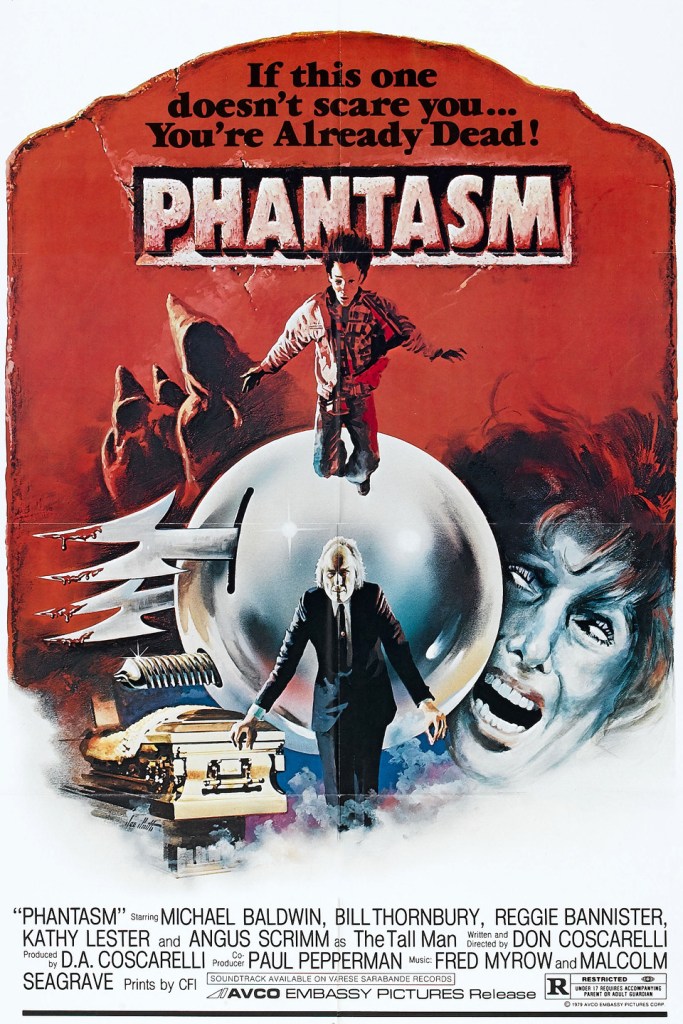

Beau Is Afraid (Film Review): A Baffling Nightmare

By Joseph Tomastik

Source: Loud and Clear

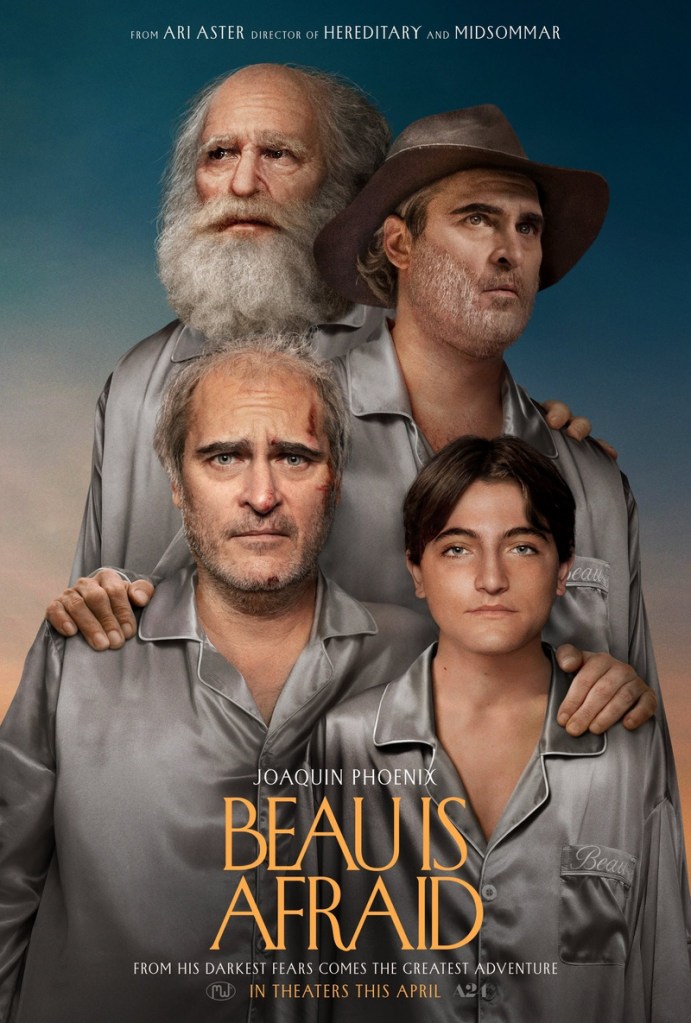

Beau is Afraid. And I’m afraid of what’s in Ari Aster’s head after watching his latest film. The director of Hereditary and Midsommar is back with Beau is Afraid, a baffling three-hour effort to make his other films look easily accessible in comparison. I love Hereditary and consider it one of the best horror films of the 2010s. I like Midsommar purely for the sensory experience of watching it, but its bare-bones, overblown story stops me from calling it good. Beau Is Afraid takes those strengths and weaknesses of Midsommar and cranks them up to eleven. And, fittingly enough, my feelings on that film are repeated twofold with this one.

Beau (Joaquin Phoenix) is an anxious man who lives in a broken-down apartment in a corrupt, violent city. He’s set to go on a trip to visit his overbearing mother (Patti LuPone), but shocking news and unfortunate events derail his trip, forcing him to cross paths with a variety of bizarre characters and surreal events. That’s as much of the plot as I’ll be revealing. Not just to avoid spoiling any surprises, but also because that’s about all I feel I’m even capable of saying. Outside of Beau being tended to along his way by a seemingly caring couple (Amy Ryan and Nathan Lane), the events of Beau is Afraid are increasingly difficult to properly wrap one’s head around.

Beau is Afraid is the kind of film that I’ve become more open to over the years. I once had the impulse to dislike any film that I didn’t instantly understand, but now I can appreciate the experience of such a baffling film if I find myself sucked into the craft, performances, visuals, or overall feel. Beau is Afraid is an unshakable 10/10 in all of those aspects. This is Aster’s most skillfully shot, visually haunting film to date. He has such an insanely perfect grasp on his directorial style that I struggle to comprehend how any human being could bring some of this film’s beauty to reality. That sounds hyperbolic, but I really was that mesmerized by what was accomplished here.

There’s so much detail in almost every single shot that you could blink and potentially miss a jarring detail. This is not only impressive, but it guarantees that no matter where or when you look, some form of misery is happening. This is especially true early on when we see what kind of environment Beau lives in. It looks like your typical city, but it feels downright alien because of how relentlessly cruel everyone is and how well the nightmare of such a place is captured. The entirety of Beau is Afraid feels like a nightmare, in fact. The are sights, sounds, and ideas are like something straight out of a David Lynch movie, and they’re never going to leave my head. And, as is typical of Aster, the whole film is effectively raw and relentlessly unpleasant. Even if you don’t always understand what’s happening or why, you feel it.

The editing emphasizes that nightmarish feel as well, not letting you skip out on a single second of the discomfort that would exist in these scenarios. There are no loud tactics or cheap jump scares here, as every dark reveal is slowly thrust upon you. The editing also gets morbidly funny. Beau is about to take a bath, he gets bad news, and a match cut shows the water spilling out onto to the floor, showing how long he’s been standing there stunned. The blocking of characters from wide shots gives so many of them the physical presence of a creeping demon, even if you don’t always know why you’re afraid of them, and the lighting outlines so many set pieces and characters in a disarming otherworldly void.

The actors are all spectacular. Phoenix is amazing as always, getting across Beau’s frightened vulnerability, uncertainty, and buried anger in a heartbreakingly sympathetic way, especially when it’s met with so much hostility. Everyone else works so well with the material they’re given. Their lines get so excessively cruel and heightened that they could easily come across as inauthentic, but every performance brings enough painfully realistic conviction to sell them.

There’s also a sequence at the center of Beau is Afraid involving a stage play that tells its own little story. This entire stretch is stunning enough to work as its own Oscar-worthy short film. It combines a variety of styles and artistry and works them into the emotion of the story being told. If other filmmakers take away anything from Beau is Afraid, it should be how innovative they can get with their own storytelling. Aster’s recurring cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski needs to become one of the most sought-after people in his field. I’m really doing very little justice in describing what he does here.

If only that play sequence felt like it mattered in the grand scheme of things. Which leads me to where Beau is Afraid falls short: the story. I don’t know whether to classify this movie as ridiculously simple or excessively convoluted, because its story is a very long, winding road to what feels like a very basic destination. Beau is Afraid is, above all else, meant to be about a man dealing with the damage his overprotective, abuse mother inflicted onto him, and how that’s molded his paranoia and anxiety. But additionally, you’re also supposed to be trying to figure out the nature of Beau’s reality. Yet the more I think about it (without the luxury of a rewatch, I must stress), the more the story and structure begin to fall apart.

A lot of this has to do with character motivations. Beau’s are fine and understandable, but everyone else makes so many nonsensical and sporadic decisions that don’t feel baked into the well-established natures of who they are. They feel like excuses to show upsetting content or move us to the next set piece. The couple that takes care of Beau has a daughter (Kylie Rogers) who believes Beau is replacing her … and I have no idea why that is, let alone why it drives her to the drastic actions she takes. They have a veteran son (Denis Ménochet) with a severe but pointless and almost tastelessly portrayed mental illness. The parents’ outlook on Beau also eventually flips in a way that feels almost pointless in the grand scheme of things.

The play I brought up initially seems like it may connect somehow to Beau’s past, present, and future, but it really doesn’t. A character supposedly from his past soon shows up, and there are no hints as to how he got there, what he’s been doing, or even what he’s even trying to accomplish, especially after another reveal later on. Flashbacks to Beau’s childhood see him interacting with a very deranged girl whose unnatural, almost sociopathic dialogue is seemingly written that way just to be weird and off-putting.

I think I know the very, very basic nature of what’s going on … maybe. The ending and the hints of said ending definitely lead me down one road, along with a few other theories that may hold some weight when I factor in my own interpretations of other reveals. But that road still leaves a lot of other threads and sequences failing to click into place, at least in a way that contributes to whatever Aster is going for thematically … I think? I swear, there’s something here that could potentially justify a lot of what I’m unclear on. I can’t say specifically what that is, but I’m hesitant to just dismiss the whole story entirely.

By the time the ending rolls around, you understand the core of what Beau is Afraid is supposed to be about. It just stretches what little meat that core has to such an absurd degree, throwing in all kinds of self-indulgent hurdles that distract from the point of the film more than they add to it. I get that certain films are supposed to not follow conventional, natural logic. But they should still have some method to their madness. Beau is Afraid goes all over the place. It’s a few minutes short of being three hours long, and that length is partially due to the many non sequiturs and needless details that muddy up the ambiguous information that probably is relevant to the bigger picture.

To the film’s credit, I never once felt that length, I was never bored, and I never wanted the glacial pacing to speed up. I also, despite how little I can grasp the film’s intentions, still find myself feeling more positively about Beau is Afraid than negatively. I think I’ll even watch it again just to relive this astonishingly constructed fever dream. I must stress that my enjoyment is almost only due to the visceral experience of the entire nightmare playing out, and not from the meaning behind it. Ari Aster is becoming a frustrating director for me because he clearly has god-tier levels of talent behind the camera. But that talent seems to lose its focus when he’s writing, a problem he’s so far only avoided with Hereditary.

I’ll give full props to A24: they clearly don’t care whether or not all of their films make money. There’s no way in my mind they could have looked at this script with this running time and thought it was going to do well. This is the kind of film that’s destined to get a C or D grade on Cinemascore and leave many audiences at odds with the general critical praise the film is getting. In that regard, if you can see yourself enjoying a film for the same reasons I enjoyed Beau is Afraid, then you should absolutely give it a shot in theaters. The same applies if you just like weird, trippy, dark films regardless of their substance. I’m still going to see Aster’s next film, because everything he’s made has shown him to be on another level of directing. He’s one of the few filmmakers who can win me over solelywith his craft, even when his stories are lacking. I just hope he eventually regains control of that crucial other half.

____________________

Watch Beau is Afraid on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/movie/beau-is-afraid-joaquin-phoenix/16497118