By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

The banquet of consequences for the Fed, the elites and their armies of parasitic flunkies and factotums is being laid out, and there won’t be much choice in the seating.

Words can be debased just like currencies. Take the word sacrifice. The value of the original has been debased by trite, weepy overuse to the point of cliche. Like other manifestations of derealization and denormalization, this debasement is invisible, profound and ultimately devastating.

Consider the overworked slogan of implied shared sacrifice: we’re all in this together. Pardon my cynicism, but doesn’t this sound like what the first class passengers in the lifeboats shouted to the doomed steerage passengers on the sinking Titanic?

Here is the ice-cold reality of America in 2020: Sacrifice for Thee But None For Me. This isn’t a new trend, of course. Any measurable sacrifices shared by all the socio-economic classes ended with World War II in 1945, and since then it’s been one long slide to Sacrifice for Thee But None For Me.

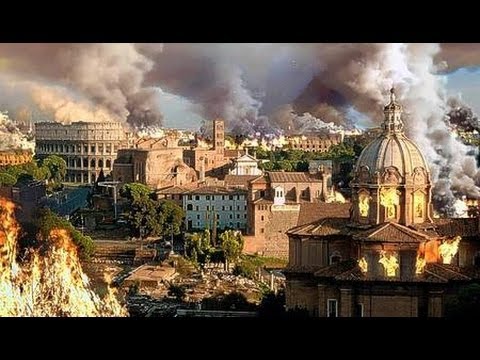

We’ve seen this slide to decay and collapse many times in history. The elites who once gained social status and political power by making real sacrifices on behalf of the nation / empire become entirely self-serving, accumulating ever greater wealth and power by transferring all the sacrifices and risks onto the lower classes.

Peter Turchin, author of War and Peace and War: The Rise and Fall of Empires, describes how civic virtue is gradually replaced by personal greed and self-interest.

This excerpt perfectly captures the current zeitgeist:

“Virtus included the ability to distinguish between good and evil and to act in ways that promoted good, and especially the common good. Unlike Greeks, Romans did not stress individual prowess, as exhibited by Homeric heroes or Olympic champions. The ideal of hero was one whose courage, wisdom, and self-sacrifice saved his country in time of peril.

Unlike the selfish elites of the later periods, the aristocracy of the early Republic did not spare its blood or treasure in the service of the common interest. When 50,000 Romans, a staggering one fifth of Rome’s total manpower, perished in the battle of Cannae, as mentioned previously, the senate lost almost one third of its membership. This suggests that the senatorial aristocracy was more likely to be killed in wars than the average citizen….

The wealthy classes were also the first to volunteer extra taxes when they were needed… A graduated scale was used in which the senators paid the most, followed by the knights, and then other citizens. In addition, officers and centurions (but not common soldiers!) served without pay, saving the state 20 percent of the legion’s payroll….

The richest 1 percent of the Romans during the early Republic was only 10 to 20 times as wealthy as an average Roman citizen.”

Now compare that to the situation in Late Antiquity when

“An average Roman noble of senatorial class had property valued in the neighborhood of 20,000 Roman pounds of gold. There was no ‘middle class’ comparable to the small landholders of the third century B.C.; the huge majority of the population was made up of landless peasants working land that belonged to nobles. These peasants had hardly any property at all, but if we estimate it (very generously) at one tenth of a pound of gold, the wealth differential would be 200,000! Inequality grew both as a result of the rich getting richer (late imperial senators were 100 times wealthier than their Republican predecessors) and those of the middling wealth becoming poor.”

Compare this to the America of World War II and the America of today. Wealthy, politically influential families such as the Kennedys could only retain their influence if their sons served in positions of combat leadership, and Joe Kennedy was killed in the European theater after volunteering for a highly risky air mission. John F. Kennedy very nearly lost his life in the South Pacific.

And how do our era’s crop of presidents and presidential contenders fare by comparison? The idea that flesh and blood should ever be at risk in defense of the nation /empire–perish the thought.

As Turchin sagely observed, it’s not just the limitless greed and avoidance of sacrifice of the elite that generates destabilizing inequality–it’s the eradication of the middle class as all the risks and sacrifices were shifted from the self-serving top to the middle and lower classes.

As I’ve often noted, risk cannot be made to disappear, it can only be transferred to others. In the grand scheme of things, the inherent risks of globalization and financialization have all been transferred to the middle and working classes (however you define them). The elite class enjoys the near-infinite support of the Federal Reserve and it’s ability to print near-infinite sums of currency to bail out the greediest, most self-serving scum of parasites and speculators.

Meanwhile, all the sacrifices required to support this unfair, corrupt, predatory system have been transferred to the middle and working classes via sleight of hand. The sacrifices weren’t transparent and up front; they were cloaked in the decline of job security, in ever-higher costs, in the decline of social mobility and the erosion of the purchasing power of wages.

The elites’ economist flunkies and factotums claimed that bailing out the freeloaders, parasites and speculators would benefit “the little people” because the grand trade-off delivered by the Federal Reserve (as correspondent R.J. pointed out to me) was: no more financial panics, which caused much misery in the working class due to business failures causing layoffs and unemployment.

But globalization, financialization and the rise of cartel-state monopolies have eviscerated the middle and working classes far more effectively and permanently than any brief financial panic, while greatly enriching the elite class–a rise in wealth that is backstopped by the Federal Reserve: profits are the elites to keep while their losses are socialized, i.e. transferred to the lower classes.

Job security, the purchasing power of wages and social mobility–nothing vital to the middle or working classes is backstopped by the Fed; the Fed’s one and only job is backstopping the wealth of our parasitic, predatory elite.

Sacrifice for Thee But None For Me. The banquet of consequences for the Fed, the elites and their armies of parasitic flunkies and factotums is being laid out, and there won’t be much choice in the seating.