Ace in the Hole

By Brian Eggert

Source: Deep Focus Review

An embroidered sign on the wall of the Albuquerque Sun-Bulletin reads, “Tell the Truth.” The paper’s managing editor, the moral and idealistic journalist Jacob Boot, hung it there “as a sign of his and the newspaper’s guiding ethic.” But ethics are something reporter Chuck Tatum has done without, which, along with his drinking (“Not a lot, just frequently”), earned him the sack from several daily papers on the east coast. Now relegated to hungrily petitioning for a job at a small New Mexico paper, Tatum tells Boot, “I can handle big news and little news. And if there’s no news, I go out and bite a dog to create some.” To be sure, the Sun-Bulletin’s guiding ethic is something of a joke to Tatum, and to filmmaker Billy Wilder, who layered Ace in the Hole with caustic pessimism toward the insincerity of American culture and the media’s failed capacity for truth. It would be one of Wilder’s most personal films, having written, produced, and directed the film with less studio meddling than he had ever experienced. But in 1951, Wilder’s picture debuted and vanished without a trace in one swift motion, disregarded by critics and audiences as the director’s most sneering demonstration of his worldly cynicism. Today, Ace in the Hole represents an artistic zenith in Wilder’s career, where his skill as a filmmaker and thorough condemnation of the human race converge into biting social commentary that stands apart from his more commonly known hits.

Along with many other directors of his day, Wilder (Jewish, and of Austrian-Hungarian descent) fled Adolf Hitler’s looming rein over Europe in the late 1930s. Wilder left Paris for the United States and, given his experience in the European motion picture industry, landed work as a Hollywood screenwriter. For the better part of his early career, he collaborated with his writing partner Charles Brackett on a number of popular films. Their early hits include Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939) and the Howard Hawks screwball comedy Ball of Fire (1941). He soon petitioned Paramount Pictures to allow him to write and direct his own film exclusively and, based on the impressive successes of Hollywood’s first comedic writer-director Preston Sturges (The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels), Wilder was given his chance. While German filmmakers were best known for their blatant expressionism, Wilder surprised Paramount studio heads in 1942 when his blithe and commercial debut The Major and the Minor turned out to be a box-office triumph. It was completely devoid of any unmarketable German-ness so well known in Hollywood from directors like Fritz Lang, as Wilder intentionally set out to make a commercial crowd-pleaser—if only to prove to studio heads that his films could earn a profit and connect with audiences so that later he could branch out.

Established as a bankable success, Wilder would go on to helm several benchmark pictures, many of them blending unconventional material with commercial appeal. Double Indemnity (1944), about a femme fatale who convinces her insurance agent to kill her husband, became an archetypal noir story; The Long Weekend (1945) was about an alcoholic on a serious bender and won the Oscar for Best Picture and Wilder a statue for Best Director; and Sunset Boulevard (1950) reflected Hollywood in a morbid, dark light, but also earned several Oscars and an immovable place in film history. In fact, many of Wilder’s films earned such a place. Though, Wilder remained best known for later comedies and romances like Sabrina (1954), The Seven Year Itch (1955), Love in the Afternoon (1957), Some Like it Hot (1959), The Apartment (1960), and Irma La Douce (1963). Each winks to the audience by testing the boundaries of orthodoxy. A Foreign Affair (1948), for example, is somehow a romantic comedy, despite its setting in the otherwise humorless postwar Berlin. His movies were best known for their irony and unconventional settings, for their light lampooning and harsh criticism of established norms. Wilder was an incredible dramatist, a superb romantic, but foremost a satirist. Among them all, Ace in the Hole’s rebellious and unrelenting pessimism prove alarming when compared to the filmmaker’s more popularized string of successes.

Development on Ace in the Hole began just after Wilder finished work on Sunset Boulevard and separated from his longtime writing partner Charles Brackett. In his search for a replacement writing partner, he found Walter Newman, a 23-year-old writer of radio plays. Newman suggested they adapt a real-life event: On January 30, 1925, cave explorer W. Floyd Collins was trapped in Sand Cave in Kentucky when a landslide pinned him down. Learning of this, William Burke Miller, a reporter for the Louisville Courier-Journal, crawled through a narrow opening to interview Collins. Miller’s story made national headlines. Local crowds and tourists gathered to watch the rescue efforts; businesses came to provide the crowds with distractions during their considerable downtime. Vendors sold hot dogs and a record huckster even wrote a song for country singer Vernon Dalhart. It later sold 3 million copies. Before long, the sheer number of people and vendors equated to a county fair or carnival, all of them forgetting that there was a man trapped and dying nearby. Collins was trapped for eighteen days before he died. Miller won a Pulitzer Prize in 1926 for his reporting. For Wilder, the story was not surprising. He worked for a scandal sheet in the 1920s while in Berlin. “I was doing the dirty work of crime reporting… Some of this I remembered for Ace in the Hole.” In one of Wilder’s anecdotes about his time as a reporter, he recalled being assigned to interview the parents of a murder victim and parents of a murderer. He admitted to making up the answers to the questions for the murderer’s parents; he couldn’t bring himself to face them. Wilder knew other journalists went to similarly subjective lengths.

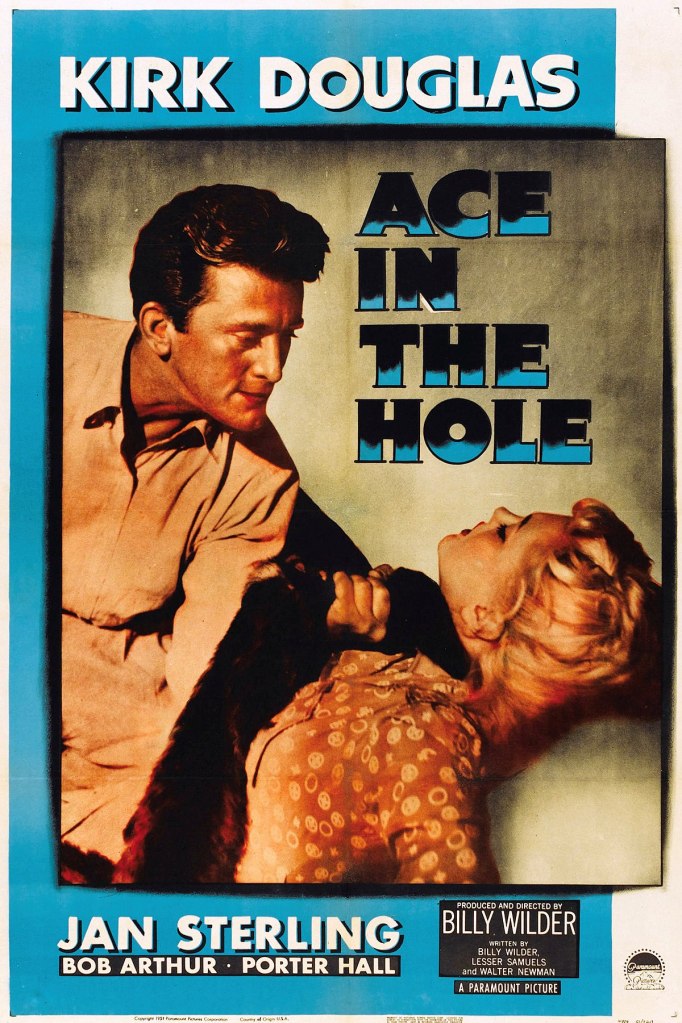

A scarring indictment of journalism and, by extension, American culture, was just the sort of project he wanted to make as his first effort away from Brackett. Along with Newman, Wilder also invited the contracted Paramount writer Lesser Samuels, a former newspaper man, to join in telling a story that bore similarities to Collins’ fate. Their then-titled treatment “The Human Interest Story” was greenlit by Paramount with a budget of $1.5 million, $250,000 of which went to Wilder. Nonetheless, many in Hollywood doubted the project and held misgivings about what Wilder would produce without Brackett. Many felt that Brackett helped rationalize and tone down Wilder’s otherwise virulent cynicism. Aware of how he was seen throughout the industry, Wilder nonetheless continued to explore the most cynical film of his career. To protect himself and his next film, Wilder kept its subject matter under tight wraps. He handwrote a note on the first draft saying, “Do not give out under any circumstances—to anyone!” Had even the basic story leaked, not only would his detractors have ammunition with which to accuse him of rampant cynicism, but the press would certainly not be in favor of a film that sets out to lambaste the media. Meanwhile, Wilder signed Kirk Douglas to play the film’s resident William Burke Miller, here named Chuck Tatum—a deceitful reporter who creates the news with his own braggadocio and slick maneuvering. To prepare for Douglas for the role, Wilder sent him to work at the Herald Examiner as a novice reporter for a week.

Principal photography began on July 10, 1950, and wrapped on September 11, with the screenplay having been completed just four days earlier. Censor Joseph Breen had a few complaints about the lack of “a proper voice for morality,” citing the generally disparaging tone of the piece; however, because the protagonist’s utter lack of scruples result in him paying for his nihilism with his life, Breen had few demands for changes. Breen insisted on a single change in which the corrupt sheriff, Gus Kretzer (Ray Teal), whose role in the film’s central scandal goes unpunished, receives some manner of comeuppance. Wilder conceded and, in the end, he resolved to add a line about the newspaper’s editor Jacob Boot (Porter Hall) writing an exposé on the sheriff’s wrongdoings. For the visual presentation, Wilder and cinematographer Charles Lang wanted an authentic look far removed from many of then-current directors of photography. Wilder admired cinematographers who weren’t “working for the goddamned Academy Award”—who didn’t use “fancy camerawork, with the camera hanging off the chandelier.” Lang’s work is gritty and real, with brief touches of high-contrast shadows and noirish influence. Critic Manny Farber described Lang’s work on Ace in the Hole as having “a chilling documentary exactness.” On the periphery, Victor Desney, an actor who had approached Wilder about adapting Collins’ story two years earlier, learned about the production at Paramount and filed a lawsuit. Though Wilder and his writers changed the names and locations for the script and initially won their case, an appeal filed in the California Supreme Court ruled in favor of Desney. Wilder and his lawyers settled privately for a hearty sum.

Journalist William Burke Miller’s moral bankruptcy was surely exaggerated by the film, as Tatum’s Machiavellian cunning and self-centered portrayal is given intense bravado by Douglas. Tatum is a charismatic, ambitious, megalomaniac personality, yet filled with self-contempt. The story begins with Tatum, a hard-luck newspaper writer who talks loud, thinks fast, and belongs somewhere in a city scouring slums and politicians’ bedrooms for a story. Nevertheless, no city will have him. He’s been fired from eleven newspapers around the country for reasons ranging from drinking on the job to sleeping with the editor’s wife. His former salaries were more than anyone in the “sun-baked Siberia” of Albuquerque, where he finds himself when the film begins, has ever come close to earning. Casing the offices of the local paper, Tatum speaks with as much modesty as you will see from him—he tells the owner that taking him on will make the paper $200 a week, as he is a $250 writer willing to take the job for $50. Once hired, even a year later, Tatum still lights matches off typewriter recoils, scoffs at the paper’s embroidered “Tell the Truth” motto, and talks of his New York City glory days as if there were still a chance for him. All the while, he waits for a Big Fish to come along, onto which he hopes to snag his hook and pull himself out of his dinky Albuquerque boat, into the river and down all the way to New York City once again.

Beginning to feel that biding his time in New Mexico’s empty pasture of newspaper journalism might be his last mistake, Tatum sees a way back into The Big Time when driving to a rattlesnake festival (“Even for Albuquerque this is pretty Albuquerque,” Tatum remarks). By chance, Tatum and his gopher photographer stop at a wayside trading post and restaurant; they learn the store’s owner is trapped inside a centuries-old Native American cave system while digging for artifacts to sell. Remembering a journalist who years ago won a Pulitzer for dragging out such a story to its full dramatic scope (likely an in-film reference to Miller), Tatum sees the predicament of Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), the pleasant store owner and war vet who remains trapped in a tiny opening, as the perfect opportunity. Tatum explains, “Bad news sells best. ‘Cause good news is no news.” As with other Wilder protagonists, Tatum takes the low road to raise himself up, selling himself for the concept of personal accomplishment, not yet realizing the consequences until he ends up dead—a reoccurring theme in Wilder’s films since Double Indemnity. Tatum takes control of the rescue operation, out-talking even the local police; he bribes Sheriff Kretzer with the idea of reelection and fame from newspaper coverage. A contractor familiar with cave rescues wants to fasten the unstable walls with bearings, which should allow Minosa’s rescue in half a day. Too dangerous, Tatum explains. He suggests using a drill and going in through the top of the mountain—a decision that will extend Tatum’s newspaper treatment by days, allowing him to gain the attention of New York City’s high-brow journalists.

Tatum’s coverage attracts local attention. Tourists stop by just to get a look at the cave where “hero” Leo Minosa remains trapped. And then there’s Minosa’s wife, Lorraine, played by the appropriately desperate and tired-looking Jan Sterling. She seems none-too-broken up about her husband’s predicament—she uses Leo’s absence to try and leave him, until Tatum convinces her to stay for the event’s profits. After all, the crowds at the spectacle buy burgers at the Minosa trading post, giving Lorraine more business than they’ve had in, well, ever. (“We sell a case of soda pop a week, and once in a while a Navajo rug,” she admits.) Eventually, Lorraine comes on to Tatum, hoping that he can whisk her away from her isolation, off to The Big City. Through a few subtle glances, we realize Lorraine knows just what Tatum is up to. “That’s the first grand I’ve ever had,” she says to him after a good day of business, smiling with sexual conviction. “Thanks. Thanks a lot.” Tatum instructs her to get that smile off her face, that she has the part of a distraught wife to play. “Why don’t you make me?” she says. Tatum slaps her hard across each cheek and her smile is replaced with angry confusion. “Don’t wipe those tears,” he says. “That’s the way you’re supposed to look.” It is a vicious, scary moment in the film, one where we realize how cruel and manipulative Tatum truly is, and how breathtaking an actor Douglas could be.

Compare Douglas’ Tatum to his character Jim McLeod in William Wyler’s Detective Story, released the same year as Ace in the Hole. Both characters are driven, self-aware, and conscious of their own moral downfalls. McLeod resorts to criminality to put criminals away; Tatum creates his own stories for journalistic purposes. Douglas excels in these roles, both powerful, flawed men. Their brash sensibilities are subdued only by Douglas’ natural, charming confidence. And while each character may be anti-heroic, to the point where we know they must die in the end to amend their misdeeds, we root for them, as they are uniquely sympathetic and convincing in their passions. By the time the drill is set up on top of the mountain, Lorraine is selling tickets to her husband’s imprisonment in the cave, even letting the circus erect tents, sell concessions, and sing songs about rescuing Leo—giving a very literal meaning to “media circus”. Wilder commissioned Paramount’s songwriting team of Jay Livingson and Ray Evans to write “We’re Coming, Leo”, a song to commemorate the cave-in, instructing them to write “the worst song you can, with bad rhymes and everything else bad.” A woman in a cowgirl getup sells copies of the song to spectators. Parents buy Indian headdresses for their children. Servers carry orders of food through the crowd. The throng’s blithe and entertained. A billboard claims the “proceeds go to the Leo Minosa Rescue Fund,” but undoubtedly, no one but the vendors will see a dollar. Wilder’s critique of postwar America is unremitting.

Flourishing under such conditions, Tatum juggles prearranging a job contract with a New York newspaper, keeping quiet those who know his secrets, communicating with Leo and instilling in him hope, and maintaining order in the newly constructed “community” just outside the cave. Wilder captures the cynical nature of the truth and media by exploring the reporter, his victims, and those who allow his plan to progress. His ending leaves both Leo and Tatum dead. “I’m a thousand-dollar-a-day newspaperman,” Tatum tells his idealistic Albuquerque editor. “You can have me for nothing.” Tatum falls to the ground, lifeless from a stab wound incurred by the rejected Lorraine. The final shot is Wilder’s only bravado shot in the picture, with Douglas dropped to within an inch of the camera’s lens. After all his efforts, Tatum could not assure than Minosa would live the week needed to once again boost his name. And yet, in the end, Tatum is not just a remorseless journalist; he’s riddled with guilt, but not enough to end his coldhearted behavior. Leo dies needlessly in the cave off-screen, believing Tatum is his friend to the last moment. Lorraine is left pathetically clinging to her profits. When the circus finds out Leo is dead, collective heads drop in sadness; within moments the makeshift parking lot is abandoned and only scattered garbage remains. Tatum failed to secure a much needed happy ending to his human interest story; had Leo survived, perhaps Tatum would have lived in the end. But that would be another film entirely.

As with so much modern media, Tatum decides what his readers know and where the story goes. He reports on and develops his yarn in the manner to which he desires. Television and newspaper journalists choose what they report, and more often than not it’s the type of news their audience wants to hear. This is a subjective, sensationalist process, guided by money and ratings as opposed the ideal objectivity professional journalists have forever yearned for but rarely achieve. Tatum takes subjectivity to the next level: interaction. While Ace in the Hole may seem satirical with Tatum pulling the locals’ strings like a puppeteer, reconsider the film’s basis in fact, that such events actually occurred to an extent. In some instances, they still occur today. In 1998, Steven Glass was famously fired from The New Republic magazine for fabricating entire stories. Names, places, events—all made-up. This is, of course, the next extension beyond what Tatum does in the film. And luckily, no one died from Glass’ actions; moreover, since there is no law against bad journalism, Glass was never punished. Fortunately, cinema can provide a cathartic, poetic justice. Like any great film noir, the criminal hero, Tatum in this case, is punished in the end for his wrongdoings, a narrative archetype that Wilder all but established with Double Indemnity. Though Ace in the Hole is not, for the most part, shot in the visually expressionist noir style, its plot conforms to traditional noirish devices—complete with an equally corrupt blonde bombshell to parallel the anti-hero. Only in the final scene, as Tatum collapses to the ground do we see Wilder’s noir intent. Douglas’ visage is barely lit but for a highlighted cheekbone and lower eyelid, so near we cannot help but confront the reality of Tatum’s death.

Perhaps this film’s cynicism explains its abortive performance in America, where critics found Wilder’s pessimistic attitude toward the unlikely chances of credible journalism offensive, and audiences altogether ignored it. Furthermore, the film illustrates general human corruption, since most of the film’s characters, save for Leo and Booth, are bought by Tatum’s charm. Curious that Paramount allowed such a powerfully overcast film to be made, or even believed audiences in 1951 were willing to endure such material. Even today, Ace in the Hole shocks for its blatant display of corruption otherwise commonplace amorality. The comparatively raw audiences of 1951 were not used to seeing such barefaced gloom and hopelessness depicted onscreen, unless film noir was their genre. While earning accolades in Europe, the picture was all but forgotten shortly thereafter. Poor receipts in North America panicked Paramount executives, who changed the title to “The Big Parade” briefly—a change that did little to increase attention to this sour-flavored picture. In Europe, which at the time was blossoming with some of the best in filmic auteurism, and which had no qualms about a film scorning American journalism and culture, Ace in the Hole was widely regarded as a masterpiece. When asked if Ace in the Hole was a cynical film, I. A. L. Diamond, Wilder’s co-writer on Some Like it Hot, said, “Sure they called it cynical. And then you see thousands and thousands of people turning up at Idlewald airport in New York to watch a plane coming down with bad landing gear. People clog the runway waiting for it to crash—and you ask yourself how cynical Ace in the Hole really was.”

In the wake of the film’s failure, Wilder’s break with Brackett was also blamed. Wilder resolved never to work with either Newman or Samuels again, not that the studio would back another collaboration between them after Ace in the Hole‘s failure. And because Paramount’s next Wilder movie, Stalag 17 (1953), was a huge success both commercially and artistically, Wilder’s salary for that film was purportedly withheld by Paramount to make up for the studio’s massive losses. “Fuck them all,” Wilder said of Ace of the Hole‘s critics. “It is the best picture I ever made!” Not long after the film’s release and its scathing reviews, Wilder witnessed a car accident in which a man was run over right in front of him. As Wilder got out of his car to check on the victim, a newspaper cameraman took a picture of the scene. Wilder told the cameraman to call an ambulance, but he replied, “I’ve got to get to the Los Angeles Times. I’ve got a picture that I’ve got to deliver.” Wilder said, “You put that in a movie, the critics think you’re exaggerating.” While Ace in the Hole was described as being from the “rattlesnake’s view of the world” by critics, today the ethical injustices committed by contemporary journalists far exceed those of Chuck Tatum. Years later, the film was almost universally forgotten, seen only occasionally on television. In 2002, the AFI declared it an overlooked masterpiece and held a special screening hosted by Neil LaBute. Five years later, New York’s Film Forum showcased the film with a newly restored print. Film historians around the world have since praised it with a newfound adoration and appreciation for the director’s purest voice.

Sayings like “ahead of its time” or “forward-thinking” do Ace in the Hole little justice. The film captured the lowest depths of 1950s journalistic misconduct, but also reflected the wasteland that Wilder believed American culture to be with supreme viciousness. Sensationalism and subjective reporting—amid contemporary saturation via social media, television, radio, newspapers, magazines, and even cinema—have become more commonplace and monstrously unrestrained today than perhaps even Wilder could have imagined them becoming. Then again, the mutation of the media and our ever-increasing obsession with spectatorship would have disgusted Wilder, but they wouldn’t have surprised him. Lost to time and further eclipsed by the director’s landmark productivity after its release, Ace in the Hole’s cutting-edge criticism of journalistic integrity, or lack thereof, presents one of the most scathing samples from Wilder’s career of hard-biting satires and comic romances. Wilder saw Tatum’s unfeeling opportunism as a small sampling of what’s wrong with our culture. His censure of the media extends further to a vicious condemnation of American culture, specifically those who remain drawn to sensationalism regardless of who is harmed for their entertainment.

Bibliography:

Hopp, Glen. Billy Wilder: The Complete Films, The Cinema of Wit. Taschen, 2003.

Horton, Robert (editor). Billy Wilder: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001.

McNally, Karen (editor). Billy Wilder, Movie-Maker: Critical Essays on the Films. McFarland, 2010.

Phillips, Gene D. Some Like It Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

Sikov, Ed. On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder. New York: Hyperion, 1998.

Watch Ace in the Hole on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/kcls/video/3520733