By Matt Zoller Seitz

Source: RogerEbert.com

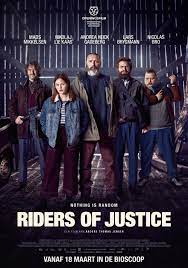

Brutal, sad, funny, and disarmingly sweet-natured, “Riders of Justice” is not so much a revenge movie as a movie about revenge. That might seem like a distinction without a difference until you get to the end of this surprising feature from writer/director Anders Thomas Jensen (“After the Wedding,” “Red Road,” “The Salvation“) and look back on every place that it has taken you.

The story starts a few days before Christmas in Estonia. A girl walking along a holiday-decorated street with her grandfather spots a red bicycle offered for sale by a street vendor but asks for a blue one instead. The vendor is part of a crime ring and calls an associate, who steals a blue bike belonging to Mathilde (Andrea Heick Gadeberg), which causes Mathilde’s mother Emma (Anne Birgitte Lind) to have to pick her up at the train station, only to have their car fail to start, which causes them to take a commuter train home. A statistics and probability expert named Otto (Nikolaj Lie Kaas) gives the girl’s mother his seat, and shortly after that, a freight train smashes into the commuter train and several passengers are killed, including Mathilde’s mother and a tattooed, bald, scowling fellow who was supposed to testify against a fearsome gang, Riders of Justice. Otto saw another man get off the train before the crash, oddly dropping a full beverage and a nearly uneaten sandwich in the trash on his way out, and becomes convinced that the crash was an assassination and the other victims were collateral damage. As it happens, Mathilde’s father is a stony-faced soldier named Markus (Mads Mikkelsen, a frequent leading man for the writer/director).

If this were almost any other movie, you’d be able to write the rest of this review yourself. But you soon figure out that this is not the sort of film that sets up the standard elements and switches to autopilot. For one thing, Jensen makes Otto not merely the messenger who sets the tale in motion and then disappears, but a crucial second lead, and part of a trio filled out by a fellow probability expert named Lennart (Lars Brygmann), whose secret manias and aversions are a constant source of plot complications; and a tightly wound, emotional computer hacker named Emmenthaler (Nicolas Bro). All three characters are written and performed with such skill that they form a comedy trio: a motor-mouthed intellectual answer to the Three Stooges. Like Mathilde, Markus, and everyone else who passes in front of Jensen’s viewfinder, Otto, Lennart and Emmenthaler are given endearing backstories that feed into the script’s fascination with fate, chance, justice, karma, and other subjects rarely discussed in films where the hero is a scary bald dude who can snap a man’s neck like a shingle.

“All events are products of a series of preceding events,” Otto tells an assembled panel of corporate clients who reject an algorithm he and Lennart are trying to sell them. “Because we often have insufficient data, we categorize events as coincidences.” His statement echoes through later scenes, including the church service where Mathilde’s mother and Markus’s wife is laid to rest. “When miracles happen,” the priest says, “we often attribute a divine character to them. However, when lightning strikes, when tragedy becomes reality, we have a hard time assigning a return address, and thus we refer to it as coincidence.” Once the stooges enter Markus’ life, bloodshed follows, but not in a lockstep, predictable way, thanks to the pinball-machine collisions of all the strong personalities involved (particularly Markus’s; he’s both hot-tempered and lethal, not an ideal combination).

The big question here is whether the train crash was a premeditated crime or the culmination of a series of things that quite simply happened. A large part of the charm of “Riders of Justice” (what an ironic title, in retrospect!) comes from the way that it keeps us guessing as to what side of the equation, so to speak, it’ll come down on, or whether it’ll take a position at all. What are we to make, for instance, of a seemingly precise calculation by Otto that the odds of that crash with that outcome were 234,287,121 to one? Or, for that matter, the movie’s wry awareness that no matter how bad things get, they could always be worse? “Only thing is, after all this crap, it’s unlikely more is going to happen,” Mathilde tells Otto. “That’s not how things work,” Otto replies. “A lot of awful things can happen in your life.”

Plots like the one that drive “Riders of Justice” tend to appear in crash-and-burn action thrillers wherein a curtain-raising death or atrocity is there to give the hero (or heroes) a pretext to embark on a spectacular and largely guilt-free rampage, stacking up bodies like firewood. Jensen and his cast and crew go in a different direction, creating a cast of main characters (and several colorful minor characters) with complex, contradictory psychologies that are unveiled a layer at a time, each revelation informing our understanding of what they did in a prior scene, or what they may be capable of later on. It’s hard to imagine the improvisatory, digressive, character-focused filmmaker Mike Leigh (“Secrets and Lies“) making a revenge thriller, but if he did, it might look like this. Sometimes the tangents are so out-of-nowhere, and are developed in such detail, that you and the characters sorta forget about the vengeance thing, which is the entire point.

This is a film that teaches you how to watch it. Once you’ve gotten acclimated, you understand that when a major character makes a decision that seems massively stupid—or simply counter to their self-interest—it’s always rooted in a traumatic past incident or secret, and they had no conscious control over it: it was something that had to happen, thanks to how they’re wired. Mikkelsen, the most still and reactive performer, seems a granite-faced question mark until you spend a bit of time with his character and understand the origins of his stoicism as well as his eruptions of fury. Unexpected connection points are made between him and the stooges and, more pointedly, between Mathilde and Emmenthaler, who are both sensitive about their weight; and Mathilde, Otto and Markus, who have a specific type of loss in common, and fill voids in each other’s lives.

Any of these characters could’ve been the main character in his or her own project, so attentive is the screenplay to the nuances of personality. Emmenthaler, especially, is one of the great secondary characters in action thrillers, up there with Al Powell from the original “Die Hard“—a sensitive man who sheds an angry tear when a friend makes fun of his weight, and has clearly been carrying around an unexploded bomb of suppressed rage throughout his life. He’s the first of the stooges to ask for weapons training.

But even that thread doesn’t go the way you anticipate, because this is a genre picture in which story is driven by characterization rather than the other way around. Not only are there no easy answers, the film goes out of its way to make you think it’s going to tie something off neatly, only to confound you by asking, “What would happen if these characters actually existed?” and doing that instead.

“Did a therapist write this?” is not a sentence once expects to see in one’s notes on a movie where Mads Mikkelsen guns men down with an assault rifle. But it’s consistent with the apparent mission statement of this odd, beguiling film, which is filled with philosophical, theological, moral, and ethical notions (and takes care to distinguish between them) and that weaves images of churches and snippets of religious chorales throughout its running time, as if to remind us of the Christian ideals of grace, healing, and redemption that, for many characters, remain just out of reach. The movie’s contextual scaffolding is constructed with such care that when a character insists that chess is the only game ever invented where luck isn’t a factor, your instinct is to think, “Is that true?” It is, and it isn’t. The closest Jensen gets to summing everything up is Mathilde’s statement that life “is just easier when there’s someone you can get mad at.”

What are we left with? In the best of all possible worlds, a line from Otto, offered when the gang is en route to a bloody showdown: “Let’s get this over with as a team so we can go home and eat banana cake.”

____________________

Watch Riders of Justice on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/12898202