Movie review: Annihilation

By Frank Kaminski

Source: Resilience.org

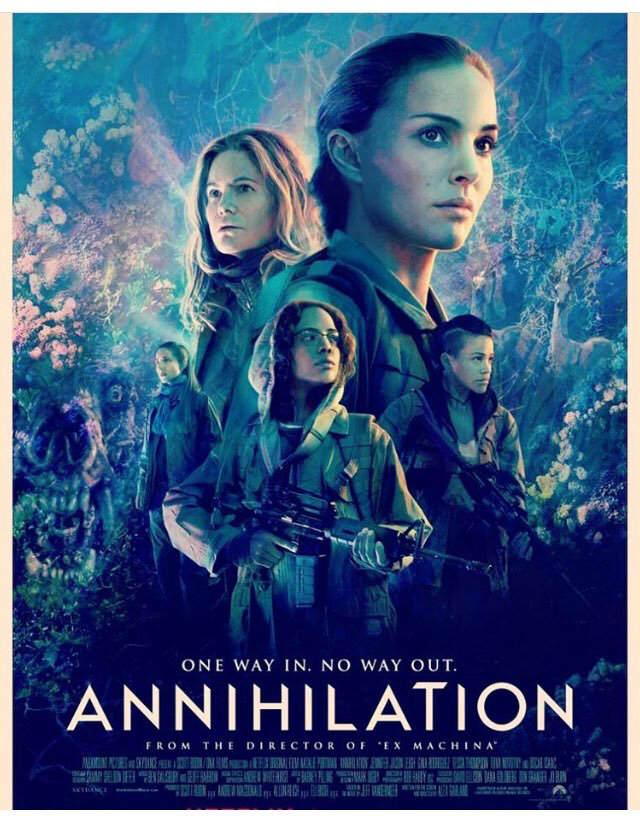

Annihilation

Directed by Alex Garland; screenplay by Alex Garland; based on the novel Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer; cinematographed by Rob Hardy; edited by Barney Pilling; music by Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury; production design by Mark Digby; produced by Eli Bush, Andrew Macdonald, Allon Reich and Scott Rudin. Released in Feb. 2018 by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 115 minutes. Rated NNN

Starring: Natalie Portman as Lena, Oscar Isaac as Kane, Jennifer Jason Leigh as Dr. Ventress, Gina Rodriguez as Anya Thorensen, Tuva Novotny as Cass Sheppard, Tessa Thompson as Josie Radek, David Gyasi as Daniel and Benedict Wong as Lomax

There are many layers to this smart, tense, slow-building science fiction drama. It’s at once a nuanced exploration of trauma and identity, a surreal excursion into high-concept cosmic horror and an endlessly rich subject for intellectual debate. It’s a movie that invites many interpretations, having been read as a metaphor for everything from depression to cancer to radioactive contamination following a nuclear accident. Perhaps its most poignant subtext is that of nature fighting back against the encroachments of human civilization.

Loosely based on an eponymous 2014 novel by Jeff VanderMeer, Annihilation centers around a journey to the heart of an anomalous region known as Area X on America’s southern coast. Three years earlier, a meteorite crashed into a lighthouse in a national park, bringing with it an extraterrestrial entity that has since been transforming everything around it. During its spread inland, the alien has forged new ecosystems filled with mutations like something out of a psychedelic vision. At the edge of the contaminated zone lies a hypnotic, pulsating electromagnetic field called The Shimmer, from which almost no one who enters ever emerges—the one man to have done so bearing little trace of his former personality or memories afterward.

A clandestine government organization called Southern Reach has been created to study Area X with the aim of halting and reversing its progress. But Area X is impervious to satellite surveillance, and no one has picked up radio transmissions from any of the numerous teams that have ventured inside. So far, Southern Reach has managed to keep Area X under wraps, using the pretext of a chemical spill to evacuate the sparsely populated swampland that has thus far been consumed. But it’s only a matter of months before Area X will begin to expand into population centers, raising the prospect of mass evacuations that will be much harder to explain.

In the movie’s opening scene, the sole survivor of the latest expedition into Area X, a cellular biologist named Lena (Natalie Portman), is being questioned in a small, bare room by Southern Reach agents in hazmat suits. It’s been four months since she and the rest of her team embarked on their mission to reach and study the lighthouse that appears to be The Shimmer’s epicenter. The other members of her group were psychologist Dr. Ventress (Jennifer Jason Leigh), paramedic Anya Thorensen (Gina Rodriguez), geomorphologist Cass Sheppard (Tuva Novotny) and physicist Josie Radek (Tessa Thompson). They left with food rations, camping gear, weapons and their various scientific instruments. Lena’s questioners want to know what became of the others, how Lena lasted for months on only two weeks’ worth of food and what transpired between her and the lighthouse entity. The movie then flashes backward to recount the saga.

Portman gives a strong, sympathetic performance. Her character’s personal journey—which involves coming to terms with the fate of her husband Kane (Oscar Isaac), a special forces officer who was part of an earlier mission—forms the emotional core of the story. Leigh, who plays the group’s stoic leader, seems strangely subdued at first, until we come to understand her character’s motivations for heading into Area X. All of the actresses excel as action heroines during the movie’s periodic swings into action-thriller mode.

Unfortunately, some of the characters are given more to do than others. Lena and Josie are the only ones who really put their respective areas of expertise to use, each making important discoveries that advance our understanding of the entity’s threat. The others might as well just be soldiers.

Though subtle at first, the aberrations to the landscape and its flora and fauna grow increasingly dreamlike the closer the group comes to the lighthouse. The early mutations are, to use Lena’s words, “Corruptions of form. Duplicates of form.” But eventually the women encounter humanoid shrubs, stems harboring multiple plant species, an alligator with shark-like concentric rows of teeth, deer with flowering branches for antlers and trees made of glass. Josie hypothesizes that the alien being is a prism that refracts not only light rays and energy waves, but molecular structures as well, including DNA. This explains how shark’s teeth ended up in the mouth of an alligator, how sand formed into glass trees and how plants have melded with one another and with humans and deer.

Freakish things soon begin happening to the bodies and minds of our protagonists. Examining a drop of her own blood under a microscope, Lena finds it suffused with rapidly dividing alien cells. Anya is unnerved to see her fingerprint patterns moving. Paranoia begins to overrun the group. Some of the women fall victim to the creatures of Area X, while others turn into them, like Gregor Samsa becoming a cockroach in Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis.” Characterized by intense emotions and moments that seem to occur out of sequence and without logical explanation, these events play out much like a dream sequence. This feeling is heightened by Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury’s musical score, whose sounds become increasingly unnatural and mesmerizing.

The movie’s frights are a mixed bag. At their best, they’re superb at evoking a sense of incomprehensible horror such as one finds in the works of H. P. Lovecraft. Indeed, Annihilation has been likened to Lovecraft’s 1927 short story “The Colour Out of Space”—as well as its numerous film adaptations—in which a life form brought to Earth on a meteorite wreaks madness and all manner of physical deformities upon the wildlife and human residents of a tract of Massachusetts woodland. (Unlike Annihilation’s alien, however, the being in that tale decimates its surroundings rather than creating something new from them.) The film also contains some very effective Cronenberg-esque body horror. However, not all the scares arise naturally from the plot and the characters; there are some monster attacks and shoot ’em up scenes that belong in a less lofty movie, and which are nowhere to be found in the book.

Beyond its similarity to the Lovecraft story (and despite VanderMeer stoutly denying he was influenced by either of the following two works), Annihilation also has obvious echoes of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s 1972 novel Roadside Picnic and its 1979 movie adaptation, Stalker. These also involve journeys through a restricted zone rife with strange mutations and inexplicable phenomena brought on by contamination left by an extraterrestrial presence.

Annihilation’s screenwriter and director is Alex Garland, whose previous film was another landmark of intelligent sci-fi filmmaking—and his directorial debut, no less—2014’s Ex Machina. With Annihilation, he takes great liberties with his source material, changing much of the plot, premise and thematic emphasis. The film has more human connection, more emotional interplay among the characters, than the novel does. (The book’s characters don’t relate; they’ve completely shed their names and pasts.) The book begins in medias res and bypasses much of its backstory, whereas the film starts more conventionally, with a full act of setup that relies on clichés such as a getting-to-know-you session between Lena and her future fellow expeditioners and tearful flashbacks to Lena’s personal drama that led her to agree to the mission. Neither version of the story is superior, really; they’re more like “refractions” of a single underlying inspiration.

The novel repeatedly stresses the pristineness of Area X. It’s a region that has managed, even if by otherworldly means, to beat back humankind. In the real world, of course, industrial humanity faces pushback from nature in the form of droughts, floods, diminishing returns in soil fertility, emerging infectious diseases and uncountable other threats to human habitat. Clearly, annihilation runs both ways.

Watch Annihilation on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/15222198