Witney Seibold Reviews ‘The Visitor’ (1979)

By Witney Seibold

Source: Critically Acclaimed

I first encountered Michael J. Paradise’s “The Visitor” at an after-hours, by-invite-only screening curated by my local video store.

You see: The managers of said video store would, on a weekly basis, acquire whatever 35mm prints they could get a hold of for cheap and/or free. These prints consisted of obscure German comedies, weird sex films, lost genre oddities, sci-fi epics with missing reels, and, in one baffling bout of programming, “My Giant.” Then, in conjunction with a helpful projectionist at the movie theater next door (where I worked at the time), the store managers would invite over employees and friends of employees to view said films, eager to talk aloud in the theater and openly discuss the insanity on screen. These were magical nights of baffling cinematic exploration, and I’m glad to have been invited on several occasions.

It was in this milieu that I was introduced to Michael J. Paradise’s 1979 sci-fi epic “The Visitor,” perhaps one of the most baffling films ever produced. It was such a moving experience that I rushed to my (now long-neglected) criticism blog to review it. That was in 2007. The time has now come to re-visit “The Visitor” and see what new lessons can be learned. Luckily, the film is just as brain-melting as it always was.

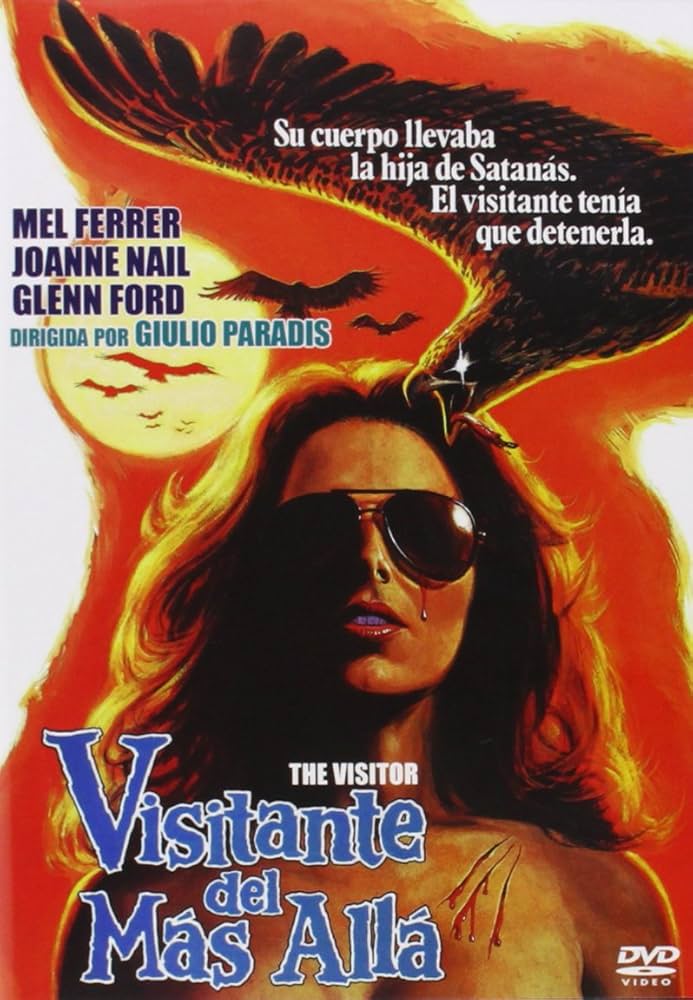

Michael J. Paradise is the nom de cinéma of director Giulio Paradisi, an Italian character actor and assistant director who only made four features in his career (one of which was a crime comedy called “Spaghetti House”). “The Visitor” was his second feature, and, from the looks of it, the most ambitious. Tapping into many of the “2001”-inspired sci-fi trends of the time, Paradisi made a film that sought to tie together the cosmos with spirituality, Jesus with space aliens, and apocalyptic genre tropes with an all-star cast.

“The Visitor” sets its sights on the entire universe, the nature of good and evil, and how humanity is the plaything of warring ancient space deities. The “big questions,” however, are mixed into a psychedelic bouillabaisse of confounding imagery, bad plotting, and weird-ass performances, at least one of which was done entirely under the influence of alcohol. “The Visitor” is insane.

The plot of the film centers on a young girl named Katy (Paige Connor) who is poised to be the next Christ or the next Antichrist, depending on which timeless deity can influence her fastest. On the light side is John Huston and Franco Nero, who oversee an ultra-futuristic space lounge populated by bald children. Nero dispenses Christ-like wisdom while Huston does the legwork; Huston sets up shop on modern-day Earth atop a Los Angeles skyscraper with a cadre of performing space cultists. Many of Huston’s scenes involve his direction of their performance art and his manipulating the stars with his very mind. He wants Katy to become a vessel for – who else? – Yahweh.

On the dark side, we have Lance Henricksen, owner of the Atlanta basketball team, who regularly attends creepy board meetings in a modern high-rise to discuss apocalyptic details with a shadowy cabal of high-powered executives. Henricksen is urged by this cabal (headed by Mel Ferrer) to magically influence young Katy into becoming a vessel for Zatteen, a.k.a. Satan. Katy, meanwhile, has already displayed a propensity for evil: Not only does she have telekinetic powers, but at her birthday party, Katy received a gun as a present (!) and shoots her aunt.

Shelley Winters also appears as a recently-hired nanny for Katy, but I was unsure if she was in the employ of the Huston cult or the Henricksen cult. At the film’s conclusion, she does give a tearful farewell to the Huston character, but that adds no rhyme nor reason. To add a much-needed human element to “The Visitor,” much of the film is seen through the eyes of Katy’s mother Barbara (Joanne Nail), who serves as our protagonist. She will eventually be felled by a gunshot and will spend much of “The Visitor” in a wheelchair.

The above synopsis only emerged in my mind after several viewings of “The Visitor.” While in the midst of actually viewing this Frankensteinian monstrosity, however, one may find themselves totally lost. “The Visitor” takes very long intermissions wherein portentous music pounds at the soundtrack but not much of ultimate consequence happens. The star-manipulating scene mentioned above is neat, I suppose, but it has no influence on the characters or the story as far as I can tell. There is another sequence wherein Katy is particularly at risk at an ice-skating rink, and the film’s poor sense of spatial continuity might have one believing that John Huston is scurrying down 3000 flights of stairs to stop it. At the end of that fateful descent, nothing notable happens.

The most mind-blowing celebrity cameo is provided by Sam Peckinpah who, in 1979, was in dire straits. In 1978, he directed “Convoy,” often seen as the least of his films, and it’s been posited that he accepted make “Convoy” only due to his addictions to booze and cocaine. He appears in one scene of “The Visitor” as Barbara’s ex-husband and Katy’s biological father. Peckinpah’s dialogue appears to have been dubbed, and, as we posited at that midnight screening so many years ago, it may have been because he was too drunk to remember his lines. He certainly seems tipsy and unhappy in his scenes.

In 2007, I was happy to let “The Visitor” melt my brain without much in the way of analysis. It was instantly classified by the midnight audience as a “Holy Fucking Shit” movie, and it still, to this day, enjoys a coveted spot on the “Holy Fucking Shit” shelf at CineFile Video.

In 2018, having now seen more bonkers, psychedelic 1970s sci-fi epics, I have a better context for it. Thanks to “2001: A Space Odyssey,” audiences enjoyed nearly a decade of incredibly ambitious sci-fi movies that sought to unlock the deepest philosophical questions about eternity, humankind’s place in the cosmos, and how our consciousnesses may be a vital piece to a vast, astral puzzle. If one is swallowing tabs of acid while watching Carl Sagan interviews, one could easily conceive of something like “The Visitor.”

I can’t say that the bulk of 1970s psychedelia was necessarily successful – they were big on histrionics but short on actual logic, character, historical theology, filmmaking acumen, or even basic entertainment value – but one can at least admire them for being willing to tip into the surreal to reach something higher. The movies often suck, but I can see why someone might have written something like, say, “God Told Me To” or “Zardoz.” I just couldn’t say how they did.

“The Visitor” will ever remain an oddity, but wow, what a rush! This is one of the crown jewels in baffling psychedelic 1970s freakout cinema and should be shared immediately. Drafhouse Films put out a handsome Blu-ray of it a few years back, and I encourage the purchase of it, sight unseen. I have my copy.

Watch The Visitor on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/kcls/video/13448350