By Colin Marshall

Source: Open Culture

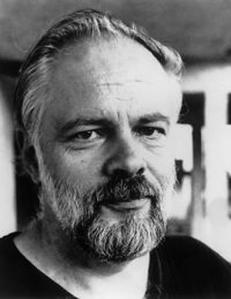

Philip K. Dick died in 1982, but readers — more readers than ever, in all probability — still thrill to his daring, unconventional imagination, and how tightly he could weave the inventions of that imagination into mundane reality. (Sometimes they wonder, as in his meeting with God, to what extent he himself could tell the two apart.) And like many strong-visioned writers of what roughly fell into the category of science fiction, Dick got consulted now and again as something of a futurist.

In 1980, David Wallechinsky, Amy Wallace, and Irving Wallace (the Book of Lists people) rounded up visions of the future from all manner of sages past and present, prescient and incompetent, in order to create The Book of Predictions. Dick’s contributions, republished in the September 2003 issue of fanzine PKD Otaku, go like this.

- 1983: The Soviet Union will develop an operational particle-beam accelerator, making missile attack against that country impossible. At the same time the U.S.S.R. will deploy this weapon as a satellite killer. The U.S. will turn, then, to nerve gas.

- 1984: The U.S. will perfect a system by which hydrogen, stored in metal hydrides, will serve as a fuel source, eliminating a need for oil.

- 1985: By or before this date there will be a titanic nuclear accident either in the U.S.S.R. or in the U.S., resulting in shutting down all nuclear power plants.

- 1986: Such satellites as HEAO-2 will uncover vast, unsuspected high energy phenomenon in the universe, indicating that there is sufficient mass to collapse the universe back when it has reached its expansion limit.

- 1989: The U.S. and the Soviet Union will agree to set up one vast metacomputer as a central source for information available to the entire world; this will be essential due to the huge amount of information coming into existence.

- 1993: An artificial life form will be created in a lab, probably in the U.S.S.R., thus reducing our interest in locating life forms on other planets.

- 1995: Computer use by ordinary citizens (already available in 1980) will transform the public from passive viewers of TV into mentally alert, highly trained, information-processing experts.

- 1997: The first closed-dome colonies will be successfully established on Luna and Mars. Through DNA modification, quasi-mutant humans will be created who can survive under non-Terran conditions, i.e., alien environments.

- 1998: The Soviet Union will test a propulsion drive that moves a starship at the velocity of light; a pilot ship will set out for Proxima Centaurus, soon to be followed by an American ship.

- 2000: An alien virus, brought back by an interplanetary ship, will decimate the population of Earth, but leave the colonies on Luna and Mars intact.

- 2012: Using tachyons (particles that move backward in time) as a carrier, the Soviet Union will attempt to alter the past with scientific information.

Cherry-pickers among us will fixate on Dick’s near-hits: the development of DNA modification, a 1985 nuclear accident in the U.S.S.R. (Chernobyl happened in 1986), and computer use by ordinary citizens (though our status as “mentally alert, highly trained, information-processing experts” admittedly remains questionable). Others might prefer to highlight the most improbable, such as the eliminated need for oil, the creation of artificial life, and not just the 21st-century existence but eventual time-traveling capabilities of the Soviet Union.

Still, even in his fiction, Dick does have his moments of prophecy, especially for those who share his paranoia that we’ve unwittingly let ourselves slip into surveillance-state conditions. But I’ve always found him best, especially in the what-if-Japan-won-the-war story The Man in the High Castle, as a teller of alternate histories, whether of the past, present, or future. These predictions, stretching from just after the writer’s death to just before our time, strike me as nothing so much as the premises for the best novel Philip K. Dick never wrote.

You can find 33 of his stories online here.

Related Content:

Philip K. Dick Takes You Inside His Life-Changing Mystical Experience

Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974)

33 Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books & Free eBooks

Philip K. Dick Previews Blade Runner: “The Impact of the Film is Going to be Overwhelming” (1981)

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today — in 2014

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.