A thought-provoking sci-fi thriller set in the future that taps into some of the most troubling inequities and problems of our era, the lack of time.

By Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

Source: Spirituality and Practice

The best science fiction always uses some trend or policy of the present as a foundation and projects it into the future with a picture of some possible results. Through this glimpse of tomorrow, we can ponder anew the spiritual or philosophical ramifications of what we are doing today. In The Adjustment Bureau, we were given a chance to assess the idea of free will or the alternative of following a plan mapped out by God. In Gattaca the idea of genetically engineered perfection is explored. Writer and director Andrew Niccol who wrote and directed the latter thriller is also at the helm of this thought-provoking sci-fi drama that has many resonances with today’s world.

The Preeminence of Time

A search on Google for “time” yields more than 11 billion hits whereas there are fewer than 3 billion hits for “money” and 241 million hits for “sex.” Time is very much on our minds and at the hub of our concerns. We speak of “having” and “saving” and “wasting” time but we never seem to find a way of “conquering” it. We are caught up in the obsessive-compulsive need to make the most of the time we have each day. Pagers and cell phones are taken everywhere. We don’t want to miss a moment of connection.

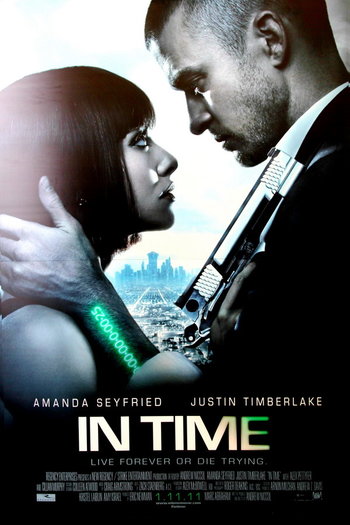

In Time is set in a future dystopia where living zones separate the rich from the poor. Will Salas (Justin Timberlake) lives in a ghetto zone with his mother Rachel (Olivia Wilde). She looks very young since all aging stops at 25.

Will works in a factory and she has a job as well, but still it is hard to make ends meet. Time in this society is literally money. Each person has a timer on his or her arm and at 25 you are given one year of free time after which you die — unless you can find a way to get more time. Wages are doled out in days of added longevity. All expenses (rent, a cup of coffee, clothes, phone calls) are paid for with time and scanners are used to deduct the time for the purchase. The biggest fear in the ghetto is that your time will run out unexpectedly. That is exactly what happens to Will’s mother.

Time Is Strange

“Time is stranger and deeper than anything else in our lives.”

— Jacob Needleman

The biggest dream in the ghetto is acquiring a surplus of years and the prospect of immortality. When Will saves a young man with a century on his clock, the fellow gives the years to him and then commits suicide. An intrepid “Timekeeper,” Raymond Leon (Cillian Murphy), is convinced that Will stole the years from the dead man. He launches a man hunt for him. Also hot on Will’s trail are some nasty time thieves.

Caught in Time

“Time is the element in which we exist. We are either borne along with it or drowned in it.”

— Joyce Carol Oates

Will begins a daring journey into the zone for the time rich called New Greenwich. After winning more than a millennium at a casino, he meets Sylvia (Amanda Seyfried), the daughter of Philippe Weis (Vincent Kartheiser), an immensely wealthy and powerful banker who has been exploiting the poor by making high interest time loans. A believer in “Darwinian capitalism,” he’s stored up enough years to be immortal. But Sylvia thinks there must be more to life than the favored existence she knows. She is intrigued by Will’s wild ideas about changing the system which favors the rich over the poor and allows many to die so a few can be immortal. After he takes her hostage when the Timekeeper is closing in on him, Sylvia doesn’t take very long to pledge her allegiance to what becomes their own mutual crusade. They begin robbing time banks and giving time to the poor and the down-and-out.

In Time is a winning sci-fi thriller that taps into some of the troubling problems of our era, such as the view of time as money, the growing gap between the rich and the poor, and all the ways that we waste time and fail to value every moment. It is also a meditation on the healing and restorative medicine of generosity and sharing. Writer and director Niccol has given us a cautionary tale about the possible future consequences of class consciousness, the high cost of trying to stay young or live forever, and the need for something more meaningful than just spending time to get ahead of the game.