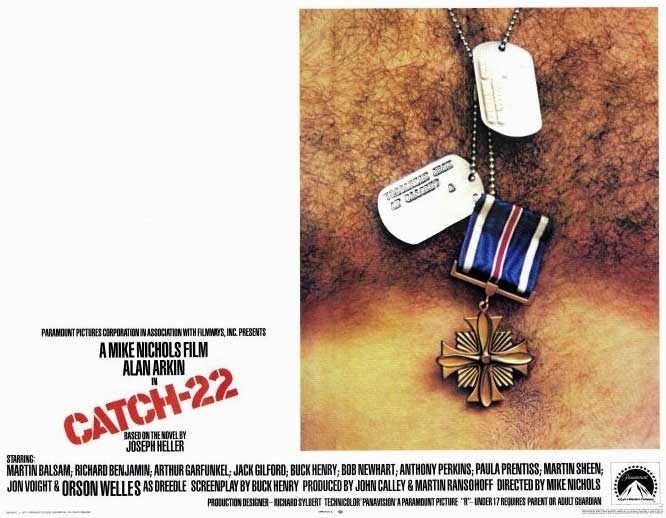

Classic Film Review: So was “Catch-22” the failure we remember it to be?

By Roger Moore

Source: Movie Nation

Perhaps it took a humorless, career-crippling George Clooney TV version of Joseph Heller’s novel to make us better appreciate Mike Nichols’ daring, infamously-expensive version of “Catch-22.”

Released at the height of the Vietnam War, suffering in comparison to Robert Altman’s equally anti-war dramedy “M*A*S*H,” seemingly more on a par with with equally cynical action comedy “Kelly’s Heroes,” which has had the benefit of a lot more TV exposure, “Catch” still plays the way it did way back in 1970 — as a pricey, “difficult” satire with a “difficult” shoot as baggage.

But wipe away the “Catch-22 lore,”the people cast and cast-aside, the fact that Nichols wanted the more age-appropriate Al Pacino as Yossarian, the young bombardier/anti-hero, and grapple with the film’s disordered narrative, the nightmarish focus of the story — an active-duty combat airman flying through and ranting through what we now call Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, coupled with a tinge of guilt.

It’s amazing to see now. And considering how our war movies, from “300” to “Midway,” “Greyhound” to “Flyboys” and even at times, “Dunkirk,” are made now — with digital planes and ships and sometimes tanks — they really don’t make’em like this any more.

Nichols made the most of his coastal Mexican location, showing off all 17 WWII vintage B-25s taking off and landing every chance he got. You couldn’t do that today.

And that cast. Alan Arkin makes a fine, perplexed and outraged Yossarian, a sane man trapped in the insanity of war, an actor who never hits a punchline too hard, never takes the character’s exasperation into parody.

“Let me see if I’ve got this straight. In order to be grounded, I’ve got to be crazy. And I must be crazy to keep flying. But if I ask to be grounded, that means I’m not crazy anymore, and I have to keep flying.”

“You got it,” Doc Daneeka (Jack Gilford) tells him. “That’s Catch-22.

“Whoo… That’s some catch, that Catch-22.”

Orson Welles as a grumpy general, Tony Perkins as a put-upon chaplain, Martin Balsam as the murderously vain Col. Cathcart, Buck Henry as his venal sidekick, Col. Corn (screenwriter Henry was never better, as an actor), baby-faced Bob Balaban as the always-crashing, always-tinkering, even-tempered Orr, it’s a dazzling corps.

Bob Newhart half-stammering through Major Major Major, a very young Martin Sheen raging as the pilot Dobbs, Art Garfunkel as the innocent co-pilot Nately who falls for an Italian hooker, Charles Grodin as an upper-class twit navigator, a smarmy, befuddlingly upbeat Richard Benjamin (cast, with his wife Paula Prentiss as a nurse Yossarian chases), the famous French star who fled to Hollywood Marcel Dalio is the wizened old Italian who figures Italy has already won the war, since it has surrendered and Americans are still fighting and dying. And there’s a sea of actors we’d come to recognize on TV (“The Bob Newhart Show” is over-represented) in the years that followed.

Jon Voight stands out, just enough, as the grinning opportunist Milo Minderbender, a stand-in for every war profiteer you’ve ever read about, working the angles, an impersonal unpatriotic multinational corporation who wins no matter who loses.

Like its two contemporaries, “M*A*S*H” and “Kelly’s Heroes,” it’s a guy’s movie with a dated leering quality about the opposite sex. It’s heavy-handed, here and there, betraying Nichols — feeling his oats after “The Graduate” — indulging in some serious “blank check” filmmaking.

And reading, over the years, of all the people Nichols wanted to cast, or cast and then replaced, you kind of wish he’d moved on from Gilford, a future Oscar nominee who doesn’t bring enough cowardly sniveling to the good doc.

“Catch-22” was popular enough that they did a pilot for a sitcom based on it, as was the case with “M*A*S*H.” Richard Dreyfuss had the lead in that.

Over the years, I’ve interviewed half a dozen actors from that all-star cast, and often, without prompting, they’d bring it up. It took half a year of their lives, most of them, and burned itself into their memories, even if it wasn’t the blockbuster Paramount expected it to be.

Watching it again, outside of the academic settings where it turned up in “film as satire” classes and the like, it feels more cinematic than the scruffy, Altmanesque “M*A*S*H,” a movie marred by that stupid screen-time-chewing football game. It’s less fun than the more-watchable “Patton” and even “Kelly’s Heroes” (which is FAR longer).

But as a darker-than-dark comedy about the futility and insanity of war, it towers above its contemporaries in ways that should have scared-off George Clooney. It’s the best film of a seemingly-unfilmmable classic novel we’re ever going to get.

MPAA Rating: R, graphic violence, blood, nudity, profanity

Cast: Alan Arkin, Martin Balsam, Buck Henry, Tony Perkins, Bob Newhart, Paula Prentiss, Richard Benjamin, Marcel Dalio, Bob Balaban, Art Garfunkel, Martin Sheen, Jack Gilford, Peter Bonerz, Norman Fell, Austin Pendleton, Jon Voight and Orson Welles.

Credits: Directed by Mike Nichols, script by Buck Henry, based on the Joseph Heller novel. A Paramount release.

Running time: 2:02

____________________

Watch Catch-22 on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/3216674