Surrealism and political critique in the animated medium: Fantastic Planet (1973)

By Dan Stalcup

Source: The Goods Firm Reviews

Coming from the “Panic Movement” surrealist art collective is one of the most bizarre animated films of all time: Fantastic Planet, a French-Czech production by director/co-writer René Laloux and co-writer/production designer Roland Topor.

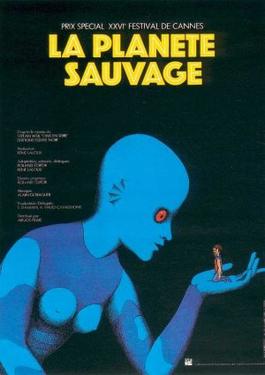

With its title, Fantastic Planet sounds like it should be a cheesy sci-fi flick, and in some ways, it is. (The French title, La Planète sauvage, is much more pleasing.) But this is something much more insular and experimental than most genre films of the era. Thanks to its distinctive pencil-sketched, cutout animation technique (also seen in Monty Python interludes), the film has the look of a history or biology book come to life. The grotesqueries depicted have a diagrammatic, almost clinical look to them, making every alien and bit of worldbuilding feel all the more strange.

Fantastic Planet chronicles a far future when humans have been transplanted to the distant planet Ygam by giant blue aliens with red bug eyes called Draags (or, in some translations, Traags). There, humans serve the role of something resembling a rodent or small dog: occasionally domesticated by Draags, occasionally living in wild colonies as feral creatures. The humans on Ygam are called “Oms” by the Draags. They’re mostly viewed as harmless by the aliens, but often casually exploited and exterminated when convenient.

The story follows Terr, an orphaned human/Om, who is adopted by a Draag, but escapes before organizing an resistance to the giant aliens. Terr’s life has a vaguely mythological arc to it, further enhancing the sense the we’re witnessing some passed-down story. The entire telling is detached and emotionless — when Terr’s mother or compatriots die, there is no mourning or reaction, just a progression to the next item of the story. It’s disquieting.

What really makes Fantastic Planet so bizarre and unforgettable is the depiction of the alien life and planet: flora and fauna that look like something out of a fever dream or acid trip. The ground shifts into squirming intestines; a hookah bar causes the inhabitants to meld into a blur; twirling headless statues perform a mating ritual. It’s baroque and occasionally whimsical; half Dr. Seuss, half Salvador Dali.

Despite the strangeness of the imagery, the film avoids slipping into an all-out dissociated psychedelic trip thanks to its linear and straightforward narrative. This, paradoxically, makes everything feel even more alien: The story takes logical, coherent leaps, but the images and details within are so nonchalantly unearthly. It’s a dizzying juxtaposition.

The story is clearly allegorical: Animal rights is an obvious interpretation given the way that humans are chattelized. It’s not hard to squint and see anti-racism or anti-imperialism in its parable, either — any scenario where the majority or oppressors are negligent, systemic participators rather than active aggressors would fit.

There’s also a lot of coming of age imagery in the film, blown out into absurdism. The semi-comprehending way the humans perceive the Draag world is not too detached from the way kids see the adult world: full of obtuse rituals and norms. Plenty of the designs are charged with phallic and sexual imagery (not to mention casual nudity), but it’s secondary to the overall sweep of the visual invention of the film.

In the half century since its release, Fantastic Planet has become a cult legend, even inducted into the Criterion Collection — one of only a few animated films with the honor. According to Letterboxd, it’s among the most popular films of 1973. I can’t say I blame cinephiles out there. Even at 72 minutes, Fantastic Planet is a bit exhausting, but it’s such a unique and evocative experience that it is essential viewing. At least for weirdos like me.