Category Archives: culture

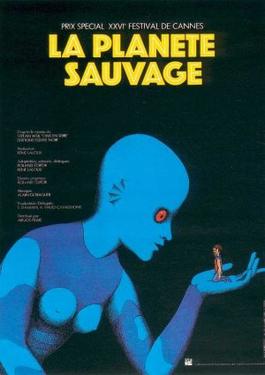

Saturday Matinee: Fantastic Planet

Surrealism and political critique in the animated medium: Fantastic Planet (1973)

By Dan Stalcup

Source: The Goods Firm Reviews

Coming from the “Panic Movement” surrealist art collective is one of the most bizarre animated films of all time: Fantastic Planet, a French-Czech production by director/co-writer René Laloux and co-writer/production designer Roland Topor.

With its title, Fantastic Planet sounds like it should be a cheesy sci-fi flick, and in some ways, it is. (The French title, La Planète sauvage, is much more pleasing.) But this is something much more insular and experimental than most genre films of the era. Thanks to its distinctive pencil-sketched, cutout animation technique (also seen in Monty Python interludes), the film has the look of a history or biology book come to life. The grotesqueries depicted have a diagrammatic, almost clinical look to them, making every alien and bit of worldbuilding feel all the more strange.

Fantastic Planet chronicles a far future when humans have been transplanted to the distant planet Ygam by giant blue aliens with red bug eyes called Draags (or, in some translations, Traags). There, humans serve the role of something resembling a rodent or small dog: occasionally domesticated by Draags, occasionally living in wild colonies as feral creatures. The humans on Ygam are called “Oms” by the Draags. They’re mostly viewed as harmless by the aliens, but often casually exploited and exterminated when convenient.

The story follows Terr, an orphaned human/Om, who is adopted by a Draag, but escapes before organizing an resistance to the giant aliens. Terr’s life has a vaguely mythological arc to it, further enhancing the sense the we’re witnessing some passed-down story. The entire telling is detached and emotionless — when Terr’s mother or compatriots die, there is no mourning or reaction, just a progression to the next item of the story. It’s disquieting.

What really makes Fantastic Planet so bizarre and unforgettable is the depiction of the alien life and planet: flora and fauna that look like something out of a fever dream or acid trip. The ground shifts into squirming intestines; a hookah bar causes the inhabitants to meld into a blur; twirling headless statues perform a mating ritual. It’s baroque and occasionally whimsical; half Dr. Seuss, half Salvador Dali.

Despite the strangeness of the imagery, the film avoids slipping into an all-out dissociated psychedelic trip thanks to its linear and straightforward narrative. This, paradoxically, makes everything feel even more alien: The story takes logical, coherent leaps, but the images and details within are so nonchalantly unearthly. It’s a dizzying juxtaposition.

The story is clearly allegorical: Animal rights is an obvious interpretation given the way that humans are chattelized. It’s not hard to squint and see anti-racism or anti-imperialism in its parable, either — any scenario where the majority or oppressors are negligent, systemic participators rather than active aggressors would fit.

There’s also a lot of coming of age imagery in the film, blown out into absurdism. The semi-comprehending way the humans perceive the Draag world is not too detached from the way kids see the adult world: full of obtuse rituals and norms. Plenty of the designs are charged with phallic and sexual imagery (not to mention casual nudity), but it’s secondary to the overall sweep of the visual invention of the film.

In the half century since its release, Fantastic Planet has become a cult legend, even inducted into the Criterion Collection — one of only a few animated films with the honor. According to Letterboxd, it’s among the most popular films of 1973. I can’t say I blame cinephiles out there. Even at 72 minutes, Fantastic Planet is a bit exhausting, but it’s such a unique and evocative experience that it is essential viewing. At least for weirdos like me.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: The History of the World Backwards

Source: Wikipedia

The History of the World Backwards is a comedy sketch show written and starring Rob Newman. It is a mock history programme set in an alternative world where time flows forwards whilst history told backwards. In other words, if you were born in 2007, you would be 60 years old in 1947. All the major historical events happen backwards, so for example, Nelson Mandela enters jail a Spice Girls fan, and comes out as a terrorist intent in overthrowing the state. There are several recurring themes, such as the “Technology collapse”, where scientific discoveries are lost, forgotten or made unworkable.

It was shown on BBC Four, starting on 30 October 2007, and later shown on BBC Two. It was Newman’s first television project in 14 years.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: Homecoming

By Michael Gingold

Source: Fangoria

Part of the appeal of Masters of Horror has been the chance to see things on this Showtime series that you won’t see anywhere else on television. So far, that has mostly meant explicit gore, nudity and sexuality, which is all fine and well. But Joe Dante’s Homecoming, premiering December 2, treats us to sights that are not only unique in the TV horror genre, but have been off-limits anywhere else on the tube as well. Like, f’rinstance, rows of flag-draped coffins bearing the bodies of dead soldiers killed in a Mideast war.

Yes, Dante is back in horror-satire mode, and this time he and screenwriter Sam Hamm (adapting the short story “Death and Suffrage” by Dale Bailey) are directly taking on a target that the rest of TV-drama-land and mainstream Hollywood has heretofore largely danced around. The result is as pointed, clever and blackly amusing as anything the genre has seen in ages, a perfect example of horror’s ability to address subjects too touchy to deal with in other genres. It also takes the political subtext of George A. Romero’s Dead series and puts it right up in the forefront, without becoming preachy with its message. Dante and Hamm manage the tricky balancing act of shining a harsh light on current events without losing sight of the fact that they’re telling a horror story first and foremost.

Hamm’s script takes place in the near future, specifically 2008, when a certain Republican president is running for re-election and a war he duped the nation into fighting still rages on. The central characters are campaign consultant David Murch (Jon Tenney) and right-wing author Jane Cleaver (Thea Gill), who has written a popular book attacking the “radical left”—any resemblance to Ann Coulter is, uh, purely coincidental. After meeting on a dead-on parody of an issues-oriented talk show (Terry David Mulligan is perfect as the host), the two find themselves politically and romantically attracted—but their world is shaken up when the dead begin returning to life. Not all the deceased, mind you, just those who were killed in that particular overseas combat, and they’ve got a particular—pardon the pun—ax to grind. It’s an extrapolation of the Vietnam-era ghoul film Deathdream to the nth degree—the image of the first revived corpse pushing its way out from under the Stars and Stripes that cover its casket is the most pointed and arresting image the genre has recently offered.

No more should be said about the plot particulars of Homecoming, which is packed with wonderful details and images; given a document to read, a zombie missing an eye puts on a pair of glasses with a shot-out lens. The way in which Dante and Hamm keep the story twists coming, never losing steam or running in place thematically or dramatically, is kind of breathtaking; every scene has a revelation or line of dialogue that adds new dimension to either the story or the satire. The actors (also including Dante regular Robert Picardo as a political advisor with a secret of his own) adopt just the right tone of straight-faced earnestness, selling every line and never winking at the camera. The behind-the-scenes craftspeople do a good job of substituting Vancouver locations for the D.C. area (this is also the most expansive-looking Masters yet), and Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger contribute undead makeups that get the points across (like that eyeless ghoul) without being showy.

As the film goes on and we learn more about the characters (particularly Murch), Homecoming’s antiwar message gains new levels of resonance, and it comes to a stirring and completely apt conclusion that perfectly ties up the assorted story threads. And even though horror fans are the species of television viewer least likely to be conservative, you don’t get a sense of preaching to the converted here; the writing and filmmaking are so sharp, even some red-staters might respond to the material. For the second year in a row, a satirical zombie project stacks up as the year’s best horror production; here’s hoping someone in Hollywood notices, and gives Dante a shot at a feature that will show off the skills that, on this evidence, are only becoming sharper with time.

Two for Tuesday

Saturday Matinee: La Haine

La Haine: So Far, So Good

By Ana Saplala

Source: Medium

With Les Miserables signalling Ladj Ly’s rise to recognition in contemporary French cinema, one simply cannot watch the director’s debut film without bringing to mind its predecessor — a film that not only broadened its examination of racial tensions in France, but would come (and continue to) define the country’s prevalence with race relations to this day.

La Haine is the film in question, as Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 debut became a nationwide success. The dialectics of Ladj Ly’s Cesar win for Best Film reflect this, given that Kassovitz achieved the same feat 25 years prior. The result would not only cement his debut in film history, but further accentuate the undoubted declaration of La Haine as one of the most prolific French films of all time.

While clearly drawing inspiration from the likes of Ernest Dickerson and Spike Lee, La Haine remains difficult to categorize, but also inseparable from its influences. This is due to Kassovitz’s work being deeply ingrained with its own share of sociopolitical messages, whose prevalence with current events keeps it closely linked to any discourse related to the film.

Unlike films of a similar nature, specifically Do The Right Thing, La Haine does not attempt to intertwine the stories of humans who function as several moving parts of Parisian banlieue (suburbs) as a whole. Rather, it focuses on Vinz (Vincent Cassel), Said (Said Taghmaoui), and Hubert (Hubert Kounde), three adolescent boys and residents of said setting who go about their day. Because of its near abandonment of plot, the film initially presents itself as a reflective lamenting of grievance. The actuality of Abdel’s death opens and looms over the majority of the film, quickly becoming the driving force of its characters’ intentions.

The lines between cause and effect constantly blur from one vignette to the next, as the film’s plot slowly races to its unexpected finishing crescendo, or should I say derescendo, given that the film’s actual standstill does not even come in the form of its mostly mundane happenings. Despite this, these happenings still manage to show us more than several glimpses of life in the banlieues. In fact, the only difference between the film’s depiction of police reinforcement to the present day is a jarring increase in police hostility (first shown in Wesh Wesh, Qu’est-ce qui c’est passe?, then rehashed in Les Mis).

As a result, the film’s plot moves towards its ending with no checkpoints in between. Its brilliant performances are briefly forgotten once the banlieues’ cultural equilibrium (despite the actual absence of unity due to class circumstance and police presence) is shattered. With this in mind, the best way to describe the chronicling of these events is as follows: the build-up doesn’t matter as much as the result itself.

Another element that this film brilliantly uses in executing a correlation between plot and character development is tension. Its simplistic premise is cemented in both the value of time and the counterproductive reality of choosing violence. Time punctures all minor wounds caused by each subsequent event, putting each character at a risk of surviving a long and winding evening — but especially Vinz.

Time’s transformative effect on La Haine’s scenes instills the stagnance of progression, as well as giving urgency to Vinz’s constantly violent tendencies in the midst of composing events. It can be likened to Tupac’s Bishop from Ernest Dickerson’s Juice, given that their intentions appear to be inherently violent and remain impassioned within violence as an objective solution. This projects their idea of violence as an act of reclaiming power and restoring justice. However, as a result of time being an all-encompassing element of the film, it poses the potential for these tendencies to seep into reality at any given moment.

The film manages a passage of time with the simple use of timestamps and the sound of a ticking clock, indicating that time is like a ticking bomb that only continues to pass with each inconsequential event. Oftentimes, we believe that time has run out whenever characters face consequences in this film, but it only adds to the fact that time can do no more than elapse. Time seems to stop when Said is arrested, but it continues even when he is released. Time seems to stop when Vinz begins seeing visions of a cow, but it continues even when Said pulls him away. They further accentuate the meaninglessness of scenes, dismissing the possibility of characters working against the worst imaginable circumstance, and ultimately coming to the somber realization that all these three boys have been doing was waste time.

An undoubtedly significant theme of this film is centered on cultural identity, given that three of France’s most marginalized backgrounds (Black, Jewish, and Arab) are represented through its trio of individual characters. Because France’s white predominance does not vindicate those groups as authentic representations of national identity, this manages to cause the most friction amongst two separate parts of French society. This also includes visible minorities in positions of authority serving to practically betray the safety of their own culture.

Much like housing projects in major American cities like New York, the culture of les banlieues is also in alignment with what isn’t considered as pure French. As a part of showcasing insignificant events, there remains the background significance of the banlieues’ cultural mosaic; a true passport to surroundings that are more otherworldly and intersectional than the iconoclastic capital housing the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre. This leaves a profound impact on the characters’ conversations and language, both of which only continue to return to a means of getting by. An emerging French identity is formed in front of us, and this fusion of cultures can be largely attested to its use of hip-hop music and its incorporation of hip-hop culture.

Hip-hop’s significance is especially given its due and proof on an international scale, and La Haine is this American genre’s earliest example. This is also proof of the benefit of arguing that a musical genre and culture made by and for minority communities is the most universal of its kind. To add onto this, the globalization of hip-hop would truly come to fruition by the late 90s, and France’s scene would eventually receive recognition through the likes of Assassin and Supreme NTM. No genre remains more fitting for Kassovitz’s debut, as these groups also share inherently sociopolitical themes within their music.

It comes as no surprise either that La Haine’s influence is inherently American despite still being ingrained in French culture. The likes of Brian de Palma, Gordon Parks, and Martin Scorsese also come to mind, given that New Hollywood cinema seems to stay more true to the middle-to-lower-class French experience than the works of Robert Bresson, Claude Sautet, and Francois Truffaut.

Perhaps the only exceptions to the rule would be the forerunners of the 80s cinema du look, whose stylistic influences also extended to American cinema. Then again, only a select few in les banlieues could truly relate to a Subway, or a Diva, or a Mauvais Sang. These filmic fantasies still remain largely out of reach to the experiences of those living on the fringes of the era’s sprawling city settings.

La Haine comfortably splits its plot in two, shifting from suburban homeliness to the uncanny city. This is also why the film’s second half reflects the indiscernible identity of Parisian life, which only seems to take on many faces (and phases) on screen. Here, Kassovitz shows Paris as bare and devoid of the ethnic intersectionalism of its suburban outskirts. There’s an increasing sense of discomfort once these characters step out of a melting pot and into a homogenous place of lifelessness. Paris’s identity is as conflicted as its hesitance to embrace its characters. One scene shows the trio loitering at an exhibit, only for its highbrow bourgeoisie to oust them from a gallery. Its reality only contradicts the seemingly welcoming feeling that defines Paris as a cityscape and hegemonic extension of movie magic.

Overall, La Haine does not merely grieve over the disturbing normalcy of police brutality, but stands as a grievance of French society’s oppression towards its increasingly minority population. Its end result is an eruption to the most gradual anticipation that dominates the film, and it proves that the most profound influence on our identities lies within our surroundings. Its loss of control does not happen through an individually caused circumstance, but the reaction of an external force towards its inhabitants that becomes the film’s penultimate decision, its ultimatum literally shrouded in the ambiguity that continues to paint a sombering portrait of an unchanged reality.

Its structure continues to pose the same questions to all of French society: Who controls our own lives if we do not? And even then, is this world truly ours to begin with?

I could ask the same question of every racially counterproductive society at the moment, but especially France’s, whose innovations in film do not necessarily account for the lack thereof in every other facet of society. Where their movies are more than four miles ahead, their definition of personal and political authority remains centuries back.

Hatred begets more hatred, as Hubert says in this film, and it is one’s hatred that begets the film’s destruction of temporary unity. The beginning reemerges, and all progress is forgotten. That how you fall doesn’t matter. It’s how you land. This is what makes La Haine a cinematic masterpiece.

Watch La Haine on Kanopy here: https://www.kanopy.com/en/product/214683