Category Archives: Video

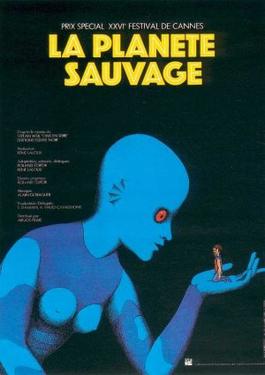

Saturday Matinee: Fantastic Planet

Surrealism and political critique in the animated medium: Fantastic Planet (1973)

By Dan Stalcup

Source: The Goods Firm Reviews

Coming from the “Panic Movement” surrealist art collective is one of the most bizarre animated films of all time: Fantastic Planet, a French-Czech production by director/co-writer René Laloux and co-writer/production designer Roland Topor.

With its title, Fantastic Planet sounds like it should be a cheesy sci-fi flick, and in some ways, it is. (The French title, La Planète sauvage, is much more pleasing.) But this is something much more insular and experimental than most genre films of the era. Thanks to its distinctive pencil-sketched, cutout animation technique (also seen in Monty Python interludes), the film has the look of a history or biology book come to life. The grotesqueries depicted have a diagrammatic, almost clinical look to them, making every alien and bit of worldbuilding feel all the more strange.

Fantastic Planet chronicles a far future when humans have been transplanted to the distant planet Ygam by giant blue aliens with red bug eyes called Draags (or, in some translations, Traags). There, humans serve the role of something resembling a rodent or small dog: occasionally domesticated by Draags, occasionally living in wild colonies as feral creatures. The humans on Ygam are called “Oms” by the Draags. They’re mostly viewed as harmless by the aliens, but often casually exploited and exterminated when convenient.

The story follows Terr, an orphaned human/Om, who is adopted by a Draag, but escapes before organizing an resistance to the giant aliens. Terr’s life has a vaguely mythological arc to it, further enhancing the sense the we’re witnessing some passed-down story. The entire telling is detached and emotionless — when Terr’s mother or compatriots die, there is no mourning or reaction, just a progression to the next item of the story. It’s disquieting.

What really makes Fantastic Planet so bizarre and unforgettable is the depiction of the alien life and planet: flora and fauna that look like something out of a fever dream or acid trip. The ground shifts into squirming intestines; a hookah bar causes the inhabitants to meld into a blur; twirling headless statues perform a mating ritual. It’s baroque and occasionally whimsical; half Dr. Seuss, half Salvador Dali.

Despite the strangeness of the imagery, the film avoids slipping into an all-out dissociated psychedelic trip thanks to its linear and straightforward narrative. This, paradoxically, makes everything feel even more alien: The story takes logical, coherent leaps, but the images and details within are so nonchalantly unearthly. It’s a dizzying juxtaposition.

The story is clearly allegorical: Animal rights is an obvious interpretation given the way that humans are chattelized. It’s not hard to squint and see anti-racism or anti-imperialism in its parable, either — any scenario where the majority or oppressors are negligent, systemic participators rather than active aggressors would fit.

There’s also a lot of coming of age imagery in the film, blown out into absurdism. The semi-comprehending way the humans perceive the Draag world is not too detached from the way kids see the adult world: full of obtuse rituals and norms. Plenty of the designs are charged with phallic and sexual imagery (not to mention casual nudity), but it’s secondary to the overall sweep of the visual invention of the film.

In the half century since its release, Fantastic Planet has become a cult legend, even inducted into the Criterion Collection — one of only a few animated films with the honor. According to Letterboxd, it’s among the most popular films of 1973. I can’t say I blame cinephiles out there. Even at 72 minutes, Fantastic Planet is a bit exhausting, but it’s such a unique and evocative experience that it is essential viewing. At least for weirdos like me.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: The History of the World Backwards

Source: Wikipedia

The History of the World Backwards is a comedy sketch show written and starring Rob Newman. It is a mock history programme set in an alternative world where time flows forwards whilst history told backwards. In other words, if you were born in 2007, you would be 60 years old in 1947. All the major historical events happen backwards, so for example, Nelson Mandela enters jail a Spice Girls fan, and comes out as a terrorist intent in overthrowing the state. There are several recurring themes, such as the “Technology collapse”, where scientific discoveries are lost, forgotten or made unworkable.

It was shown on BBC Four, starting on 30 October 2007, and later shown on BBC Two. It was Newman’s first television project in 14 years.

Two for Tuesday

First Post-Crash Day Fully Conscious

The first group I encountered on my first day of full consciousness post-crash was a team of various medical professionals. A nurse recorded my vital signs while a doctor assessed my cognitive health through a series of questions which I answered by nodding or shaking my head.

A couple of people from the surgical team focused on the extent of my spinal cord injuries, asking if I was able to feel or move various parts of my arms and legs. I was able to feel everywhere, though in a tingly and imprecise way, similar to how one’s arms or legs feel “asleep” from lack of circulation. I could definitely feel a sense of touch, but it seemed to emanate not from the surface of the skin but from a layer beneath. As expected, I couldn’t move anywhere below the shoulders while areas touched on my arms were felt on corresponding areas of phantom limbs above my chest.

Lastly, a specialist investigated my emotional state through another round of questions including if I felt depressed or had suicidal thoughts. This line of questioning seemed absurd at the time for how self-apparent the answers should be. It’s inconceivable that anyone newly quadriplegic would not be depressed. Likewise, any sane person who loses movement of all limbs as well as loss or impairment of numerous internal bodily functions would be lying if they denied having suicidal ideation even fleetingly.

That being said, I nodded in agreement about being depressed but shook my head to signal “no” to the question about suicide. I didn’t want or need suicide counseling and even if I were seriously suicidal, what could I do about it? But my main motive for lying was the possibility that my family would find out. I imagined how they may have experienced trauma from witnessing the trauma I went through, and how much they’d want me to survive. It would hurt them to know they wanted me alive more than I did at the time. There are moments when I still have such thoughts, particularly when my wife and I experience economic setbacks related to my injury, but the emotional impact suicide would have on loved ones is enough to keep the thoughts ephemeral and in the realm of speculation.

As if conjured by thoughts and memories, my wife Danielle and mother Florence arrived soon after, looking just as worried as I expected.

Saturday Matinee: Homecoming

By Michael Gingold

Source: Fangoria

Part of the appeal of Masters of Horror has been the chance to see things on this Showtime series that you won’t see anywhere else on television. So far, that has mostly meant explicit gore, nudity and sexuality, which is all fine and well. But Joe Dante’s Homecoming, premiering December 2, treats us to sights that are not only unique in the TV horror genre, but have been off-limits anywhere else on the tube as well. Like, f’rinstance, rows of flag-draped coffins bearing the bodies of dead soldiers killed in a Mideast war.

Yes, Dante is back in horror-satire mode, and this time he and screenwriter Sam Hamm (adapting the short story “Death and Suffrage” by Dale Bailey) are directly taking on a target that the rest of TV-drama-land and mainstream Hollywood has heretofore largely danced around. The result is as pointed, clever and blackly amusing as anything the genre has seen in ages, a perfect example of horror’s ability to address subjects too touchy to deal with in other genres. It also takes the political subtext of George A. Romero’s Dead series and puts it right up in the forefront, without becoming preachy with its message. Dante and Hamm manage the tricky balancing act of shining a harsh light on current events without losing sight of the fact that they’re telling a horror story first and foremost.

Hamm’s script takes place in the near future, specifically 2008, when a certain Republican president is running for re-election and a war he duped the nation into fighting still rages on. The central characters are campaign consultant David Murch (Jon Tenney) and right-wing author Jane Cleaver (Thea Gill), who has written a popular book attacking the “radical left”—any resemblance to Ann Coulter is, uh, purely coincidental. After meeting on a dead-on parody of an issues-oriented talk show (Terry David Mulligan is perfect as the host), the two find themselves politically and romantically attracted—but their world is shaken up when the dead begin returning to life. Not all the deceased, mind you, just those who were killed in that particular overseas combat, and they’ve got a particular—pardon the pun—ax to grind. It’s an extrapolation of the Vietnam-era ghoul film Deathdream to the nth degree—the image of the first revived corpse pushing its way out from under the Stars and Stripes that cover its casket is the most pointed and arresting image the genre has recently offered.

No more should be said about the plot particulars of Homecoming, which is packed with wonderful details and images; given a document to read, a zombie missing an eye puts on a pair of glasses with a shot-out lens. The way in which Dante and Hamm keep the story twists coming, never losing steam or running in place thematically or dramatically, is kind of breathtaking; every scene has a revelation or line of dialogue that adds new dimension to either the story or the satire. The actors (also including Dante regular Robert Picardo as a political advisor with a secret of his own) adopt just the right tone of straight-faced earnestness, selling every line and never winking at the camera. The behind-the-scenes craftspeople do a good job of substituting Vancouver locations for the D.C. area (this is also the most expansive-looking Masters yet), and Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger contribute undead makeups that get the points across (like that eyeless ghoul) without being showy.

As the film goes on and we learn more about the characters (particularly Murch), Homecoming’s antiwar message gains new levels of resonance, and it comes to a stirring and completely apt conclusion that perfectly ties up the assorted story threads. And even though horror fans are the species of television viewer least likely to be conservative, you don’t get a sense of preaching to the converted here; the writing and filmmaking are so sharp, even some red-staters might respond to the material. For the second year in a row, a satirical zombie project stacks up as the year’s best horror production; here’s hoping someone in Hollywood notices, and gives Dante a shot at a feature that will show off the skills that, on this evidence, are only becoming sharper with time.