By Jerome Roos

Source: RoarMag.org

Capitalism is a strange beast. Though incredibly resilient in the face of systemic crises and remarkably adaptive to ever-changing conditions, it never truly overcomes its structural contradictions. As the Marxist geographer David Harvey often points out, it merely displaces them in space and time.

The global financial crisis of 2008-’09 has been no exception in this regard. In fact, the very response to that calamity has already laid the foundations for the next big crisis. And just like its immediate predecessor, it looks like this one will be centered, at least in part, on a massive speculative housing bubble.

Officials and investors may still be turning a blind eye, but the warning signs are flashing red everywhere. From Shanghai to San Francisco, from London to L.A., a wave of real-estate speculation is washing over the world, gentrifying popular neighborhoods, pushing housing prices and rents to historically unprecedented highs, and forcing low-income tenants out of their increasingly unaffordable homes. The result is widespread social displacement and deepening discontent.

Unlike the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007-’08, which was centered on the complex packaging of risky loans to low-income households across the U.S., the new housing crisis is a product of real-estate speculation in the world’s major metropolitan areas. Take London, which according to the Financial Times finds itself confronted with “its biggest housing challenge since the Victorian era.” Residential property prices in the British capital have risen 44 percent since 2008, and are now well above their pre-crisis highs.

According to an analysis by the UK charity Shelter, there are currently only 43 homes in Greater London that could still be considered affordable to the average first-time buyer, pushing everyone but the richest of the rich into the rental market, where landlords are known to exact more than a pound of flesh in return for a roof and running water. In the majority of London boroughs, the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment is now over £1,000 per month. On average, Londoners spend about 60 percent of their income on rent.

A similar picture has emerged in New York, where property prices — in the words of the BBC — “have gone turbo-ballistic, as global capital in search of a safe haven has rocketed in.” The average monthly rent in Manhattan now exceeds $3,800, even as half of New York’s urban population lives near or below the poverty line. As a gubernatorial candidate for New York once aptly pointed out, “the rent is too damn high.”

Again, the unsurprising result has been widespread social displacement. Al Jazeera recently reported that “evictions [in New York] have reached epidemic proportions and created a new homeless crisis born out of an affordable housing shortage.” Other major cities like Boston and Los Angeles are not doing much better, as gentrification proceeds apace from coast to coast. Today, even the downtown area of derelict Detroit is rapidly gentrifying, while much of the city still languishes in a state of post-industrial decline.

It is San Francisco, however, that has emerged in recent years as the most paradigmatic case of unbridled gentrification. With median monthly rent hitting $3,530, the city has become the most expensive in the U.S. Desperate to get rid of old tenants who still enjoy rent controls and attract high-income professionals from the tech industry in their place, landlords have gone on an eviction spree: in the past five years, the eviction rate has soared more than 50 percent. Immigrant and working class neighborhoods like the Mission have been reduced to multi-million dollar playgrounds for the “bohemian bourgeois”, complete with snazzy coffee places and expensive vegan restaurants.

The urban sociologist Saskia Sassen has encapsulated the nature of this violent process in strikingly succinct terms: the social reality of financialized capitalism, she argues in her book Expulsions, is all about “systemic complexity producing simple brutality.” And as usual, those feeling the brunt of this brutality are the urban poor and marginalized communities, especially immigrants and people of color, who — along with artists and precarious youths — are increasingly being displaced from city centers towards the periphery.

It is not just cities in the advanced capitalist countries that have been undergoing this turbulent process of urban stratification: the major metropolitan areas of the Global South are firing on all cylinders as well — with the notable difference being that the bubble in emerging markets already appears to be in the process of popping, raising fears of a new international financial crisis centered on China, Brazil and Turkey, among others.

In China’s biggest cities, property prices shot up 60 percent between 2008 and 2014, with residential prices in Shanghai and Beijing rapidly closing in on those of London, Paris and New York. According the consultancy firm McKinsey, some$9 trillion — almost half of China’s total debt, excluding financial sector debt — “is directly or indirectly tied to real estate.” Price increases have exceeded the rise in income by 30 percent in Shanghai and by 80 percent in Beijing.

Other major cities that have been experiencing similar real-estate booms include São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, where residential property prices in the most-desired neighborhoods doubled between 2008 and 2013, and Istanbul, along with the other big cities of Turkey, where a credit-fueled construction boom has accounted for 30 percent of GDP in the period since Erdogan’s AKP came to power on the heels of a previous financial crisis in 2002. Since 2007, property prices in Turkey have shot up 36 percent.

To be sure, the local specificities vary from place to place. In London, the housing crisis has been fueled at least in part by massive capital inflows from wealthy elites in countries like China, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, as well as the municipality’s failure to build adequate housing for the large influx of new inhabitants. In Barcelona, by contrast, it has been driven primarily by the tourism industry, while in San Francisco it is largely driven by the tech industry. In Rio, the process has been intensified by preparations for the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games, while widespread cronyism and corruption have been an important catalyst for the construction boom in Istanbul.

Yet for all differences between them, the gentrification processes and housing crises in each of these global cities share two crucial commonalities: first in their causes, and second in their consequences.

In terms of the underlying causes, the new housing crisis should be seen as a direct outcome of the response to the previous crisis, which was based on massive bank bailouts and central banks opening the floodgates of cheap credit. With the notable exception of the ECB, which only embarked on quantitative easing earlier this year, the world’s largest central banks dropped interest rates to historic lows, kept them there for years on end, and pumped trillions of dollars of fresh liquidity into the global financial system, effectively subsidizing private investors out of bankruptcy.

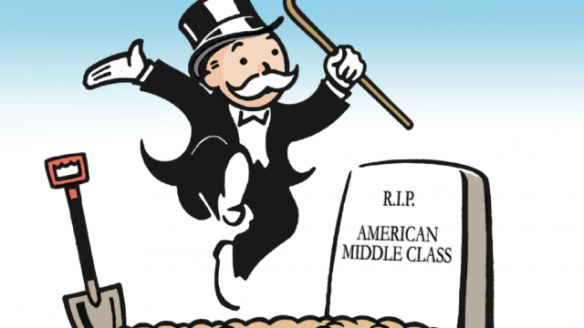

This unlimited flow of free money (for the 1% only, of course) produced a tide of surplus capital that had to be absorbed somewhere. With “secular stagnation” taking hold across the developed world, investors were still wary to direct this surplus towards the productive economy, where profit margins remained relatively low. And so, in their insatiable quest for yield, they turned to speculative investment in various asset classes instead: stocks, bonds — and, once again, real-estate. The profits were phenomenal. By 2012-’13, the resulting speculative boom had led U.S. corporate profits back to a new all-time high.

But now that the first signs of overheating have become apparent, we can already begin to identify the second crucial commonality between today’s urban housing crises; a commonality that sets the current crisis apart from the last one: in almost all of the major world cities today, ordinary citizens are already actively mobilizing and fighting back against processes of gentrification, dispossession and displacement, building innovative social movements and powerful political platforms in the process.

From urban insurrections to defend the last-remaining green space of Istanbul or the favelas and public transport system of Rio, to the local direct action of anti-gentrification activists targeting Google buses in the San Francisco Bay Area and reclaiming housing projects in London, it is already clear that the next major crisis, unlike the last one, will not go uncontested.

Of all the urban struggles that have ignited across the globe in recent years, the radically democratic municipal platforms of Spain are undoubtedly among the most advanced and the most promising. With the left-wing anti-eviction activist Ada Colau now holding the mayoralty of Barcelona, an important sign is being sent to the landlords, gentrifiers and real-estate speculators of the world: even in the deepest crises, there will be a limit to your capacity to evict us from our homes and destroy our cities — and that limit, ultimately, is us.

Jerome Roos is a PhD researcher in International Political Economy at the European University Institute, and founding editor of ROAR Magazine. Follow him on Twitter at @JeromeRoos.