By Sheila O’Malley

Source: RogerEbert.com

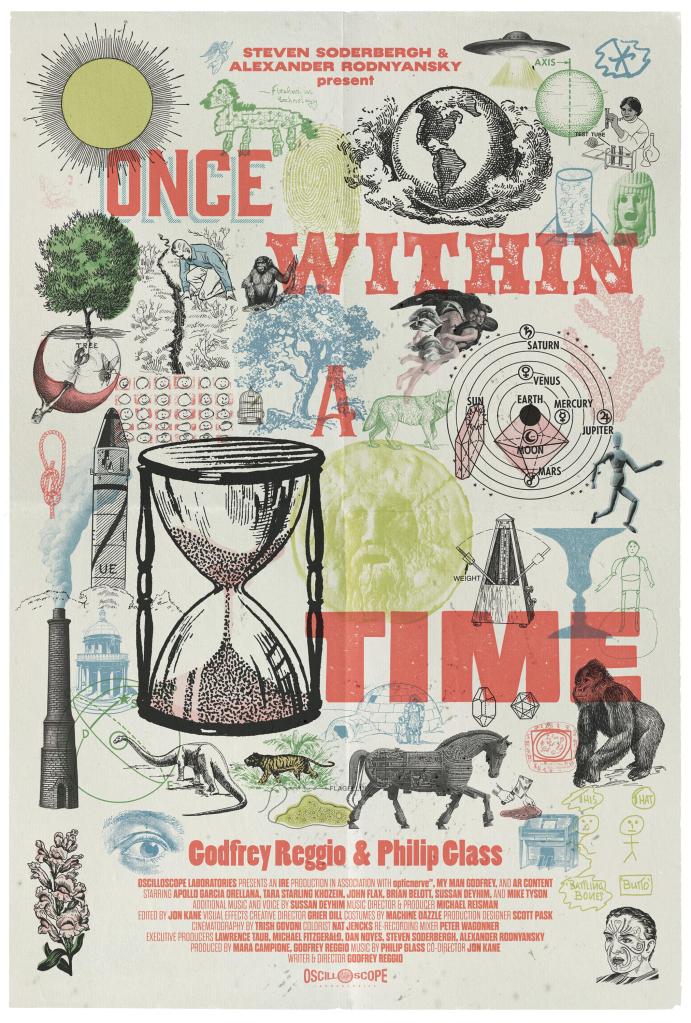

Beatrice Loayza’s fascinating New York Times article “When Did the Plot Become the Only Way to Judge a Movie?” examines films that eschew linear storytelling, films more interested in mood and emotional tones than plot points, breaking free from the “tyranny of story.” The article was fresh in my mind when I watched Godfrey Reggio’s whimsical-terrifying doomsday-fable “Once Within a Time.” Clocking in at 51 minutes, the film is all mood, all rhythm, with a kaleidoscope structure and undulating ever-shifting visuals in a constant state of flux. It’s not a “story” so much as a tone-poem collage about technology, knowledge, innocence/experience, and the potential end of the world. Maybe something new will be born from the ashes, although considering the evidence that something may very well be a monster.

It all started in the Garden of Eden, when curious Eve ate the apple, and “Once Within a Time” starts there, too, in the gentle framing device that opens it. An audience sits in a darkened theatre, a red velvet curtain rises, and the “show”—i.e., human life on the spinning planet—begins. Adam and Eve, holding hands, wander underneath a white cotton-ball tree with red hanging apples. Around them, children play and cavort. The same six or seven children are used throughout: we get to know their faces and their expressions. Behind them, a grand visual drama unfolds, made up of stop-motion animation figures, real humans, found footage, and eerie created images: solar systems, a giant hourglass in the desert, black and white newsreel footage of bomb blasts, spindly trees bending backward. The children look on with wonder, humor, interest, and sometimes concern. They are trying to understand. The apple is a portal to another world, another time. The apple is also directly linked to another 20th-century apple, the Mac apple. The garden path Adam and Eve walk down is made up of iPhone cobble stones. The meaning is obvious.

Technology is a blessing and a curse, yes, but more than that, it’s inevitable. It can’t be stopped. Nineteen-year-old Mary Shelley wrote one of the most prescient books of all time, her imagination stretching forward 200 years, its warning message still and always relevant. The obsessed maniac Frankenstein doesn’t know when to stop with his experiment. He has to see it through, even if it destroys his mind, his life, and the world as we know it. Mary Shelley saw it all. “Once Within a Time” has almost as bleak an outlook.

Reggio’s celebrated “Koyaanisqatsi,” the first of the Qatsi Trilogy, features a similar cascade of images placed in fluid shifting juxtaposition: power plants and rain forests, rush-hour highways and crashing ocean, pollution and clouds, modernity and its ruins. The images are often beautiful, but the overall effect is anxiety-provoking, sometimes even despairing. What have we done to our beautiful world? Music holds it all together. Philip Glass composed the main score, with additional music by Iranian composer Sussan Deyhim (who also plays a “muse” type character, half-woman, half-tree).

Reggio’s vision has three central figures, symbolic and archetypal, but with shifting meanings. An opera maestro declaims his incomprehensible song to the masses, his figure a towering monolith, his eyes wild and fanatical. Behind him looms the walls of a Coliseum, and his figure is threatening, a demi-god dictator, gesturing and bending the masses to his will. There’s a female figure, a living half-human Yggdrasill (Sussan Deyhim), whose song helps create—or at least sustain—the living world. In the final segment, a “mentor” appears (Mike Tyson, of all people!), who encourages the cowed lost children, acting as a sort of Pied Piper.

Once you leave Eden, of course, you can’t get back in. That’s the deal. At the end of the film, a question is asked in multiple languages: “Which age is this: the sunset or the dawn?” In the atom-bomb-haunted “Rebel Without a Cause,” Plato (Sal Mineo) asks Jim (James Dean) if he thinks the end of the world will come at night. Jim says, “No. At dawn.” Either way, it’s the end.

Watch Once Within a Time on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/movie/once-within-a-time-mike-tyson/17458850