illusion of glamor. By the time of his penultimate theatrical feature, the Exorcist knockoff Ruby, the putative Golden Age apostrophized throughout his work in the casting of mostly played-out Hollywood luminaries was at last seen as a nest of gangsters reduced to working for the title singer at her drive-in theater, her daughter the innocent supernatural woman of Night Tide become the actual agent of the violent deaths of which Mora, in her film, is falsely accused.

In conversation with David Del Valle on the latter’s cable interview program, The Sinister Image, Harrington described his first studio film, Games, as concerning the seeping of “European decadence” into innocent America. In that film, Night Tide‘s boardwalk attractions are literally internalized in the pinball-filled apartment and juvenile, prank-prone relationship of its socialite couple — based on Night Tide star Dennis Hopper and his Hollywood-royalty wife, Brooke Hayward — all of which turn malevolent under the influence of a French mystic played by Simone Signoret. In Night Tide this figure appears in the form of the Greek-speaking Mystery Woman (played by Marjorie Cameron, a consort of reputed Black Arts practitioner Aleister Crowley) and in Queen of Blood the vampiric cod-European extraterrestrial; in later tele-films The Dead Don’t Die it’s the zombie leader Varek, Killer Bees‘ queen-bee Madame von Bohlen, and the witchy Martine Beswick character of Devil Dog: Hound of Hell, as well as the soigné Nazi psychologist of theatrical career-closer Mata Hari.

Which is not to say that this influence need necessarily be European. The director just as easily gave it a domestic face in the form of Helen‘s radio evangelist played by Agnes Moorehead and her disturbed disciple Shelley Winters, and The Killing Kind‘s mother, Ann Sothern — symbols of Golden Age Hollywood, all, as was Bees‘ Gloria Swanson. The decadence, if any, is organic to its milieu; if it hails from any Old World to speak of, it’s a world within.

Harrington has said that all of his films are tragedies. Night Tide, at least, ends hopefully. When Ellen Sands, the land girl who vies for his affections, sees Johnny off, the implication is that she’ll be a soft place for him to land when he comes down from his guilty obsession over Mora; her offer of coffee on his way out is as Ariadne’s gift to Theseus of the thread of consciousness that would lead him out of the minotaur maze. With the more exotic love of Mora suggesting the primitive, deep and unfathomable artistic nature (she being first encountered in a subterranean jazz club and later doing an improvisational dance to a bongo beat) that Harrington would leave behind in the pursuit of bigger budgets, greater technical resources, and a wider audience, Ellen’s boardwalk merry-go-round suggests the simple, commercial (if mechanical) pleasures of an “innocent,” old-fashioned entertainment, and Night Tide the chronicle of a passage from avant-garde mother to the feature-length mainstream cinema Harrington would spend a quarter of a century courting with varying degrees of success.

We take solace in Johnny’s being escorted out by the Shore Patrol, suggesting that the questing sailor has found his feet and will one day return to the merry-go-round girl. It’s an odd early endorsement of heterosexual love and normality for a director the overwhelming bulk of whose later work describes such relations and their familial expression in grotesque terms — the undead marathon dancers of The Dead Don’t Die, the forced rape-participation of The Killing Kind, the suburban kennel that is Devil Dog‘s home and family (with its figurative “breeders”), as the ancestral-home hive of Bees. It’s no surprise, then, that the further Harrington came from the hopes of establishing the kind of career he may have envisioned, the harsher the satire became, until the disaster of the attempted Sylvia Kristel vehicle Mata Hari crumbled under the weight of its disinterest in the softcore couplings that were its generic reason for being. Afterward, it was series television for him, the likes of which — Dynasty, primarily — offered a more comfortable haven for his outright cynical — no longer conflicted — attitudes. It was as if Johnny had returned to find Ellen had given up the wait for him and gone. All that was left now was to join the amusements.

In 2022, an EMP detonation has caused a global blackout that has massive, destructive implications all over the world. Directed by Cowboy Bebop and Samurai Champloo’s Shinichiro Watanabe, Blade Runner Black Out 2022 is a new animated short which serves as a prologue for the feature film Blade Runner 2049.

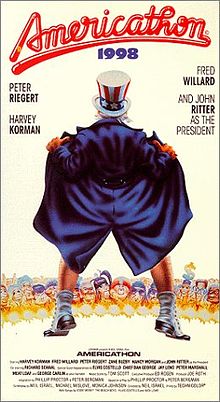

“Americathon” (1978) is, like Idiocracy, a dystopian comedy with prophetic predictions such as the fall of the USSR, privatization of public assets, smoking being banned, masses of homeless people living in cars, and the dominance of reality TV, but set in the then future year of 1998. It was directed by Neal Israel, based on a play by Firesign Theatre alumni Phil Proctor and Peter Bergman with narration by George Carlin. In Americathon’s vision of the future, the U.S. has passed peak oil and the government is on the brink of bankruptcy. In order to avoid having the country foreclosed and repossessed by the original owners, president Chet Roosevelt (John Ritter) organizes a national telethon with hilarious results. Features surprising appearances by Elvis Costello, Meat Loaf, Cybill Shepherd and Howard Hesseman.

Watch the full film here.

INDIAN COUNTRY NEWS

"It is the duty of every man, as far as his ability extends, to detect and expose delusion and error"..Thomas Paine

Human in Algorithms

From the Roof Top

I See This

blog of the post capitalist transition.. Read or download the novel here + latest relevant posts

अध्ययन-अनुसन्धानको सार