Category Archives: Video

Saturday Matinee: The Adjustment Bureau

By Richard Propes

Source: The Independent Critic

The good news is that The Adjustment Bureau is better than it looks.

Based upon a novel by Philip K. Dick, The Adjustment Bureau stars Matt Damon as a man who gets a glimpse at what fate has in store for him and decides that he wants something different. On the brink of winning a seat in the U.S. Senate, Damon’s David Norris is faced with defying fate and chasing beautiful ballet dancer Elise Sellas (Emily Blunt) under, across and all around New York if they are to have any chance of being together.

Now then, back to that godawful movie poster. It sucks, doesn’t it? It made me NOT want to see the film. The movie poster made put off seeing The Adjustment Bureau as long as humanly possible and I don’t even pay to see most films.

Philip K. Dick, the writer of the original source material for films such as The Blade Runner, Minority Report and Total Recall, is far more known as a sci-fi than a romantic writer (Duh!). However, the strength of The Adjustment Bureau lies in the romance and the chemistry between David and Elise. The buttoned-down David and the wild child Elise are not only cute together, but Damon and Blunt have a strong chemistry together that allows this film to work far better than one might expect. The two meet at a Waldorf-Astoria dinner in what is obviously a pre-destined meeting arranged by Harry (Anthony Mackie) and Richardson (John Slattery), two fedora-laden mysterious guys whom we learn are essentially angels whose specific assignments are to ensure that fate takes its course by “adjusting” events, relationships and experiences to ensure it all lines up as it’s supposed to line up. The problem is that once David and Elise have their initial meeting, that’s it. No more. Nadda.

Well, unless, David can change the course of fate.

In fairness to Dick, The Adjustment Bureau isn’t exactly faithful to its source material as much as it takes that central concept and creates another world out of it. This film shouldn’t necessarily have you running off to devour Philip K. Dick’s writings, and to do so will likely only end in disappointment this time around.

All of this could be remarkably campy and silly if not for the convincing romance of Damon and Blunt, along with the weighty and surprisingly impactful performance of Terence Stamp as the superior of Harry and Richardson who adds tremendous gravitas to the entire affair.

Nolfi, who penned The Bourne Ultimatum, makes his directing debut here and while it’s far from flawless it’s certainly admirable enough given the complexity of the material to ensure he will get a second shot at the big screen. While the film’s final third very nearly derails the entire thing, Nolfi manages to keep it afloat just enough that audiences will likely leave the theatre thinking this was a couple of hours well spent.

Matt Damon continues to widen his range, having exhibited gifts recently for everything from action to comedy to westerns and thrillers. While he doesn’t excel here, he most assuredly convinces and he’s strong enough in the romantic department to sell the vast majority of the film. There is an argument that the romance is noticeably light on actual emotion, however, this may very well depend upon how you take the somewhat more stoic romanticism of Damon. The nearly always dependable Emily Blunt shines as well, an intriguing blend of romantic spark and sci-fi sizzle. Terence Stamp steals virtually all of his scenes, seemingly embracing his best role in years.

The Adjustment Bureau would have been a far more successful film as a romantic drama with light elements of action/sci-fi, but too often it seems as if Nolfi feels compelled to tip his hat to Philip K. Dick or Bourne or somebody. The result is a film that bounces once too often between flimsy and weighty, never quite deciding what kind of film it really wants to be. The Adjustment Bureau is far better than nearly anyone will expect given its misguided trailer and simply awful movie poster, but just about the time the audience adjusts to a rock solid romantic drama Nolfi nudges us back towards where our cinematic fates must want us to be.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: The Killing

By Jessica Schneider

Source: automachination

Rare is it that a heist film could yield success through failure. No, I am not talking about the film itself, as The Killing is a near-perfect suspense noir that in many ways transcends its genre, but rather that this perfectly plotted undertaking not only goes awry but still satisfies its viewers. Too often audiences are spoon-fed the suspense, wherein we witness the anti-hero tackle the battle through luck and cleverness, only to get away with it in the end. This, we’ve been trained to believe, is the only way to indulge an audience. Well, Kubrick killed all that with this film (no pun). Indeed, there is no grand sigh at the film’s end.

As his third full-length feature, Stanley Kubrick’s first two films contained varying degrees of quality that, despite their convention, were needed for him to achieve the tautness herein. Finishing at 84 minutes, with the use of perfunctory voiceover, the tone is unemotional, detached. (Rendered by radio announcer Art Gilmore, his voice is 180 from the later 1990s trailers that begin with, ‘In a world…’) Throughout, every move is plotted and carefully crafted. Roger Ebert noted this in his review and correlated the film’s intricacy with that of Kubrick’s chess ability. “The game of chess involves holding in your mind several alternate possibilities. The shifting of one piece can result in a radically different game,” Ebert says.

While the characters do serve as pieces that move the plot—their individuality is not so important given their archetypal nature. George is a gullible, dopey husband who is married to his manipulative, money-hungry wife Sherry who is engaging in an affair with a loser named Val. Johnny (Sterling Hayden) is the plan’s executor who remains steadfast and pugnacious when it suits him, and Nikki, who is paid five grand for rubbing out a horse from the sidelines, is a dope who resorts to racism before he too gets shot while seated within his sports car. We meet the other characters upon being told what their agreements are, and each learns his role as The Killing unfolds—careful deliberation and participation within every motive.

Based on the novel Clean Break by Lionel White, one cannot help but wonder if Kubrick took a mediocre book and made it into a well-executed masterwork. (The Shining, anyone?) Given I have not read the novel, I cannot comment, but The Killing is not only a brilliant title but one that works on both the literal and literary levels. Rather, this is a film about controlled risk and those who wish to engage in it. After all, one can’t be a gambler if one doesn’t love risk, and those who frequent the tracks are most definitely not doing it because of their love of horses.

The character of Johnny, rendered by Sterling Hayden, is effective as Hayden himself who, despite moving cautiously and aggressively, carries his weapon in a large flower box. (Which James Cameron would later utilize in Terminator 2: Judgment Day.) When Johnny finally manages to obtain the money, the bills are treated haphazardly, as many fall to the side of the wide laundry bag. Later, when he stuffs the bills into a large suitcase, the same occurs. It’s as though the prize itself isn’t worth the care and caution of the execution—is it merely about the love of the chase or the love of the dollar bill? How does one operate amid $2 million in cash? Note the final scene at the airport and you will see what I mean.

Criterion is featuring what they call ‘50s Kubrick,’ which consists of four films—his final being his great early achievement, Paths of Glory. Kubrick was only 28 when he directed The Killing and yet this has all the hallmarks of a mature, coherent film. While it does not reach the great emotional depths of the Kirk Douglas classic, The Killing is a masterwork of form and storytelling, and does not, for a moment, hesitate. If you want a film with no fat—this is it. As Ebert eloquently notes, ‘The writing and editing are the keys to how this film never seems to be the deceptive assembly that it is, but appears to be proceeding on schedule, whatever that schedule is.’

Indeed, schedules. The characters punctually do make their time, albeit not always successfully. As example, Nikki proves himself a successful sharpshooter who only gets his demise shortly afterwards. Who are we rooting for, anyway? Should we even care? While I plan to review all four of Kubrick’s ’50s films, I watched The Killing one weekend when I needed something detachable and unemotional. This is not to imply I didn’t care—quite the contrary. Rather, I needed something intricate, and something to study. This, coupled with my love for film noir, deemed it the perfect film for this occasion.

As I noted in my review regarding Kubrick’s first two films, he had to undergo patchwork mediocrity to reach his later ability. Ironically, on the same day of my re-watching The Killing, I also re-watched the 1988 film Die Hard, which is a decently executed thriller with all the ostentatious special effects and annoying character quips. There is no real depth, only a handful of good exchanges, and the contrast between the two films exists within the intelligence—The Killing most certainly has dumb characters, but the mind behind them never deviates from skill. And because The Killing relies heavily on the unfolding of events over the internal doubts of any one character, this is what ranks this film as great, albeit within the noir genre.

The final scene is one to not go overlooked, as Johnny appears at the airport with his wife Fay, and upon not being allowed to carry his suitcase on the plane, he is forced to check it. It is as though we have been waiting for this moment—when the suitcase accidentally opens, and the bills fly about like lost black and white birds. Johnny can’t escape, as the police are onto him. When Fay tells him to run, he responds with, ‘What’s the difference?’ For once, he is without a plan and so he turns around, helpless. The men exit the building and the film ends before they approach him. Johnny, while no longer in control, still maintains his cool. Like losing a game of chess, he will inevitably be rethinking his moves while in jail (presumably) and wondering what he could have done better. Perhaps not booking a flight from California to Boston with the evidence in hand might be a good start.

Two for Tuesday

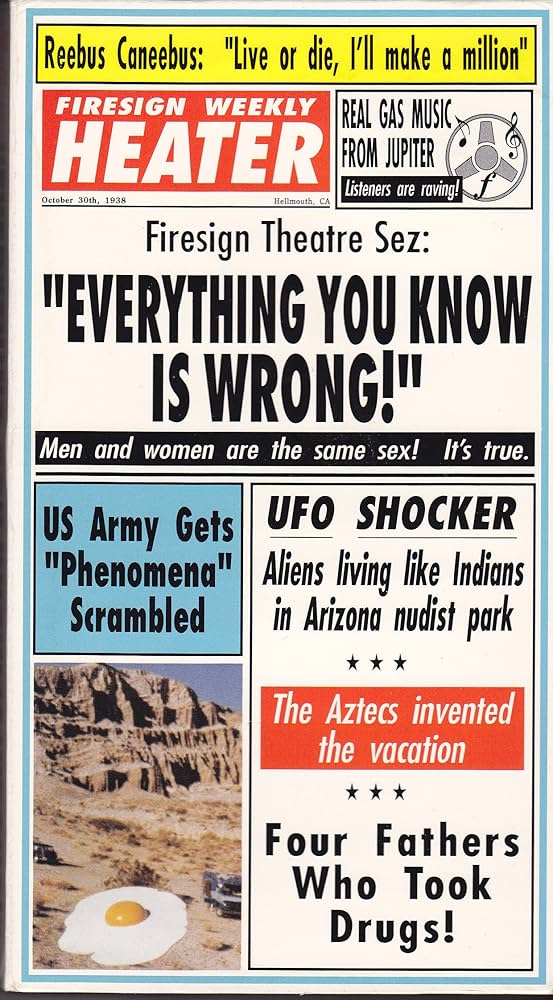

Saturday Matinee: Everything You Know Is Wrong

Source: Wikipedia

Everything You Know Is Wrong is the eighth comedy album by the Firesign Theatre. Released in October 1974 on Columbia Records, it satirizes UFO conspiracy theories and New Age paranormal beliefs such as Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods and claimed psychic Uri Geller, which achieved wide public attention by that time.

After the album was recorded, a movie version was made, with the group lip-syncing to the album. The Don Brouhaha scene from side one, Cox’s side two teaser, and Nino Savant’s lecture on “Holes” from side two, are not included in the video. The cinematographer was Allen Daviau, who later filmed E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. (UPC barcode 735885 100131.) The group showed the film at Stanford University and took questions and answers.The film was released on a VHS format videotape in 1993 by The Firesign Theatre. (UPC barcode 735885 100131.) It was released on DVD in 2016. (UPC barcode 824818 000386.)

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Night of the Hunter

By Roger Ebert

Source: RogerEbert.com

Charles Laughton’s “The Night of the Hunter” (1955) is one of the greatest of all American films, but has never received the attention it deserves because of its lack of the proper trappings. Many “great movies” are by great directors, but Laughton directed only this one film, which was a critical and commercial failure long overshadowed by his acting career. Many great movies use actors who come draped in respectability and prestige, but Robert Mitchum has always been a raffish outsider. And many great movies are realistic, but “Night of the Hunter” is an expressionistic oddity, telling its chilling story through visual fantasy. People don’t know how to categorize it, so they leave it off their lists.

Yet what a compelling, frightening and beautiful film it is! And how well it has survived its period. Many films from the mid-1950s, even the good ones, seem somewhat dated now, but by setting his story in an invented movie world outside conventional realism, Laughton gave it a timelessness. Yes, the movie takes place in a small town on the banks of a river. But the town looks as artificial as a Christmas card scene, the family’s house with its strange angles inside and out looks too small to live in, and the river becomes a set so obviously artificial it could have been built for a completely stylized studio film like “Kwaidan” (1964).

Everybody knows the Mitchum character, the sinister “Reverend” Harry Powell. Even those who haven’t seen the movie have heard about the knuckles of his two hands, and how one has the letters H-A-T-E tattooed on them, and the other the letters L-O-V-E. Bruce Springsteen drew on those images in his song “Cautious Man”:

“On his right hand Billy’d tattooed the word “love” and on his left hand was the word “fear” And in which hand he held his fate was never clear”

Many movie lovers know by heart the Reverend’s famous explanation to the wide-eyed boy (“Ah, little lad, you’re staring at my fingers. Would you like me to tell you the little story of right-hand/left-hand?”) And the scene where the Reverend stands at the top of the stairs and calls down to the boy and his sister has become the model for hundred other horror scenes.

But does this familiarity give “The Night of the Hunter” the recognition it deserves? I don’t think so because those famous trademarks distract from its real accomplishment. It is one of the most frightening of movies, with one of the most unforgettable of villains, and on both of those scores it holds up as well after four decades as I expect “The Silence of the Lambs” to do many years from now.

The story, somewhat rearranged: In a prison cell, Harry Powell discovers the secret of a condemned man (Peter Graves), who has hidden $10,000 somewhere around his house. After being released from prison, Powell seeks out the man’s widow, Willa Harper (Shelley Winters), and two children, John (Billy Chapin) and the owl-faced Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce). They know where the money is, but don’t trust the “preacher.” But their mother buys his con game and marries him, leading to a tortured wedding night inside a high-gabled bedroom that looks a cross between a chapel and a crypt.

Soon Willa Harper is dead, seen in an incredible shot at the wheel of a car at the bottom of the river, her hair drifting with the seaweed. And soon the children are fleeing down the dream-river in a small boat, while the Preacher follows them implacably on the shore; this beautifully stylized sequence uses the logic of nightmares, in which no matter how fast one runs, the slow step of the pursuer keeps the pace. The children are finally taken in by a Bible-fearing old lady (Lillian Gish), who would seem to be helpless to defend them against the single-minded murderer, but is as unyielding as her faith.

The shot of Winters at the bottom of the river is one of several remarkable images in the movie, which was photographed in black and white by Stanley Cortez, who shot Welles’ “The Magnificent Ambersons,” and once observed he was “always chosen to shoot weird things.” He shot few weirder than here, where one frightening composition shows a street lamp casting Mitchum’s terrifying shadow on the walls of the children’s bedroom. The basement sequence combines terror and humor, as when the Preacher tries to chase the children up the stairs, only to trip, fall, recover, lunge and catch his fingers in the door. And the masterful nighttime river sequence uses giant foregrounds of natural details, like frogs and spider webs, to underline a kind of biblical progression as the children drift to eventual safety.

The screenplay, based on a novel by Davis Grubb, is credited to James Agee, one of the icons of American film writing and criticism, then in the final throes of alcoholism. Laughton’s widow, Elsa Lanchester, is adamant in her autobiography: “Charles finally had very little respect for Agee. And he hated the script, but he was inspired by his hatred.” She quotes the film’s producer, Paul Gregory: “. . . the script that was produced on the screen is no more James Agee’s . . . than I’m Marlene Dietrich.”

Who wrote the final draft? Perhaps Laughton had a hand. Lanchester and Laughton both remembered that Mitchum was invaluable as a help in working with the two children, whom Laughton could not stand. But the final film is all Laughton’s, especially the dreamy, Bible-evoking final sequence, with Lillian Gish presiding over events like an avenging elderly angel.

Robert Mitchum is one of the great icons of the second half-century of cinema. Despite his sometimes scandalous off-screen reputation, despite his genial willingness to sign on to half-baked projects, he made a group of films that led David Thomson, in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, to ask, “How can I offer this hunk as one of the best actors in the movies?” And answer: “Since the war, no American actor has made more first-class films, in so many different moods.” “The Night of the Hunter,” he observes, represents “the only time in his career that Mitchum acted outside himself,” by which he means there is little of the Mitchum persona in the Preacher.

Mitchum is uncannily right for the role, with his long face, his gravel voice, and the silky tones of a snake-oil salesman. And Shelly Winters, all jitters and repressed sexual hysteria, is somehow convincing as she falls so prematurely into, and out of, his arms. The supporting actors are like a chattering gallery of Norman Rockwell archetypes, their lives centered on bake sales, soda fountains and gossip. The children, especially the little girl, look more odd than lovable, which helps the film move away from realism and into stylized nightmare. And Lillian Gish and Stanley Cortez quite deliberately, I think, composed that great shot of her which looks like nothing so much as Whistler’s mother holding a shotgun.

Charles Laughton showed here that he had an original eye, and a taste for material that stretched the conventions of the movies. It is risky to combine horror and humor, and foolhardy to approach them through expressionism. For his first film, Laughton made a film like no other before or since, and with such confidence it seemed to draw on a lifetime of work. Critics were baffled by it, the public rejected it, and the studio had a much more expensive Mitchum picture (“Not as a Stranger”) it wanted to promote instead. But nobody who has seen “The Night of the Hunter” has forgotten it, or Mitchum’s voice coiling down those basement stairs: “Chillll . . . dren?”