By Charles Hugh Smith

Source: Of Two Minds

Does anyone really believe that the renunciation of massive, sustained stimulus of speculation in housing would leave housing valuations unchanged because valuations are solely the result of “shortages”?

Let’s begin by stipulating that speculation (i.e. gambling) is part of human nature. The role of regulations and policy is to limit the damage that gambling inevitably inflicts when “sure things” cliff-dive into losses.

In other words, where the speculative frenzy and money flows matters. When the South Sea Bubble expanded circa 1713-1720, this flood tide of speculative capital did not distort the cost of shelter and bread in England; it was limited to a purely financial marketplace of shares in the company. When the bubble imploded in 1720, the losses fell mostly on wealthy investors like Isaac Newton.

The same can be said of the speculative mania of the dot-com era: the bubble and collapse were limited to the tech sector and those participating in the sector and the speculative frenzy. The cost of rent and bread did not double due to the speculative bubble’s inflation or bursting.

In contrast, when speculation floods into shelter / housing, it fatally distorts the cost of housing non-speculators must pay. I say fatally because shelter, along with food, energy and water (the FEW resources), are essential to life. These are not discretionary things we can decide not to have. When the price of essentials soars due to speculation that only rewards the speculators at the expense of non-speculators, the fuse of social disorder is lit.

Anyone who believes policies that encourage the wealthy to hoard housing to the point that the bottom 80% (or the bottom 95% in some areas) cannot afford to buy a home are just peachy is overdosing Delusionol. The social consequences are severe and uncontainable once the worm turns.

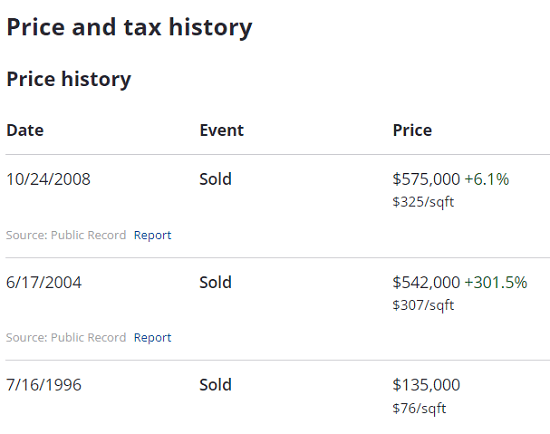

Exhibit #1 in Shelter Becoming a Speculative Asset is a modest house in the San Francisco Bay Area that sold for $135,000 in mid-1996. By modest I mean small, old, and on a small lot in a neighborhood of other small lots and homes. (A screenshot of the Zillow history is below.)

Today the home’s value is estimated to be about ten times higher: $1.35 million. Let’s do some basic math to understand just how distorted this market has become.

The median household income in 1996 was about $39,000. For a house costing $135,000, this represents 3.5 ratio of income to housing, well within the traditional ratio of 4 to 1 (4 X income = cost of the home).

Median household income has almost doubled to $75,000, roughly in line with inflation according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. According to the BLS, the house that cost $135,000 in July 1996 would now cost $264,000 when adjusted for inflation, and the $39,000 median income would be $76,000.

Let’s say the house appreciated above the rate of inflation to $300,000 today. That’s still within the 4 to 1 ratio of income to house cost (4 X $75,000 = $300,000.) So even though the house rose 2.2X in cost, it would still be affordable to a median household.

At a value of $1.35 million, a household would need to make $337,500 annually–an income that is in the top 5% of households–to buy the house today. In other words, an income that is 4.5 times the median household income is the minimum needed to buy this modest house.

The house is now worth 4.5 times what it would have been worth if it had appreciated well above inflation.

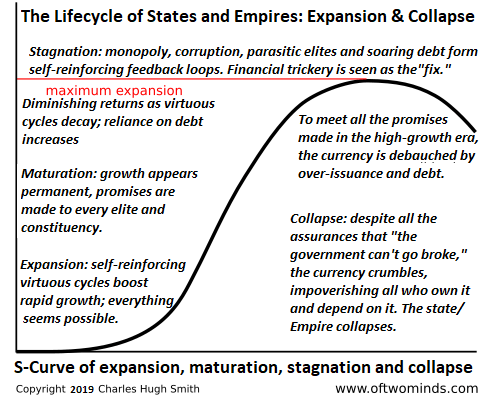

The conventional argument holds that this four-fold increase in housing costs is due solely to a shortage of housing. Let’s consider some data before concluding this is the only dynamic in play.

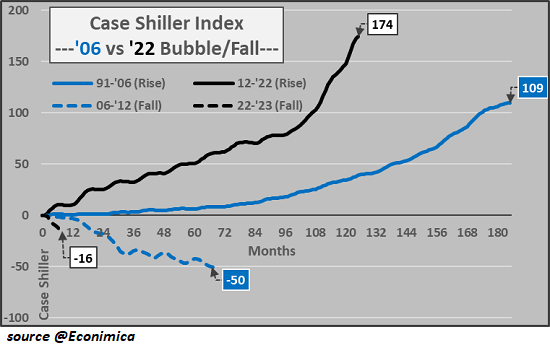

Chart #1: Case Shiller housing index: this chart shows two massive housing bubbles in the past 20 years.

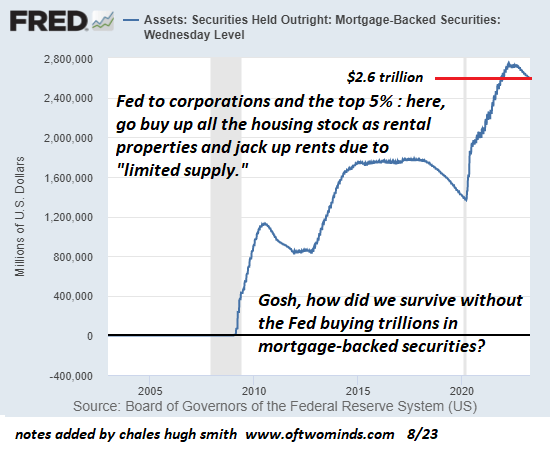

Chart #2: Federal Reserve’s purchases of mortgage backed securities (MBS) to goose the housing market. The “housing shortage” argument claims the unprecedented Fed purchases of trillions of dollars of MBS is not correlated to the housing bubble, but this claim makes no sense: dropping mortgage rates to unprecedented lows while soaking up trillions of dollars in securitized mortgages was like injecting speculative crack cocaine into the housing market. Gosh, how did we survive without the Fed buying $2.5 trillion in mortgages?

Chart #3: the current housing bubble compared to the 2000-2006 housing bubble: today’s bubble is even more extreme than housing bubble #1.

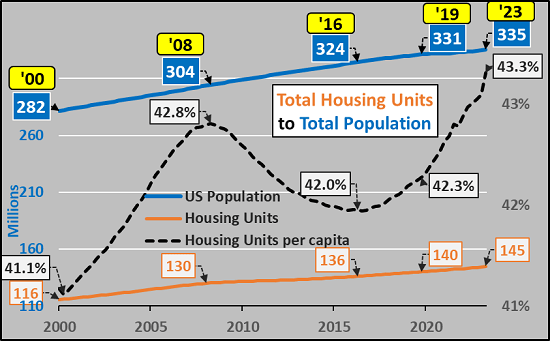

Chart #4: housing per capita (per person) has reached a new high: if there’s such a severe shortage of housing, how can the housing per capita be at an all-time high? Population rose 4 million in the past 4 years while 5 million housing units were added–plus a pig-in-a-python of housing in the pipeline.

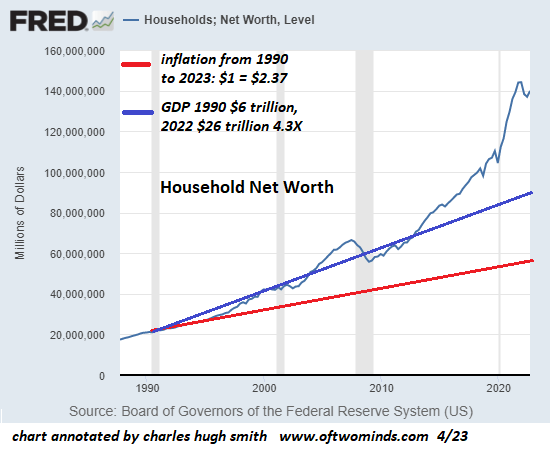

Chart #5: household net worth is $50 trillion above trend, the direct result of massive monetary and fiscal stimulus. Tens of trillions of dollars were borrowed into existence and pumped into so-called risk assets–assets such as housing that the wealthy buy for speculative appreciation.

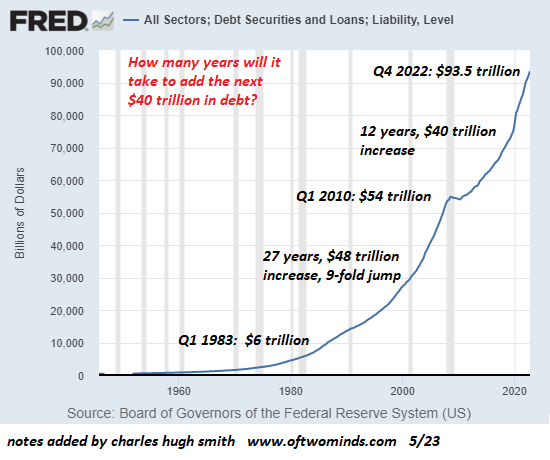

Chart #6: total debt–private and public–soared from $20 trillion in 1996 to $95 trillion now. Is it merely coincidental that this is $55 trillion above the trendline of inflation, which would have placed total debt at $40 trillion today?

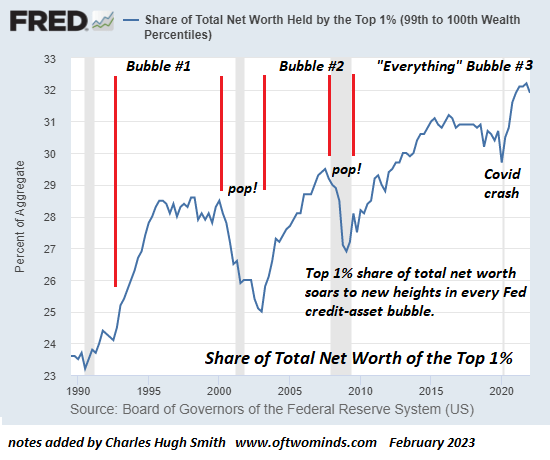

Chart #7: net worth of the top 1% households, which soared from 23% of all net worth to 32%: this 9% gain in the percentage of all household net worth represents a gain of $14 trillion above and beyond the $28.7 trillion in gains registered by the 23% they owned in 1990.

1990 total net worth: $21 trillion, 23% = $4.8 trillion; 2023 total net worth: $146 trillion, 23% = $33.5 trillion; $33.5 trillion – $4.8 trillion = $28.7 trillion.

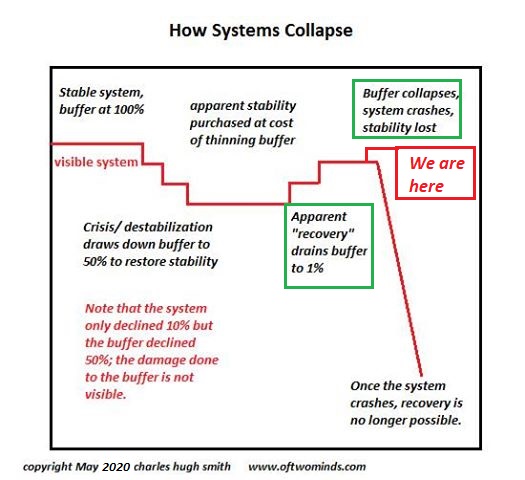

This unprecedented bubble in housing valuations is due not to shortages but to decades of massive financial stimulus that incentivized speculative capital to flood into housing as a low-risk way to skim stupendous gains for creating zero gains in productivity. If you doubt this, then run this scenario and tell us what happens:

The Fed dumps its entire portfolio of mortgage backed securities and stipulates it will never buy any again. It also renounces all the other stimulus gimmicks that incentivized expansions of debt and speculation.

Does anyone really believe that the renunciation of massive, sustained stimulus of speculation in housing would leave housing valuations unchanged because valuations are solely the result of “shortages”? If so, there’s a little shack under the Brooklyn Bridge I’ll let you have for a couple of million. I’m sure the Airbnb rent will mint you millions.