By Caleb Quass

Source: Medium

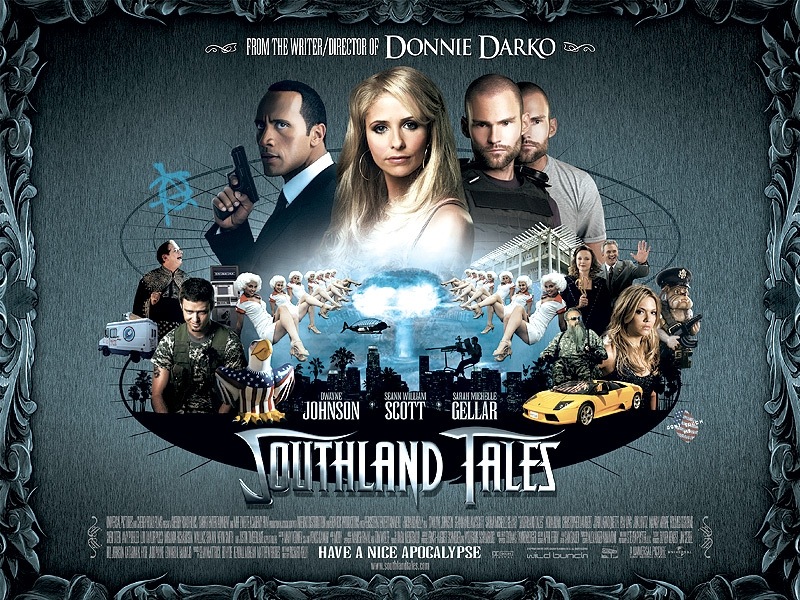

Enigma as a thematic device in itself is something I’ve applied to the films of David Lynch and his surrealist ilk, but until my third viewing of Donnie Darko, it’s not something I had considered for Richard Kelly’s debut film. Viewing once again the theatrical cut of the film, I started wondering whether or not the significantly-extended director’s cut could actually offer anything significant in its additional footage, or if it would merely obfuscate such an atmospherically uneasy movie through its clarity.

Like the characters’ immature dialogue and the mostly non-nostalgic depiction of a recently bygone era, the mysterious and almost unknowable nature (at least from casual viewings) of Donnie Darko’s happenings come across as a manifestation of the turbulence and teenage angst that define the titular character (Jake Gyllenhaal). That the film features such subtly brilliant performances and an alluringly spooky atmosphere are just the icing on the cake but just as important in rendering this a truly brilliant film.

Plot summaries have always been weirdly difficult for me, and that’s especially the case with the disorienting stream of events that Donnie Darko offers. The psychologically-unstable social outcast is awakened by a giant bunny rabbit and lead from his bedroom, where shortly after a jet engine mysteriously crashes through the roof in what would have almost certainly been his demise. This “imaginary friend” Frank continually appears and speaks to Donnie, compelling him to commit destructive acts with far-reaching consequences.

All the while, he regularly sees his therapist, forms a relationship with a new student (Jena Malone), experiences “daylight” hallucinations related to time travel, researches time travel via a book written by the town’s unspeaking hermit “Grandma Death” (Patience Cleveland), and generally copes with the frustrations of being a precocious, cynical teenager in a conformist society — all as Frank forebodingly counts down the “28 days, 6 hours, 42 minutes, 12 seconds” until the world ends.

There’s a lot going on, but even as Donnie Darko climaxes without the sort of resolution that audiences may expect, it’s never unwatchable or less than compelling. From the opening minutes of the film where Donnie rides his bike around a darkly-photographed suburbia to the post-punk stylings of Echo and the Bunnymen, a mood is established and never broken. It’s typical Midwest American iconography through the lens of a disillusioned adolescent, and though the slow-motion, pop music-infused high school sequences, as well as the dialogue of aimless friendships and budding romances, are reminiscent of coming-of-age dramadies, Donnie Darko never embraces these things as genuine or even necessarily normal. Scenes have a tendency to bleed into one another with the slightly-hurried pace of the “paranoid schizophrenia” which Donnie’s therapist (Katherine Ross) offers as an explanation for the hallucinations, and the already somewhat downbeat pop music is complimented by a jittery, melancholy score by Michael Andrews.

Perhaps most peculiar of all, though, is the look of the film in general. The interiors of Donnie Darko are just a little too dark, and its daylight scenes just don’t feel sunny, as though constantly threatened by an impending storm. Something is extra dismal and extra drab about every classroom, street, and upper-middle-class household, and though this is an extraordinarily subjective designation, it just looks depressed. Donnie never forms an especially healthy relationship with anyone in the film, and his extrasensory premonitions are apt counterparts to his frustrations with society, labeling as an outsider, and all the implicit complexities of puberty.

Though admirable for its thematic strengths, Donnie Darko ultimately makes its impact through its sneaky emotional core, which continually grows in the background until exploding in the film’s fatalistic conclusion. Here again the movie embraces a pubescent concept, the notion that one’s own life is a direct burden on others, but with a sobering shift in perspective. After his mind-bending odyssey results in the literal death and figurative destruction of multiple people, Donnie’s ultimate fate is to sacrifice himself to undo his supposed harm upon the world, harm which, paradoxically, only occurred through his quest to stop it. On the level of pure logic, this might not make sense, but on a dramatic level, it’s pure poetic tragedy. The film’s “Mad World” montage could have been a miserable failure in its sudden spike in melodrama, but instead it is the culmination of the sorrow and emotional terror that was just beneath the surface all along.

The entirety of human emotion cannot, as the delusional teacher played by Beth Grant suggests, be divided into “fear and love” or any other two extremes. Donnie understood that, but what neither he nor anyone else understands is exactly how it does function. Donnie Darko is a masterpiece not because its convoluted story offers any answers, but because unlike the majority of shallow coming-of-age narratives, it knows that it can’t.