By Rob Gonsalves

Source: Rob’s Movie Vault

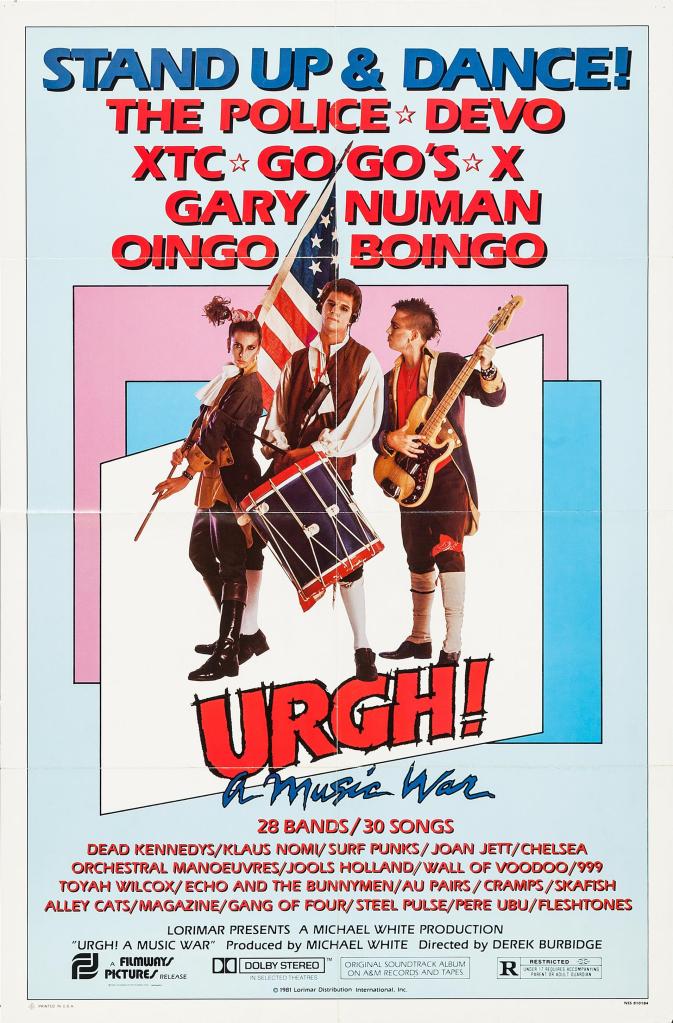

I loved every second of Urgh! A Music War, even when I was baffled. Perhaps especially when I was baffled. How else does one respond to such only-in-the-early-’80s acts as Invisible Sex, who appear onstage in makeshift hazmat suits, or the late Klaus Nomi with his futuro-bizarro getup and his soaring falsetto, or the Surf Punks with their punk-nerd outfits and the simulated sex in an onstage beach shack? Dear God, what a strange and wondrous time for alternative music. This was an era in which the Go-Gos could be sandwiched between the roughhouse punk acts Athletico Spizz 80 and Dead Kennedys and somehow not seem out of place. (Belinda Carlisle, in the Urgh! footage, may be bouncy and happy, but she’s got the prerequisite short punk ‘do.)

Urgh! was filmed in 1980 at a variety of locations (New York, London, France, Los Angeles) as a somewhat scattershot attempt to capture some of the emerging New Wave and punk acts of the day. It can be seen today as an accidental Woodstock, as musically important in its way as Michael Wadleigh’s Oscar-winning documentary was. It catches, for instance, one of XTC’s last live performances (a ripsnorting “Respectable Street,” easily one of the film’s highlights) before Andy Partridge got allergic to the stage life and announced that XTC would no longer do concerts. At the end, when the Police do “Roxanne” (a great performance — man, they kicked ass in concert back in the day) and then “So Lonely,” they invite various groups we’ve seen in the movie: UB40, Skafish, the ivory-tickling Jools Holland, and others; it’s a semi-historic jam.

When the camera moves in on one attractive woman or another in the crowd (which is somewhat often), you can tell that at the time the camera crew was just filming whatever caught their eye (and pants), but seen today it’s a cultural document: It’s fun to see how young women were dressing to go see X or Pere Ubu. From this movie, you might also conclude that the Lollapalooza generation didn’t invent pogo-ing, moshing, and stage-diving; you see it all here (most amusingly, I thought, during sets by the Go-Gos and Oingo Boingo). Urgh! also captures a deadpan-antagonistic time in rock. Many of the punk and New Wave acts here don’t seem to give a fuck whether you like them or not, yet they come to play and they play hard. When Lux Interior of the Cramps sticks his mike in his mouth and staggers around grunting as it hangs out, it’s a primal moment to rival Pete Townshend’s guitar-smashing; it comes from the same basic impulse, anyway.

You notice, too, the high level of joy in these performances. Many of the arrogant young (mostly) men onstage may have been in it to entertain themselves, but they keep things moving. The gyrations here couldn’t be further from the frozen-faced growling of today’s “alternative” rock. Dead Kennedys’ frontman Jello Biafra, spitting out “Bleed for Me,” exhorts the crowd to enjoy the freedom to hear punk rock — while it lasts (the punk rock and the freedom). Biafra has a corrosive staccato gaiety that matches Johnny Rotten at his most splenetic. Kenneth Spiers, lead shouter of Athletico Spizz 80 (doing their novelty hit “Where’s Captain Kirk?”), jumps around spraying the audience, fellow band members, and himself with silly string, then tosses the empty can over his shoulder, not caring if it hits any of his bandmates. Jim Skafish bends himself into art-rock pretzels during “Sign of the Cross,” a nerd’s idea of punk (a lot of the music here is a nerd’s idea of punk, including Devo, represented here with the relentless “Uncontrollable Urge”). Steel Pulse illustrate their song “Ku Klux Klan” with a (black) band member capering onstage in a KKK outfit. Howard Devoto of Magazine — the former Buzzcocks member who bears an uncanny resemblance to Chuck & Buck‘s Mike White — strolls around the stage as if waiting for a bus, a sly inversion of punk flailing that has its own quiet punk wit. In comparison with the carefree showmanship seen in Urgh!, many of today’s acts seem stoic, almost monastic, and far more self-involved and nihilistic than the most insular New Wave warbler.

Half of these groups didn’t seem to go anywhere after 1981, but it’s a treat to go back in time and catch the ones that did make it. Two elder statesmen of film-soundtrack composition, Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo and Danny Elfman of Oingo Boingo, come off here like the sweaty madmen they were back then. Joan Jett (doing an electrifying “Bad Reputation”) looks appealingly almost-chubby, before the label presumably told her to slim down for MTV; the same is true of Belinda Carlisle. Exene Cervenka nonchalantly commands the stage on X’s “Beyond and Back,” as does Gary Numan (tooling around in a little car) on “Down in the Park.” The one-hit wonders and no-hit wonders are equally alluring. I was charmed by Toyah Willcox’s jubilant hopping about, trying to be cool but too happy to pull it off. It’s a shame the exuberant Chelsea weren’t better known. Wall of Voodoo, whose lead singer Stan Ridgway resembles a crank-addled Griffin Dunne, pumps up the defiant “Back in Flesh” (no, not “Mexican Radio” — that would be too obvious). The movie is heavily male, but the female singers — Willcox, Carlisle, Jett — distinguish themselves by their clarity. Joan Jett screams as fiercely as anyone, but you can understand everything she’s saying, whereas many of the male singers rant unintelligibly (which can be its own kind of hostile fuck-you lyricism). The viewer/listener comes away thinking that Jett and the other women have fought too hard to be on that stage to waste the opportunity to be heard; the men, accustomed to being heard, let their words clatter and fall every which way.

Jonathan Demme is thanked in the credits, and much of Urgh! shares the concert-film aesthetic he pioneered in Stop Making Sense and continued in Storefront Hitchcock. Director Derek Burbidge, who made rock videos back then (including “Cars” for Gary Numan and pretty much all the Police’s early MTV highlights), is into simplicity, not flash (a useful approach when catching thirty-odd bands on the fly in three different countries). The bands are given space to work up their own rhythm — the editing doesn’t do it for them. Burbidge is as fond of the mammoth close-up as Sergio Leone ever was, and half of “Roxanne” seems to explore Sting’s nostrils from previously unseen angles. Performers like Lux Interior and Jello Biafra seem to be dripping sweat right onto you. The effect is to take you into the front row.

Urgh! doesn’t (and can’t possibly) have the cohesive brilliance or musical momentum of Stop Making Sense — the styles are simply too varied, throwing you from catatonic New Wave to thrashing punk in an eyeblink. Still, as a record of a moment and a sound, it ranks up there with the best you’ve seen and heard.