By Malcolm Harris

Source: Medium

It was explicitly and deliberately a ratchet, designed to effect a one-way passage from scarcity to plenty by way of stepping up output each year, every year, year after year. Nothing else mattered: not profit, not the rate of industrial accidents, not the effect of the factories on the land or the air. The planned economy measured its success in terms of the amount of physical things it produced.

— Francis Spufford, Red Plenty

But isn’t a business’s goal to turn a profit? Not at Amazon, at least in the traditional sense. Jeff Bezos knows that operating cash flow gives the company the money it needs to invest in all the things that keep it ahead of its competitors, and recover from flops like the Fire Phone. Up and to the right.

— Recode, “Amazon’s Epic 20-Year Run as a Public Company, Explained in Five Charts”

From a financial point of view, Amazon doesn’t behave much like a successful 21st-century company. Amazon has not bought back its own stock since 2012. Amazon has never offered its shareholders a dividend. Unlike its peers Google, Apple, and Facebook, Amazon does not hoard cash. It has only recently started to record small, predictable profits. Instead, whenever it has resources, Amazon invests in capacity, which results in growth at a ridiculous clip. When the company found itself with $13.8 billion lying around, it bought a grocery chain for $13.7 billion. As the Recode story referenced above summarizes in one of the graphs: “It took Amazon 18 years as a public company to catch Walmart in market cap, but only two more years to double it.” More than a profit-seeking corporation, Amazon is behaving like a planned economy.

If there is one story on Americans who grew up after the fall of the Berlin Wall know about planned economies, I’d wager it’s the one about Boris Yeltsin in a Texas supermarket.

In 1989, recently elected to the Supreme Soviet, Yeltsin came to America, in part to see Johnson Space Center in Houston. On an unscheduled jaunt, the Soviet delegation visited a local supermarket. Photos from the Houston Chronicle capture the day: Yeltsin, overcome by a display of Jell-O Pudding Pops; Yeltsin inspecting the onions; Yeltsin staring down a full display of shiny produce like a line of enemy soldiers. Planning could never master the countless variables that capitalism calculated using the tireless machine of self-interest. According to the story, the overflowing shelves filled Yeltsin with despair for the Soviet system, turned him into an economic reformer, and spelled the end for state socialism as a global force. We’re taught this lesson in public schools, along with Animal Farm: Planned economies do not work.

It’s almost 30 years later, but if Comrade Yeltsin had visited today’s most-advanced American grocery stores, he might not have felt so bad. Journalist Hayley Peterson summarized her findings in the title of her investigative piece, “‘Seeing Someone Cry at Work Is Becoming Normal’: Employees Say Whole Foods Is Using ‘Scorecards’ to Punish Them.” The scorecard in question measures compliance with the (Amazon subsidiary) Whole Foods OTS, or “on-the-shelf” inventory management. OTS is exhaustive, replacing a previously decentralized system with inch-by-inch centralized standards. Those standards include delivering food from trucks straight to the shelves, skipping the expense of stockrooms. This has resulted in produce displays that couldn’t bring down North Korea. Has Bezos stumbled into the problems with planning?

Although OTS was in play before Amazon purchased Whole Foods last August, stories about enforcement to tears fit with the Bezos ethos and reputation. Amazon is famous for pursuing growth and large-scale efficiencies, even when workers find the experiments torturous and when they don’t make a lot of sense to customers, either. If you receive a tiny item in a giant Amazon box, don’t worry. Your order is just one small piece in an efficiency jigsaw that’s too big and fast for any individual human to comprehend. If we view Amazon as a planned economy rather than just another market player, it all starts to make more sense: We’ll thank Jeff later, when the plan works. And indeed, with our dollars, we have.

In fact, to think of Amazon as a “market player” is a mischaracterization. The world’s biggest store doesn’t use suggested retail pricing; it sets its own. Book authors (to use a personal example) receive a distinctly lower royalty for Amazon sales because the site has the power to demand lower prices from publishers, who in turn pass on the tighter margins to writers. But for consumers, it works! Not only are books significantly cheaper on Amazon, the site also features a giant stock that can be shipped to you within two days, for free with Amazon Prime citizensh…er, membership. All 10 or so bookstores I frequented as a high school and college student have closed, yet our access to books has improved — at least as far as we seem to be able to measure. It’s hard to expect consumers to feel bad enough about that to change our behavior.

Although they attempt to grow in a single direction, planned economies always destroy as well as build. In the 1930s, the Soviet Union compelled the collectivization of kulaks, or prosperous peasants. Small farms were incorporated into a larger collective agricultural system. Depending on who you ask, dekulakization was literal genocide, comparable to the Holocaust, and/or it catapulted what had been a continent-sized expanse of peasants into a modern superpower. Amazon’s decimation of small businesses (bookstores in particular) is a similar sort of collectivization, purging small proprietors or driving them onto Amazon platforms. The process is decentralized and executed by the market rather than the state, but don’t get confused: Whether or not Bezos is banging on his desk, demanding the extermination of independent booksellers — though he probably is — these are top-down decisions to eliminate particular ways of life.

Now, with the purchase of Whole Foods, Bezos and Co. seem likely to apply the same pattern to food. Responding to reports that Amazon will begin offering free two-hour Whole Foods delivery for Prime customers, BuzzFeed’s Tom Gara tweeted, “Stuff like this suggests Amazon is going to remove every cent of profit from the grocery industry.” Free two-hour grocery delivery is ludicrously convenient, perhaps the most convenient thing Amazon has come up with yet. And why should we consumers pay for huge dividends to Kroger shareholders? Fuck ’em; if Bezos has the discipline to stick to the growth plan instead of stuffing shareholder pockets every quarter, then let him eat their lunch. Despite a business model based on eliminating competition, Amazon has avoided attention from antitrust authorities because prices are down. If consumers are better off, who cares if it’s a monopoly? American antitrust law doesn’t exist to protect kulaks, whether they’re selling books or groceries.

Amazon has succeeded in large part because of the company’s uncommon drive to invest in growth. And today, not only are other companies slow to spend, so are governments. Austerity politics and decades of privatization put Amazon in a place to take over state functions. If localities can’t or won’t invest in jobs, then Bezos can get them to forgo tax dollars (and dignity) to host HQ2. There’s no reason governments couldn’t offer on-demand cloud computing services as a public utility, but instead the feds pay Amazon Web Services to host their sites. And if the government outsources health care for its population to insurers who insist on making profits, well, stay tuned. There’s no near-term natural end to Amazon’s growth, and by next year the company’s annual revenue should surpass the GDP of Vietnam. I don’t see any reason why Amazon won’t start building its own cities in the near future.

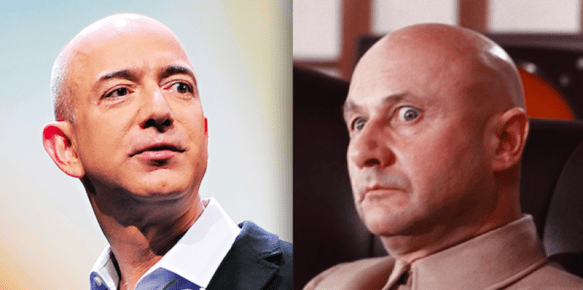

America never had to find out whether capitalism could compete with the Soviets plus 21st-century technology. Regardless, the idea that market competition can better set prices than algorithms and planning is now passé. Our economists used to scoff at the Soviets’ market-distorting subsidies; now Uber subsidizes every ride. Compared to the capitalists who are making their money by stripping the copper wiring from the American economy, the Bezos plan is efficient. So, with the exception of small business owners and managers, why wouldn’t we want to turn an increasing amount of our life-world over to Amazon? I have little doubt the company could, from a consumer perspective, improve upon the current public-private mess that is Obamacare, for example. Between the patchwork quilt of public- and private-sector scammers that run America today and “up and to the right,” life in the Amazon with Lex Luthor doesn’t look so bad. At least he has a plan, unlike some people.

From the perspective of the average consumer, it’s hard to beat Amazon. The single-minded focus on efficiency and growth has worked, and delivery convenience is perhaps the one area of American life that has kept up with our past expectations for the future. However, we do not make the passage from cradle to grave as mere average consumers. Take a look at package delivery, for example: Amazon’s latest disruptive announcement is “Shipping with Amazon,” a challenge to the USPS, from which Amazon has been conniving preferential rates. As a government agency bound to serve everyone, the Postal Service has had to accept all sorts of inefficiencies, like free delivery for rural customers or subsidized media distribution to realize freedom of the press. Amazon, on the other hand, is a private company that doesn’t really have to do anything it doesn’t want to do. In aggregate, as average consumers, we should be cheering. Maybe we are. But as members of a national community, I hope we stop to ask if efficiency is all we want from our delivery infrastructure. Lowering costs as far as possible sounds good until you remember that one of those costs is labor. One of those costs is us.

Earlier this month, Amazon was awarded two patents for a wristband system that would track the movement of warehouse employees’ hands in real time. It’s easy to see how this is a gain in efficiency: If the company can optimize employee movements, everything can be done faster and cheaper. It’s also easy to see how, for those workers, this is a significant step down the path into a dystopian hellworld. Amazon is a notoriously brutal, draining place to work, even at the executive levels. The fear used to be that if Amazon could elbow out all its competitors with low prices, it would then jack them up, Martin Shkreli style. That’s not what happened. Instead, Amazon and other monopsonists have used their power to drive wages and the labor share of production down. If you follow the Bezos strategy all the way, it doesn’t end in fully automated luxury communism or even Wall-E. It ends in The Matrix, with workers swaddled in a pod of perfect convenience and perfect exploitation. Central planning in its capitalist form turns people into another cost to be reduced as low as possible.

Just because a plan is efficient doesn’t mean it’s good. Postal Service employees are unionized; they have higher wages, paths for advancement, job stability, negotiated grievance procedures, health benefits, vacation time, etc. Amazon delivery drivers are not and do not. That difference counts as efficiency when we measure by price, and that is, to my mind, a very good argument for not handing the world over to the king of efficiency. The question that remains is whether we have already been too far reduced, whether after being treated as consumers and costs, we might still have it in us to be more, because that’s what it will take to wrench society away from Bezos and from the people who have made him look like a reasonable alternative.