By Richard T. Jameson

Source: Parallax View

[Originally published in Movietone News 36, October 1974]

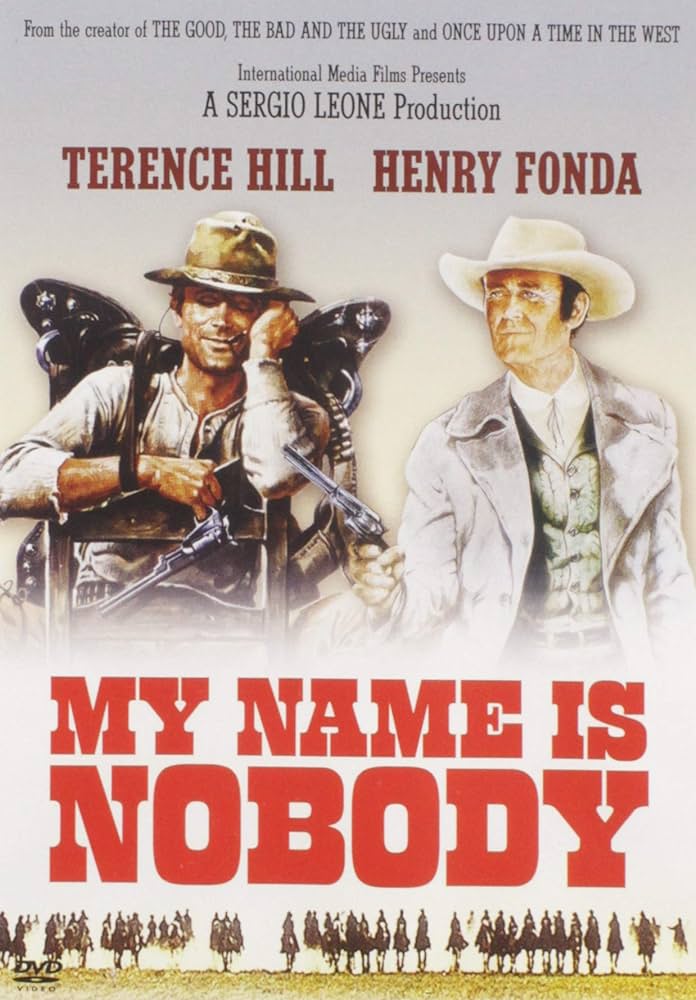

Most people have been writing about My Name Is Nobody as though it were as unequivocally a Sergio Leone film as Once upon a Time in the West, Duck You Sucker, et al.; some reviewers haven’t troubled to mention the existence of Tonino Valerii (who is emphatically given directorial credit twice in the opening titles) while more scrupulous commentators have nodded toward Valerii while acclaiming My Name Is Nobody as “the most producer-directed movie since The Thing.” There’s no mistaking the Leone manner, the Leone themes, and the frequent instances of Leone power and feeling; the protégé has learned the master’s lessons well, and one feels certain he was largely executing Leone’s own detailed plan of the film. I’m sorry I muffed my chance to see Valerii’s own A Reason to Live, a Reason to Die a month or so ago (I loathe drive-ins) because I might have been better prepared to wade in and sort out the fine points of auteurship in the mise-en-scène. There are lapses in the film that mightn’t have occurred—or might have been more decisively compensated for—if Leone’s hand had been at the throttle. But there are also shots, sequences, and literally timeless moments in the movie that do no disservice to the memory of previous Leones—which is to say that My Name Is Nobody contains some of the most extravagantly exciting footage that’s going to appear on movie screens this year.

The greater share of these is concentrated in the opening half hour or so, wherein we encounter Henry Fonda (doing his best and most cinematic work since Once upon a Time in the West) as a legendary gunfighter named Jack Beauregard and Terence Hill as the latest blue-eyed Leone angel with no name whose life-obsession is to see Beauregard top his career with a one-man stand against the Wild Bunch—150 strong. Beauregard, 51 years of age, isn’t interested. He’s engaged in a double-purpose journey: tracking down several men to kill them or save them, we aren’t quite sure for a while—and also aiming himself toward a ship called the Sundowner in New Orleans which will carry him away from his life-and-death career to bookish retirement in Europe. One inevitably becomes aware of career parallels: Ford winding up his cavalry trilogy with Rio Grande—which has the U.S. Cavalry riding out of United States territory to defeat some hostile Indians—and then turning back to the Ould Sod with The Quiet Man; and, of course, Leone himself, who reconstituted the western in the deliriously decadent terms of Italian romanticism and eventually came to America to make his movies, or parts of them: it has been suggested that My Name Is Nobody is his farewell to the genre (it’s at least an arrivederci—he still wants his next picture to be that long-awaited gangster movie Once upon a Time in the United States) and in its verbal explicitness this latest effort is as prosaically academic as Jack Beauregard looks whenever he puts on his wire-templed spectacles.

But if Beauregard/Fonda makes an appropriate “national monument” to build another death-of-the-West-and-western movie around, Terence Hill’s Nobody—despite a splendid introduction—keeps souring the enterprise with his bland blond pretty-boy features and limited, but very insistent, comic repertoire. And, magnificent as some of the visuals are, too many of them lack the elusive but suggestively forceful spatial and spiritual and characterological coordinates of Leone’s own frames. The mesmerizing detail, the comprehensive authority of camera placement and movement in Leone’s own films, inculcates a terrific sense of inevitability, which tends to make a perverse virtue out of his tortuous excuses for plots (all of which—save the one he stole from Kurosawa—boast holes through which the Wild Bunch could ride). When Beauregard refuses to shoot a man whom everyone has expected him to kill, he sardonically apologizes to Nobody for failing to live up to the sterling ideal the younger man believed in: his destiny, he insists, is to quit while he’s still alive. But Nobody says, “Sometimes ya run smack into your destiny on the very road you’re takin’ to get away from it”: Leone/Valerii cuts to a white desertscape through which the Wild Bunch rides like a storm, and we know that, in the space of that cut, Nobody has gone and killed the man Beauregard spared, and the Bunch is riding to avenge him, as dictated by Nobody’s own inscrutable scenario: Jack Beauregard will face those 150 sons-o’-bitches after all.

This had every right to be a throat-clutching moment (and, in fairness, it’s not bad at all), but this happens to be the third time we’ve been treated to such a scene (each set to Morricone’s outrageous version of “The Ride of the Valkyries”) and, unlike the increasingly distinct memory-image that punctuates Once upon a Time or the cumulatively meaningful progression of recollections from Coburn’s past in Duck You Sucker, the effect has diminished through familiarity on our part and a failure on the director’s to make it new again. Similarly, when Beauregard passes a payroll train at sunset a moment later in the film, we recall that a train rather gratuitously wiped a view of Nobody as he attended a western carnival earlier (a scene that is too derivative and too long—the point, indeed, at which the picture breaks down), and this same train will, for no good reason whatsoever, figure in—be present at—Beauregard’s showdown with the Bunch. Such imagistic links have worked beautifully in the past, but here they never resolve into a form with an aesthetic validity in its own right. Indeed, no sequence suffers from failure of formal credibility more crucially than the big shootout, because there is no rational explanation of how Beauregard figures out how to defeat the numerous adversary (not the first time that’s been true in a Leone film—to those films’ glory) and the fatal flaw—the “visual” logic that seeks to stand in for a more conventional rationale—is, in fact, illogical and trivial.

If I’ve gone on too long about some of the shortcomings of My Name Is Nobody, let me assure the reader I’ve deliberately avoided recounting the manifold beauties of those shots and scenes that do work, the breathtaking switches between absurdist comedy and exultant romanticism, the splendors of Morricone’s score (completely integral to the film, as always with Leone-Morricone endeavors) and Ruzzolini’s and Nannuzzi’s cinematography, and the many self-aware allusions to western classics by Leone and others, which possess a resonance that the over-descriptive screenplay occasionally threatens to overwhelm. A hemi-semi-demi-Leone movie is not only better than no Leone movie at all—it’s also better than just about anything else that’s come along lately. Because, after all, who makes films bigger than Sergio Leone’s? Nobody.

____________________

Watch My Name is Nobody on Plex here: https://watch.plex.tv/movie/my-name-is-nobody-1973