Inherent Vice: The Very Biased Review

By Joaquin Stick

Source: Toilet ov Hell

This review DOES NOT contain spoilers. In fact, I hope it helps you better understand the chaos that is Inherent Vice.

Have you ever felt like some piece of entertainment was made just for you? As someone who enjoys things that bore or confuse most other people (I am sure many of you can relate), I was shocked when I heard two of my niche obsessions were coming together to make something that would have a wide release: Thomas Pynchon, a master of postmodern literature, and Paul Thomas Anderson, a master of torturously beautiful filmmaking.

In general, adapting novels for the big screen is a huge risk when the author has such a dedicated following. I, for one, despise the “book is better than the movie” conversation. They are such different mediums I prefer not to compare the two. With movies based on books, I tend to disregard the story when I am judging the movie. The filmmaker neither loses or gains points in regards to how closely they follow the story, or even if the story is interesting. Instead, the film earns its merits by how well it is able to make that story visually interesting. For example, books can take the time to explain the minutia of the impossibility of certain resolutions, while a dialog-based scene in a movie doing the same thing would be as unnatural as the de-masked villain explaining his evil plan as he is dragged away by the police. The filmmaker has to be able to give the full story without an “explanation scene.”

Of course the book will explain everything better than the film can, but what can make a film adaptation great is its ability to chop the script, leaving only what is necessary for the story and what the story represents. As someone who has read Inherent Vice multiple times, I can confidently say that Paul Thomas Anderson absolutely perfected the adaptation. Not only is the core of the story intact, he also managed to extract the slightly hazy, challenging essence of the prose. At this point I want to talk about how he managed to represent challenging prose in a visual medium, but I still have no idea how he did it. Although Inherent Vice is easier to follow than Pynchon’s masterpiece, Gravity’s Rainbow, it is still a story that demands your attention, as does the film.

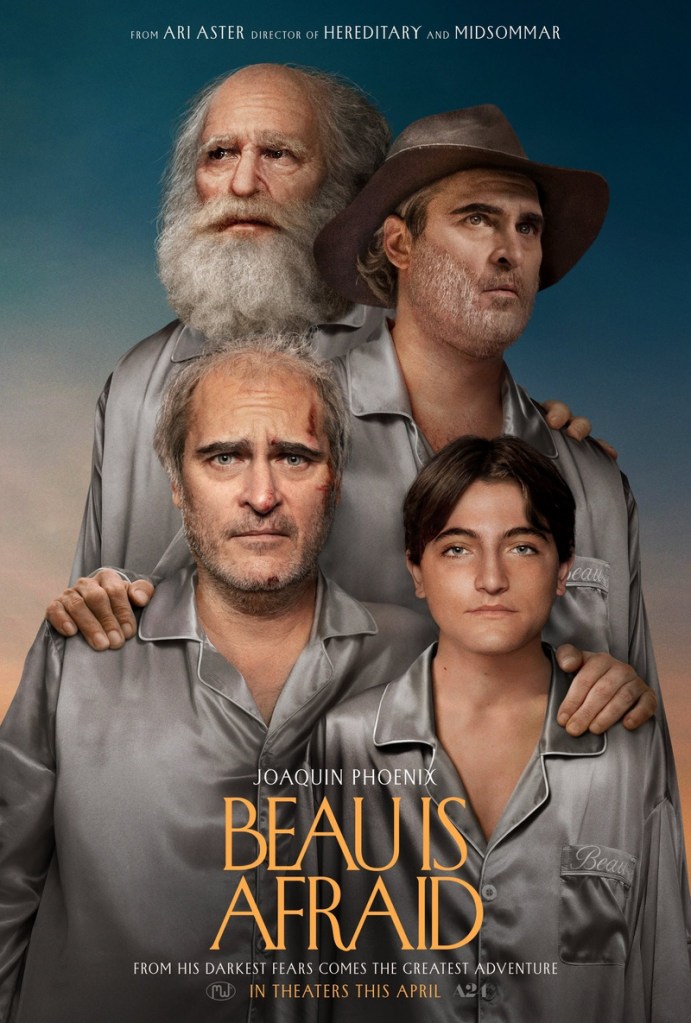

I can imagine seeing the film without any pretext will turn many off. Recent reviews tend to start with a confession of confusion, but all the details you need are there on the screen, you just need to focus on everything. Not only do you have to remember all the characters that appear on screen (there are many), but also characters and additional vocalized plotlines that never appear. There are plots and character paths leading in every direction, and every piece is needed to see the whole picture. Like the lead character, Larry “Doc” Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix), you have to become something of a Private Investigator, listening for clues and mapping the connections on a mental white board.

To talk about it in any detail, you need to have some concept of the major players in the story, but I promise there are no spoilers. Doc, a perfect representation of the hippy scene in 1970’s California, is a Private Investigator who is challenged by his ex-girl to check in on a plot against a wealthy real estate guru named Mickey Wolfmann, who she happens to be fucking. Doc tries to use his PI connections to get ahead of the game to stop the plot, primarily a homicide detective “Bigfoot” Bjornson (Josh Brolin).

Doc and Bigfoot have a long history of crossing paths while working on cases, and their love/hate relationship is one of the highlights of the novel and movie. Their history provides a platform for the duo to take cheap shots at the other’s lifestyle (Doc being on the pro-drug side of the debate, and Bigfoot being a straightedge cop who has a floundering side career in Hollywood). When Doc’s ex-old lady and Wolfmann both go missing (not a spoiler), the pair take different paths, fueled by dissimilar motives, to find out what exactly, like, happened, man.

When the movie begins, you might be slightly annoyed by the narration (especially the tone of the voice).

I can’t remember the last movie I watched that had so much narration throughout, but it serves as more than just a device to explain what is happening. In almost any other movie, I would see that as a cop-out, but the complexity of the story necessitates some omniscient input that can’t be provided through dialog. Like almost every word spoken in the movie, the narration is taken nearly word for word from the novel. Pynchon is known for his mastery of prose, and it seems that Anderson didn’t want that to go unseen in the film, so he brilliantly took a side character in the novel and gave her an extra part as the narrator. When the narrator isn’t assisting with the understanding of the plot, she is reading passages from the novel that help create the aura that Pynchon intended. It’s very lofty, scattered, and unsure of reality.

One of the keys to “getting” postmodern literature in general is understanding that what the story is about, isn’t truly what it’s about. However, at the same time, it isn’t the abstract symbolism that you would get with someone like Fitzgerald (seriously guys, what does the green light represent?). The story that Inherent Vice is telling is the story of a fading culture. How often do we hear the sigh of audible nostalgia by people who experienced the 60’s? Pynchon captures the zeitgeist of an era, when the good times are coming to an end. Bigfoot, a chronic hippy-lifestyle hater, is depicted as the force coming to erode Doc and his culture’s collective buzz. At the same time, we see a land developer destroying low-income neighborhoods for cookie-cutter homes, a president with no tolerance for lax lifestyles coming to power, and a shift from recreational and mind-opening drugs to a scene built on dependence. Behind this drug-hazed detective story lies a tragedy, the death of a perfect generation (or at least that is how people like Doc [and maybe Pynchon too, if we knew anything about him] saw it).

Compared to Anderson’s last two films (The Master and There Will Be Blood), Inherent Vice has a much different feel. The previous two were so cerebral and I am still trying to find the key that unlocks their true meanings, while Inherent Vice feels more forgiving to that end. It is also more forgiving in that the humor throughout the movie is palpable, over-the-top, and beautifully satirical. Like any of his films, Inherent Vice requires an extra viewing (or reading), but the second time around will prove that the key was never hidden, if there even was one to begin with.

(Side note: I got through a whole review about Pynchon without talking about Paranoia? I should turn in my Postmodern Member’s Club Card)