Documentarian William Greaves’s Restored Civil Rights Political Documentary asks, “What Time is it?”

By Jim Tudor

Source: ZekeFilm

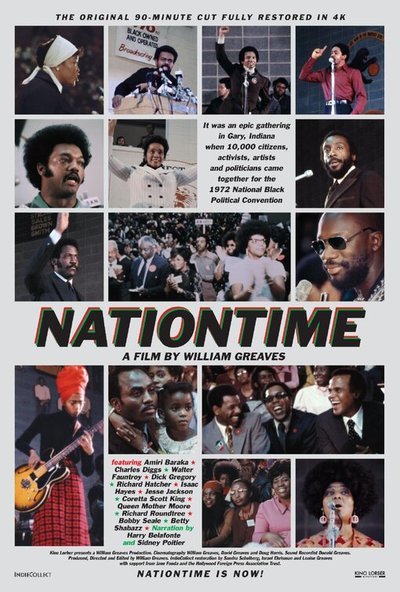

In 1972, the mayor of Gary, Indiana Richard Hatcher welcomed a tremendous gathering of African American leaders, intellectuals, activists and speakers to hold the twentieth century’s first and only National Black Political Convention. Luminaries such as Amiri Baraka, Charles Diggs, Walter Fauntroy, Dick Gregory, Isaac Hayes, Bobby Seale, Harry Belafonte, Coretta Scott King, Queen Mother Moore and Jesse Jackson took the stage in a crowded sports gymnasium in the fired-up interest of promoting “an independent national black agenda”. With over 10,000 in attendance, the gathering seeked to bring together differing factions in the cause of Black advancement in America. More to the point, their goal for the three-day Convention was “unity without uniformity”.

The National Black Political Convention of 1972 was a turning point in the struggle for self determination and equal rights.”

“ The convention adjourned without reaching consensus, and some deemed it a failure.”

“But the cry of ‘Nationtime’ reverberates as America continues to wrestle with its legacy of slavery.

So goes the entirely of the opening text viewed at the start of this newly salvaged presentation of documentarian William Greaves’s Nationtime. Tasked with documenting the convention, Greaves and his crew do just that; the final version of this 1972 film a sort of fly-on-the-wall highlights reel of the event. Those who know Greaves primarily for his 1968 meta-experimental Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One now have this chance to view one of the filmmaker’s works which falls more into his bread-and-butter wheelhouse of African American-issues documentary filmmaking.

It is apparent that Greaves had no additional access to back-room goings-on and behind the scenes drama of the convention, which there apparently was no shortage of. Rather, he and his handful of cameramen are relegated to the same level of observation as anyone in ordinary attendance. As a result, the height of tension- a mass exodus of the contingency from Michigan- occurs with little contextualization. (Greaves’s friend, actor Sidney Poitier, provides occasional narration where needed).

In October of 2020, Kino Marquee released to virtual theaters a black and white version of the newly rediscovered and 4K-restored Nationtime. At least, it was a black and white version that critics were given access to, thereby resulting in some incorrect statements that the film was shot monochrome. We know from this subsequent Blu-ray release that that was not the case. The black and white version is not included on the Blu-ray; Kino Classics instead opting to showcase IndieCollect’s extensive color restoration. The valiant result remains quite visibly imperfect, though this is no doubt the very best it can ever look.

Nevertheless, a film that’s mostly podium-bound political and social speeches can only have so much traction as cinema. Roger Ebert famously said that a film isn’t about what it’s about, but rather how it’s about it. If that’s the case, a film like Nationtime cannot fare tremendously well. Yet, there’s no denying the historical importance of the event documented, particularly in today’s tragic post-George Floyd world. Nationtime (originally called “Nationtime – Gary”, for the town it takes place in) is a major, black-organized event as documented by a black filmmaker. That alone secures it all the credentials it needs in this day and age to rightly present as important.

But “important” and “cinematically compelling” are two different things. Though the speakers at the podium are dynamic in their passion, there’s rudimentary catch-as-catch-can quality to Greaves’s film. It’s an unfortunate showing of seams that often renders the film challenging to stick with.

An informal count reveals that Greaves had no more than five cameras in play, each shooting color film stock. According to a notation at the end of the film, Nationtime was restored in both color and black and white. The latter was apparently an attempt to conceal the irregularities in the footage from one camera to the next. The amateur-esque variations in film stock, lighting, and perhaps exposure are apparent throughout, and unlikely successfully concealed simply by removing color. (Per David Greaves’s audio commentary recollection, he was given some bad advice from Kodak to use a red filter on his own camera, likely contributing to why the finished film was deemed something of a lost cause at the time. Thankfully, today’s color correction technologies have undone that specific gaffe).

The end result is what it is: an ultra-low budget effort financed by Greaves himself. Greaves’s son David, who worked closely with his father and was also there, recalls that outside financing was never secured, though the filmmaker had no intention to not document the event. According to one story on the new bonus features, William Greaves continued manning his camera during Jesse Jackson’s dynamic speech even when he had run out of film, so enraptured he was in that moment.

Indeed, the raw enthusiasm of being there and capturing “the happening” of it all shines through the vast imperfections of the film. Greaves’s knack for knowing and grabbing quality b-roll when he sees it is absolutely apparent. Through the rough-hewn assembly of it all, apt cutaways of engaged faces and fist-waving crowd enthusiasm are the flourishes that shine.

Through it all, in the face of all the racial progress in America that’s yet to be made, Reverend Jesse Jackson’s impassioned call and response of “What time is it?” “Nationtime!” resonates anew for a country still in great need of working things out in terms of equality and corrective justice.

Watch Nationtime on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/movie/nationtime-sidney-poitier/17616062