Author Archives: Reid Mukai

Saturday Matinee: From Hell

By Roger Ebert

Source: RogerEbert.com

One day men will say I gave birth to the 20th century. — Dialogue by Jack the Ripper I’ d like to think Darwin has a better case, but I see what he means. The century was indeed a stage for the dark impulses of the soul, and recently I’ve begun to wonder if Jack didn’t give birth to the 21st century, too. Twins. During 10 weeks in autumn 1888, a serial killer murdered five prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London. The murders were linked because the Ripper left a trademark, surgically assaulting the corpses in a particularly gruesome way. “I look for someone with a thorough knowledge of human anatomy,” says Inspector Abberline of Scotland Yard. An elementary knowledge would have been sufficient.

The story of Jack the Ripper has been fodder for countless movies and books, and even periodic reports that the mystery has been “solved” have failed to end our curiosity. Now comes “From Hell,” a rich, atmospheric film by the Hughes Brothers (“Menace II Society“), who call it a “ghetto film,” although knowledge of film, not the ghetto, is what qualifies them.

Johnny Depp stars as Inspector Frederick Abberline, an opium addict whose smoke-fueled dreams produce psychic insights into crime. The echo of Sherlock Holmes, another devotee of the pipe, is unmistakable, and “From Hell” supplies its hero with a Watsonoid sidekick in Peter Godley (Robbie Coltrane), a policeman assigned to haul Abberline out of the dens, gently remind him of his duty, protect him from harm, and marvel at his insights. Depp plays his role as very, very subtle comedy–so droll he hopes we think he’s serious.

The movie feels dark, clammy and exhilarating–it’s like belonging to a secret club where you can have a lot of fun but might get into trouble. There’s one extraordinary shot that begins with the London skyline, pans down past towers and steam trains, and plunges into a subterranean crypt where a Masonic lodge is sitting in judgment on one of its members. You get the notion of the robust physical progress of Victoria’s metropolis, and the secret workings of the Establishment. At a time when public morality was strict and unbending, private misbehavior was a boom industry. Many, perhaps most, rich and pious men engaged in private debauchery.

The Hughes Brothers plunge into this world, so far from their native Detroit, with the joy of tourists who have been reading up for years. Their source is a 500-page graphic novel (i.e., transcendent comic book) by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell, and some of their compositions look influenced by comic art, with its sharp obliques and exaggerated perspectives. The movie was shot on location with the medieval streets of Prague doubling for London, and production designer Martin Childs goes for lurid settings, saturated colors, deep shadows, a city of secret places protected by power and corruption.

We meet some of the prostitutes, particularly Mary Kelly (Heather Graham), who is trying to help her sisters escape from the dominance of the pimps. We see Abberline and Kelly begin a romance that probably would have been a lot more direct and uncomplicated at that time than it is in this movie. We see members of Victoria’s immediate family implicated in whoring and venereal mishaps, and we meet the Queen’s Surgeon, a precise and, by his own admission, brilliant man named Sir William Gull (Ian Holm). The investigation is interrupted from time to time by more murders, graphically indicated, and by forms of official murder, like lobotomy. Sir William is an especially enthusiastic advocate of that procedure, reinforcing my notion that every surgeon of any intelligence who practiced lobotomy did so with certain doubts about its wisdom, and certain stirrings of curious satisfaction.

Watching the film, I was surprised how consistently it surprised me. It’s a movie “catering to no clear demographic,” Variety reports in its review, as if catering to a demographic would be a good thing for a movie to do. Despite its gothic look, “From Hell” is not in the Hammer horror genre. Despite its Sherlockian hero, it’s not a Holmes and Watson story. Despite its murders, it’s not a slasher film. What it is, I think, is a Guignol about a cross-section of a thoroughly rotten society, corrupted from the top down. The Ripper murders cut through layers of social class designed to insulate the sinners from the results of their sins.

Two for Tuesday

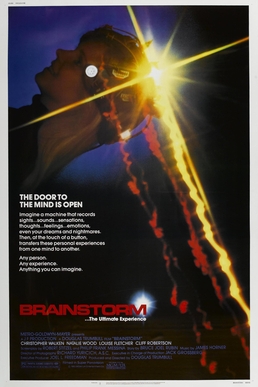

Saturday Matinee: Brainstorm

By Moe

Source: Cup of Moe

The 1983 sci-fi thriller “Brainstorm” stars Christopher Walken and Natalie Wood. This forward-thinking science fiction romp presents virtual reality (VR) in its early stages and evolution. Although the Douglas Trumbull-directed film isn’t perfect, it’s a neat look at VR with superb acting, a magnificent score, and excellent effects.

A scientific group led by Michael Brace (Walken) and his estranged wife Karen (Natalie Wood), along with Michael’s colleague Lillian (Louise Fletcher) invents the computer and brain interfacing device. Their creation not only allows for virtual reality experiences but allows feelings and sensations to be recorded on tape. In this way, others may experience those as well.

After their initial success, CEO Alex Terson (Cliff Robertson) instructs Brace et al to offer a demo of their device with the intent to secure financial backing. It’s during this exhibition that the group realizes the true power of their device: its ability to record human emotions. Michael uses the device to record memories with emotions, and thereby influence the real world. But whereas Michael employs this as the utility to reconnect with his estranged wife, previous colleague Landan Marks (Donald Hotton) aspires to use it for military applications.

When Lillian suffers a heart attack, she puts on the headset and records her death. Michael later discovers her recorded memories. Eventually, Michael realizes the insidious intent to use his creation for warfare when he uncovers “Project Brainstorm.” As such, Michael and Karen team up to thwart efforts to use their technology to perpetuate the military industrial complex.

“Brainstorm” offers an intriguing and groundbreaking look at VR. There’s an exploration of not only virtual reality experiences but the effects on the user. This manifests in the ability to record emotions as well as memories. I like the way “Brainstorm” touches on humanity’s influence of tech, and the means through which tech shapes humanity. Moreover, “Brainstorm” presents an accurate portrayal of tech advancement. Early in the film, Terson instructs his team to make a smaller version of their helmet. Similarly, a trend in real-world technology is constant innovation in creating smaller devices.

I quite enjoy the helmet design and the effects are top-notch. The 1983 movie has aged pretty well with its fish-eye lens shots and well-crafted animation sequences.Trumbull worked on effects for films such as “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Silent Running,” and “Blade Runner.” It’s evident that Trumbull understood the genre and he infuses mesmerizing special effects, particularly at the end.

Cinematography is fantastic. The film is set in North Carolina and uses several NC scenes as prominent backdrops. Notably, the Wright Brothers National Memorial plays an important role. Plus, there’s a neat shot of Duke Chapel. Locations even appear futuristic. The Burroughs Wellcome building offers its then high-tech looks as the main office for Michael, Karen, and Lillian. A gorgeous Chapel Hill, NC home with its parallelogram angles and solar panels was used as well.

Acting is phenomenal. Walken lends an inspired performance, and Natalie Wood is captivating in her final cinematic appearance. But it’s Louise Fletcher as Lillian who completely steals the show with a tour de force acting job.

It would be remiss to discuss “Brainstorm” without touching on its superb score. Renowned composer James Horner provides the musical backing which is replete with the timpani Horner became best known for. Horner’s “Brainstorm” soundtrack features elements from his “Wolfen” score. Later, in the 1986 sci-fi hit “Aliens,” Horner continued this trend. But it’s a formula that works.

Unfortunately, “Brainstorm” doesn’t quite end as well as it starts. The finale is admittedly a muddled moment which will leave you wondering “what?” as the credits roll. Michael plays back Lillian’s tape and watches the afterlife playing out, even glimpsing hell for a moment. Departed souls in the form of bioluminescent butterflies flow peacefully into heaven. Though the effects hold up fine, this sequence falls flat in lacking the poetry of similar scenes like the end of “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Still, it’s tough to hold the abrupt and admittedly cheesy, ending against the movie. Wood’s tragic and mysterious death led production to halt. Eventually, Trumbull rewrote the script and used Wood’s younger sister as a stand-in for her remaining shots.

I especially enjoy how “Brainstorm” probes the relationship between tech and humanity, presenting complex concepts like computer-brain transference. “Brainstorm” may not carry the legacy of sci-fi flicks like “Blade Runner,” “Alien,” and “The Matrix.” However, its stellar cinematography, acting, score, and effects plus forward-thinking portrayal of tech make this 1983 movie a smart, lasting thriller.

Two for Tuesday

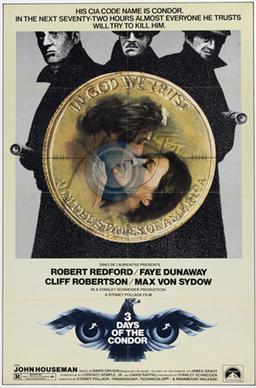

Saturday Matinee: Three Days of the Condor

Three Days of the Condor

A thriller for thinkers probing covert activities within the CIA.

By Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

Source: Spirituality & Practice

Joseph Turner — code name Condor — works at the American Literary Historical Society in New York City. The organization is actually a branch office of the CIA. He and his youthful coworkers read, analyze, and computerize various spy stories, mysteries, and periodicals for the CIA’s mammoth intelligence gathering operations.

One rainy day while Turner is out to lunch, the rest of the staff is brutally murdered. Scared out of his wits, he contacts the CIA and is told to go into hiding. When he does arrange a meeting with the CIA, he is fired upon and his best friend, along to help identify the contact, is shot by another agent. Terror grips Turner. He abducts Kathy Hale, a photographer, and in her apartment in Brooklyn tries to unravel the mysteries surrounding the executions.

Three Days at the Condor works on two levels: as an examination of the covert activities within the CIA and as a somewhat curious look at the development of a relationship through shared stress. Robert Redford is just right as the paranoid Turner, a bright young man unexplainably put in a harrowing situation. Did the slaughter of the American Literary Historical Society staff stem from his inquiry to CIA headquarters about a mystery novel only translated into Dutch and Arabic? Perhaps someone in higher places was doing unauthorized intelligence work and Turner stumbled onto his scheme. Can Turner now determine who’s out to silence him? Director Sydney Pollack, (The Way We Were, Yakuza) orchestrates the zigzag storyline into a labyrinth of effective scenes, revealing Turner’s fright and his own special brand of grace under pressure.

Faye Dunaway gives a well modulated performance as the woman who is kidnapped by Turner at gunpoint and forced to serve as his host. Her initial fright turns to anger as he brutalizes her. But then, through the bizarre intermix of their wants and needs, the two develop an uneasy relationship. Sex is one part of the bond drawing them together; intelligence the other. She helps him solve the mystery and come to terms with his conscience. He helps her to a new understanding of her loneliness. Faye Dunaway, moving from her standout role in Chinatown to this notable performance, proves that she is one of our better actresses.

Also featured in this gripping suspense story are Cliff Robertson and John Houseman as two Central Intelligence Agency officials and Max Von Sydow as a hit man used by the CIA on various contacts. In the wake of Watergate and the recent probes on the CIA, Three Days of the Condor has a resonance with the general mood of public uneasiness about secrecy in high places. We can empathize with these characters and their paranoia. Although it doesn’t really make any sophisticated political commentary on the activities of the CIA, this movie does work as a thriller for thinkers.

Watch Three Days at the Condor here: https://m.ok.ru/video/9819443366575

Two for Tuesday

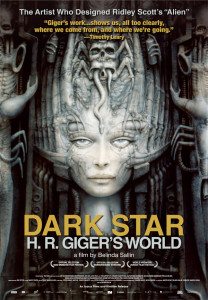

Saturday Matinee: Dark Star: H. R. Giger’s World

Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World, In Which The Alien Artist Is Examined

By Supreme Being

Source: Stand By for Mind Control

H.R. Giger, who most famously created the monster design for Alien (and less famously, prior to that, artwork for Jodorowsky’s never-made Dune adaptation), is a pleasant old man at the end of his life in the new documentary, Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World, much of which follows Giger, his wife, and friends puttering around his cluttered home of many years.

Dark Star is a nicely puttering little movie, refreshingly unlike so many modern docs, those that consist largely of talking heads speedily edited together with rapid-fire clips, so as not to bore audiences. Defensive movie-making, this is called. It’s assumed documentaries bore people, so they’re now edited as jauntily as possible, to keep things moving. Dark Star has very few people sitting down for proper interviews. There are a few, scattered throughout, but they’re not there to relate Giger’s history. Instead they talk about him as a man and as an artist, or talk about his art, or about how he and his artwork affected their lives.

No chronological story is told here. A certain amount of old footage is included of Giger as a younger man, but there’s no narration over it. It’s more that Dark Star, a Swiss production directed by Belinda Sallin, gives an impression of Giger’s life and work, and does so in a gently paced, meandering way. Which style I liked quite a bit. By its nature it was slow to grow on me, but the more I watched, the more the picture was filled in, and the more I became absorbed in it.

At one point I began wishing they’d just show more of his artwork up close, instead of showing shaky shots of it hanging on the walls of his house—and almost as if reading my mind, the movie went into a section showing off his artwork. Well played, Dark Star, well played.

Giger’s art is generally described as being “biomechanoid,” or some other made up word like that. One thing’s for sure: it’s unique. Nobody paints like Giger. Once you’ve seen anything he’s done, and you have, because you love Alien and like me have watched it 500 times, his work, any of it, is instantly recognizeable. It’s all women and bones and machines and warped little children, birth and sex and death, all in the same painting, all happening at the same time.

Well. I’m not going to try to describe his art. Look for yourself. Whatever, exactly, it is, it sticks its fingers deep inside the human psyche and wriggles them around.

A small part of the movie focuses on Alien, with some nice footage of Giger constructing the space-jockey set, and an old interview where he explains that his original alien egg opening—a slit—looked too much like a vagina. “This movie is going to play in Catholic countries,” he was told, so he had to make it less sexual. His solution? Two crossing slits, i.e., two vaginas in the shape of a cross. Take that, Catholics!

There’s no mention of Giger’s earlier, unused work for Jodorowsky’s unrealized Dune project, but again, this isn’t a comprehensive look at Giger. It’s a meandering one. Eventually it meanders to a little Swiss town where Giger grew up. His mother, it turns out, was a huge supporter of his art, though initially Giger worried—as one might expect—about what reaction his parents would have to the things he painted.

Giger spent most the money his art brought in on still other creations. Like the kid-sized, haunted house-like train set in his backyard, which we get to ride around on. Also toward the end of his life, he participated in the creation of a Giger museum in Switzerland to house a large portion of his work, much of which he’d slowly bought back from collectors over the years. For the museum’s opening, Giger signs books and posters and body parts. One of his male fans pulls off his shirt and turns around to reveal his entire back tattooed with one of Giger’s images. “Very nice work,” mutters Giger. One tough-looking, tattooed young man has his art signed, shakes Giger’s hand, and walks away crying. Giger’s work had a profound effect on many people.

Giger died in 2014, shortly after the completion of Dark Star. He does look a bit like he’s near his end while being interviewed. He doesn’t have a lot to say. What comes across clearly is a man who’s satisfied with his work, who got to do exactly what he wanted, who didn’t feel he’d failed to accomplish anything he set out to accomplish.

Watch Dark Star: H. R. Giger’s World on tubi here: https://tubitv.com/movies/704843/dark-star-h-r-giger-s-world