Category Archives: Video

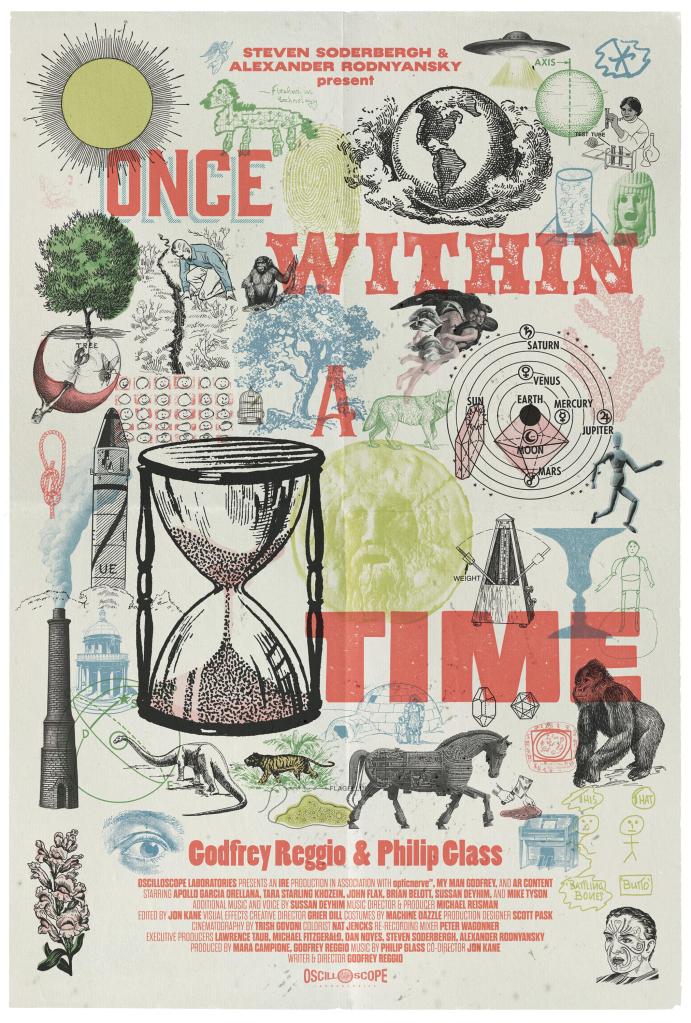

Saturday Matinee: Once Within a Time

By Sheila O’Malley

Source: RogerEbert.com

Beatrice Loayza’s fascinating New York Times article “When Did the Plot Become the Only Way to Judge a Movie?” examines films that eschew linear storytelling, films more interested in mood and emotional tones than plot points, breaking free from the “tyranny of story.” The article was fresh in my mind when I watched Godfrey Reggio’s whimsical-terrifying doomsday-fable “Once Within a Time.” Clocking in at 51 minutes, the film is all mood, all rhythm, with a kaleidoscope structure and undulating ever-shifting visuals in a constant state of flux. It’s not a “story” so much as a tone-poem collage about technology, knowledge, innocence/experience, and the potential end of the world. Maybe something new will be born from the ashes, although considering the evidence that something may very well be a monster.

It all started in the Garden of Eden, when curious Eve ate the apple, and “Once Within a Time” starts there, too, in the gentle framing device that opens it. An audience sits in a darkened theatre, a red velvet curtain rises, and the “show”—i.e., human life on the spinning planet—begins. Adam and Eve, holding hands, wander underneath a white cotton-ball tree with red hanging apples. Around them, children play and cavort. The same six or seven children are used throughout: we get to know their faces and their expressions. Behind them, a grand visual drama unfolds, made up of stop-motion animation figures, real humans, found footage, and eerie created images: solar systems, a giant hourglass in the desert, black and white newsreel footage of bomb blasts, spindly trees bending backward. The children look on with wonder, humor, interest, and sometimes concern. They are trying to understand. The apple is a portal to another world, another time. The apple is also directly linked to another 20th-century apple, the Mac apple. The garden path Adam and Eve walk down is made up of iPhone cobble stones. The meaning is obvious.

Technology is a blessing and a curse, yes, but more than that, it’s inevitable. It can’t be stopped. Nineteen-year-old Mary Shelley wrote one of the most prescient books of all time, her imagination stretching forward 200 years, its warning message still and always relevant. The obsessed maniac Frankenstein doesn’t know when to stop with his experiment. He has to see it through, even if it destroys his mind, his life, and the world as we know it. Mary Shelley saw it all. “Once Within a Time” has almost as bleak an outlook.

Reggio’s celebrated “Koyaanisqatsi,” the first of the Qatsi Trilogy, features a similar cascade of images placed in fluid shifting juxtaposition: power plants and rain forests, rush-hour highways and crashing ocean, pollution and clouds, modernity and its ruins. The images are often beautiful, but the overall effect is anxiety-provoking, sometimes even despairing. What have we done to our beautiful world? Music holds it all together. Philip Glass composed the main score, with additional music by Iranian composer Sussan Deyhim (who also plays a “muse” type character, half-woman, half-tree).

Reggio’s vision has three central figures, symbolic and archetypal, but with shifting meanings. An opera maestro declaims his incomprehensible song to the masses, his figure a towering monolith, his eyes wild and fanatical. Behind him looms the walls of a Coliseum, and his figure is threatening, a demi-god dictator, gesturing and bending the masses to his will. There’s a female figure, a living half-human Yggdrasill (Sussan Deyhim), whose song helps create—or at least sustain—the living world. In the final segment, a “mentor” appears (Mike Tyson, of all people!), who encourages the cowed lost children, acting as a sort of Pied Piper.

Once you leave Eden, of course, you can’t get back in. That’s the deal. At the end of the film, a question is asked in multiple languages: “Which age is this: the sunset or the dawn?” In the atom-bomb-haunted “Rebel Without a Cause,” Plato (Sal Mineo) asks Jim (James Dean) if he thinks the end of the world will come at night. Jim says, “No. At dawn.” Either way, it’s the end.

Watch Once Within a Time on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/movie/once-within-a-time-mike-tyson/17458850

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: The Legend of the Stardust Brothers

The Legend of The Stardust Brothers (1985) review.

By P-J Van Haecke

Source: Psycho Cinema

Introduction

In 1985, the young Makoto Tezuka, son of manga godfather Osamu Tezuka, was approached by the famous musician and tv-personality Haruo Chicada with the question to make a movie for the soundtrack he had created for a non-existing movie. Makoto Tezuka, which by then had already directed various experimental narratives, accepted and directed what would become his feature-debut narrative.

Review

One day, Kan (Kan Takagi) and Shingo (Shingo Kubota), both singers of rival bands and both vying for fame and popularity, are given an invitation by a representative of the president of the talent agency Atomic Promotion, Minami (Kiyohiko Ozaki).

The following day, having arrived at the agency, they meet the innocent and charming Marimo (Kyoto Togawa), a girl who has, driven by her desire to force an audition with the president, been caught trespassing several times. Ultimately, in order to make Kan and Shingo agree to Minami’s proposal,she gives up her desire to become a singer, instead settling for a role as president of their fan-club. But as Kan and Shingo become stars, the will soon learn that fame always comes with nasty side effects.

The Legend of the Stardust Brothers is not just another over-the-top narrative about fame and the side-effects that often go together with fame, e.g. jealousy and addiction. The Legend of the Stardust Brothers – and this is amazing – still manages, even though the narrative is envisioned as pure entertainment, to evoke (intended or unintended) a political message against uniformity (Narra-note 1). This message, which might be more relevant today than at the time of this narrative’s release, is specifically important for Japan as such, as the concept of harmony still dictates much of the social fabric. One can formulate the ultimate message of the narrative as follows: In order to combat the political forces focused on disciplining society into uniformity and obedience, diversity and the freedom of expression – subjectivity as such – are our only weapons.

The Legend of Stardust Brothers – see the visuals framing Minami’s first song – also criticizes the system of agencies as well as the blind desire for fame that drives many young people. Besides evoking the problematic power agencies have – a problem persisting up until this day – it also underlines the naivety of people who willingly give up their own agency, their own right to decide. Last but not least, The Legend of The Stardust Brothers questions the often problematic connection between mass media and politics, i.e. media as the mouthpiece of politics, entertainment as crowd-control and political influence.

The Legend of The Stardust Brothers truly deserves the signifier ‘legend’. While the main narrative thread may very well be an approximation of “what truly happened” – as is implied by the very end – the framed and presented narrative is nothing other than the exaggerated and at some times rather absurd version of Shingo and Kan. This absurdity at the level of the narrative is supported by cinematographical absurdity and the energy to be found at the level of the acting performances.

The cinematographical ‘absurdity’ is especially sensible at the level of the effects. While the various cheap special-effects betray the limitations of the budget ‐ and may even cause some frowns – these effects have after 33 years also attained a certain charm. We would even say that the cheapness of various effects help emphasizing the craziness and absurdity of the narrative as such. But these so-called cheap effects should not detract the spectator from those effects that blend fluently into the narrative fabric, e.g. the colour divide in the opening song, the fun practical horror effects, the animation sequence, and the instances of stop-motion. As a matter of fact, it has to be applauded that Makoto Tezuka, in full knowledge of the limitations of his budget, realized, in a rather bold fashion, his cinematographical vision without much compromise.

In Makoto’s framing, it is very easy to realize that, at various instances in the narrative, visual composition took preference over cinematographical continuity. In the catchy opening song, there are some compositional choices – choices deliberately braking the continuity – that have no other effect than heighten the fun. In other words, they function successfully as tongue-in-the-cheek visual puns.Furthermore, many of the visual effects – the effects we mentioned above – applied in the later narrative can be seen in the same way, as visual elements focused on fun.

There is a certain youthful energy that supports the entire narrative, an energy that emanates from Shingo Kubota and Kan Takagi and – as mentioned before – gets empowered by the bold way the narrative is framed as such. It is especially this energy, paired with those moments of charming comedic over-acting – over-acting often function of the amateurism of the concerned actors (see for instance Kiyohiko Ozaki’s performance) – that turn The Legend Of The Stardust Brothers into a 100 minutes long crazy roller-coaster of fun and musical entertainment.

The music of The Legend Of The Stardust Brothers is utterly fantastic. Besides creating the fun eighties vibe that persists throughout the narrative, the infectious songs allow the spectator to enjoy a wide range of genres popular in the eighties. It is also evident that the music genres have also dictated the performances as such – ISSAY’s performance for instance brings the style of David Bowie wonderfully to live.

The Legend of the Stardust Brothers is one of those rare narratives that has become better by aging, instead of turning ugly and sour. While the ripeness of the narrative is not able to beautify all its faults, the pure fun oozing from the narrative and the performances secures the enjoyment the spectator can extract from this energetic and truly irresistible legend. In other words, the time for this narrative to become, thanks to the release of the DVD/Blu-ray by Third Windows Films, a cult-classic has finally arrived.

Narra-note 1: This concerns the revelation of Kaoru’s father. For more information, one can read our exclusive report of our meeting with Makoto Tezuka.

Watch The Legend of the Stardust Brothers on Hoopla here: https://www.hoopladigital.com/movie/the-legend-of-the-stardust-brothers-shingo-kubota/17400468

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: The Elephant Man

RIP David Lynch (January 20, 1946 – January 16, 2025)

The Elephant Man (1980) is not often considered one of David Lynch’s masterpieces, though it’s one of his most critically acclaimed films, having been nominated for eight Academy Awards and winning a BAFTA Award for Best Film. It also happens to be a film of great personal significance because it was my first David Lynch film experience.

Though only six, I still remember seeing a daytime screening with my mom and being disturbed yet fascinated by the stark black and white imagery and lead character (played by John Hurt and loosely based on Joseph Merrick). Though I may have been too young to follow the plot, the film’s emotional journey and compassionate message left a lasting impression.

Two for Tuesday

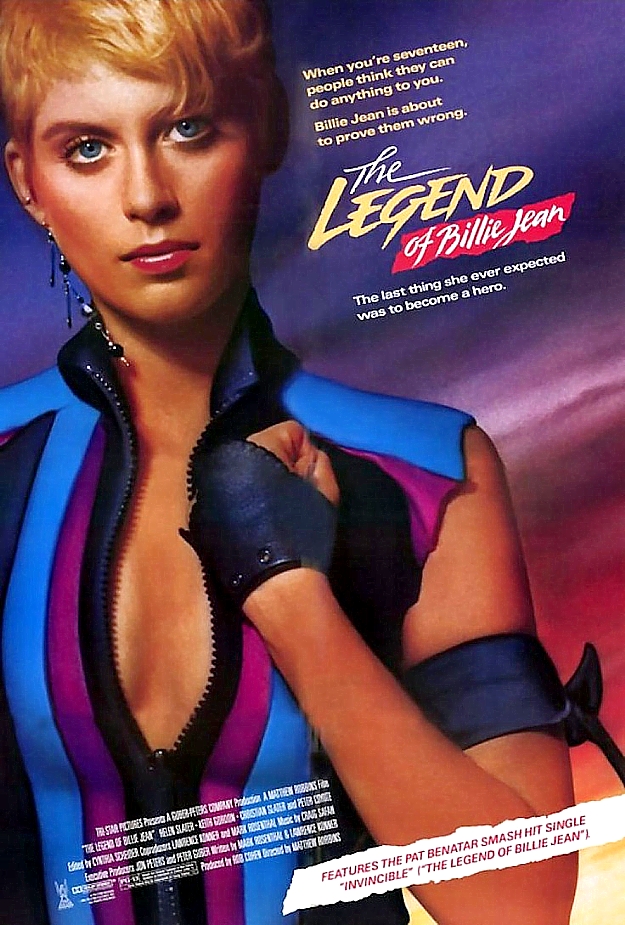

Saturday Matinee: The Legend Of Billie Jean

What Went Right With… The Legend Of Billie Jean (1985)?

By WWRW

Source: What Went Right With

The 1980s were a crap time for politics and economics but in terms of entertainment, the decade was responsible for some great movies, especially those geared toward kids and teens. Most ’80s movies like Back To The Future and Breakfast Club are well known, then there’s the second-tier which includes not-so-famous-but-still-recognisable stuff such as Flight Of The Navigator and WarGames. But then there’s the section below that; films that have now become cult classics because the mainstream were either unaware or too snobbish to watch them when they were first released. The Legend Of Billie Jean is one of these forgotten gems; it has nothing to do with the classic Michael Jackson song, but it’s a fantastic teen film that’s unfortunately underexposed and underrated, even to this day. Starring Helen Slater (Secret Of My Success, Ruthless People) and an early role for Christian Slater (Heathers, Young Guns) (no relation by the way) the story is about sister and brother Billie Jean Davy and Binx Davy played by Helen and Christian respectively. After Binx’ beloved Honda Elite scooter is vandalised by local bullies, Jean asks the alpha bully’s father for $608 to repair it. It seems however, that being a prick runs in their family as the dad, Mr. Pyatt, will only hand over the money in exchange for sexual favours, which of course leads to refusal, and ends in an unintended shooting. Billie Jean, Binx, and her two friends then have to go on the run but infamy and fame go hand-in-hand with being an outlaw…

The Legend Of Billie Jean is all about how role models and heroes are made. Like Alex Rogan in The Last Starfighter, Billie Jean lives in a trailer park and isn’t someone who anyone would look up to. But, as she stands-up for what’s right and becomes a fugitive in the process, she becomes an inspiration to all teenagers and is even helped by them to evade the cops. Billie Jean is asked to autograph a newspaper, her Joan Of Arc-inspired haircut is copied by local teens and her image is adorned on t-shirts, caps, posters, frisbees, bumper stickers, and even airplane banners as she becomes the “legend” in the title. You could see this as a comment on how consumerism and capitalism is an unavoidable by-product of causes and activism, but that’s not the message here. This film is a precursor to the overrated Queen & Slim whose narrative essentially did the same thing but stereotypically and depressingly rather than upbeat and uplifting as is the case here. Unlike Queen & Slim, The Legend Of Billie Jean doesn’t just focus on the original “crime”. Whilst on her Texan Riviera outlaw odyssey, Billie Jean rescues a kid from his abusive father, and thus becomes a genuine hero akin to Supergirl.

Set in the height of summer in Corpus Christi, Texas, the cinematography isn’t Do The Right Thing (which made relatively cold days look blisteringly hot) and the direction isn’t something that stands-out either (although there’s a Larry Cohen-esque interviewing of what looks like real people in “Ocean Park Mall”). That being said, the look and feel is appropriate to the setting and the target audience. In terms of cast, Helen Slater is great as the principled lead character and her friends are an oddball mixture which includes Yeardly Smith (Maximum Overdrive) who most people will know as the voice of Lisa in The Simpsons. Richard Bradford is particularly believable as the rapey Mr. Pyatt who then sets-up a stall to sell Billie Jean merch, and the always likeable Peter Coyote plays the cop who isn’t just out for blood but the one bloke who’s looking to discover what really happened. Keith Gordon (Dressed To Kill, Christine) also plays a pre-Pretty In Pink love interest across the class divide.

Being an ’80s teen movie, there’s the obligatory mall scene (the fictional Ocean Park Mall is shot in Sunrise Mall in Corpus Christi which is sadly now closed), our protagonists somehow use toy walkie-talkies long-range, and there’s inept cops chasing but never catching our heroes. In terms of soundtrack, this isn’t a John Hughes movie so the music is a little bit ropey and too “old” for the intended target audience (Pat Benatar instead of Simple Minds) but that being said, now that almost four decades have passed, even crappy pop music of the day sounds tolerable.

The Legend Of Billie Jean has an unrealistic and idealist narrative; it’s a feel-good adventure rather than a depressing drama. It could also be seen as a Feminist film whether it was originally intended to be or not. Like a reverse of The Goonies or Stranger Things, the girls outnumber the boys here. With the female lead sticking-up for her brother as well and fighting against a male sexual assaulter, plus a screenplay that isn’t shy about menstruation, if it was made today, critics would be slobbering over it as it ticks all their boxes in regards to female empowerment. That being said, on Rotten Tomatoes, The Legend Of Billie Jean is rated at 40% which makes it sound like a sub-par, throwaway flick which it quite clearly isn’t. I think mainstream critics need their heads testing or need to recognise that their reviews were wrong. After all…

Fair Is Fair.